Step 1: Work Out How Many Ships You'll Need

You need to ferry an army of over 7,000 men across the Channel, with their armour, weapons, horses and supplies - how will you do it?

We don't know for sure how many ships there were in William's fleet. One chronicler says he had 3,000. But chroniclers often exaggerated, and from more precise records the real total was probably somewhere between 700 and 800 ships.

Step 2: What Kind of Ships Will You Use?

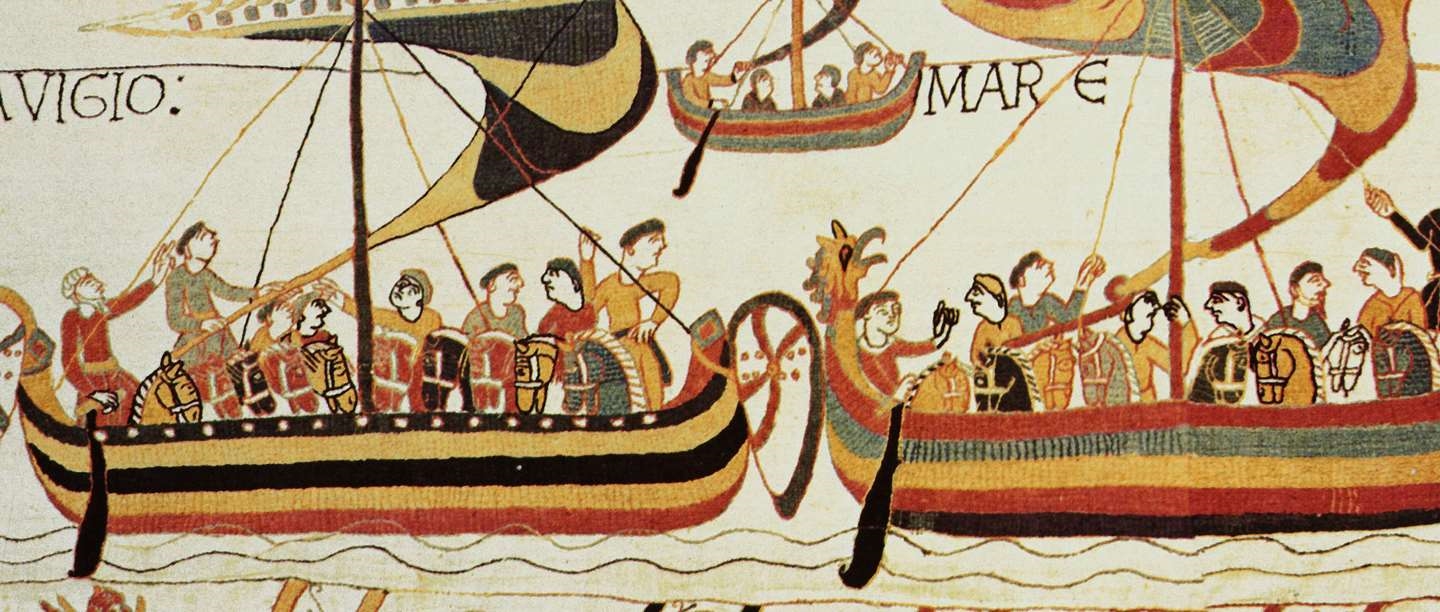

All the vessels shown in the Bayeux Tapestry are Viking-style 'longships'. The Vikings were the most successful seamen of the time, and everyone copied their designs. These ships might be 25 or more metres in length and around 5 wide, sharp at both ends, with carved dragon figureheads. They had a single mast with one big painted sail, but could also be rowed. The dots shown on the sides of Bayeux Tapestry ships are 'ports' for oars, ranging from 12 to 16 a side, though ships with many more rowers are known.

Though they're not shown on the Tapestry, William probably also used smaller, rounder ships as transports. But there aren't enough ships in Normandy for the invasion, so you must...

Step 3: Build Lots More Ships

From the spring until the late summer of 1066, the Normans build ships as fast as they can. Every great man must build his quota for the invasion, from the hundred or more ships provided by the richest barons to the single ship contributed by an abbey. William's own flagship, the 'Mora', is a present from his wife Matilda.

The Bayeux Tapestry shows how they're built. First, trees are cut down with long-handled axes. Next, the big timber frame is shaped with a short handled 'side-axe'. This is made up of the keel (and the ribs which spead out from it) and posts for the bow and stern. Piles of planks split from tree-trunks wait to be pegged or nailed to the ribs - Norman ships are 'clinker-built', with tiers of overlapping planks. In the lower ship two men with hammers nail on planks, and in the upper vessel a carpenter drills out an oar-port. Then the ships are dragged to the sea.

Step 4: Pack Your Supplies

You'll need to load everything your army will need, not only for the short voyage but also for the fighting when you land. The Bayeux Tapestry shows servants carrying mail-shirts, swords, lances and helmets being held by their nose-guards. Nobody wears heavy armour aboard ship, because if you fall in wearing it, you drown.

Others carry or haul along barrels of wine. William drank wine with his breakfast on the day of the landing. You'll also need long-lasting foods like salted bacon and beef, cheese, dried beans and hard-baked bread or biscuit. And of course you'll need water and fodder - probably oats or corn - for those very important passengers, the horses.

Step 5: Get The Horses Aboard

Mounted knights are the secret weapon of the Normans, and knights need their own horses, specially trained to carry armoured men in battle. So William's fleet carries up to 2,000 horses, shown alongside their masters in the Bayeux Tapestry. They're wearing bridles, and would be securely tethered to stop them stampeding.

Carrying horses in open ships is difficult and dangerous, and is something new in northern Europe. William's knights probably learned how to do it from Normans who'd served with the Emperors of Constantinople, whose armies often transported cavalry mounts across seas. Even so, horses don't like boats, and it's difficult to get them on and off - the Tapestry shows them being made to jump over the sides of the ships.

Step 6: Get The Soldiers Abroad

Getting the soldiers on board needs careful management. Not all of William's forces are from Normandy: there are also knights and foot-soldiers from other parts of France, especially Brittany, serving for pay or in the hope of plundering England. They don't all speak the same language. There are also lots of non-combatant servants. You'll have to stop them getting into fights, or getting in the way of the sailors trying to work the ships. So you won't get the men and horses aboard while you...

Step 7: Wait For A Favourable Wind

Your sailing ships are completely dependent on the right wind. Having only a single sail, they are much less manoeuvrable than the bigger multi-masted sailing ships which developed later. What you need to get to England is a wind from the south.

But even William couldn't command the winds. On about 12 August his fleet assembled off the River Dives, north-east of Caen, but was windbound there for a month. Then, on 12 September, a storm drove it east to St. Valéry at the mouth of the Somme, where it was stuck for another fortnight while William anxiously watched the church weathercock for a south wind. It blew at last on 27 September, and his fleet crossed the Channel during that night.

Early the next morning, 28 September 1066, the Normans landed in England at Pevensey.

You might also like