Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, was one of the most charismatic figures in Georgian society. Affectionately known as Gee, she was renowned for her style and her involvement in politics.

In 1774, at the age of 17, she married William Cavendish, the 5th Duke of Devonshire. The marriage would prove unhappy. Nevertheless, as the wife of one the richest men in the country, Georgiana could indulge her passion for fashion, introducing the vogue for elaborate and tall hairstyles. She also loved gambling, and ran up huge debts over the course of her life.

Her husband’s status meant that Georgiana could also be actively involved in political life. Although women could not vote, Georgiana became a central advocate for the Whig Party.

Georgiana and Chiswick House

Although the seat of the Dukes of Devonshire was Chatsworth in Derbyshire, Georgiana spent much time in London at Devonshire House and at Chiswick House, completed in 1729 and one of the greatest examples in England of neo-Palladian architecture.

Georgiana called Chiswick House her ‘earthly paradise’ and used it to entertain her close circle of friends, as well as to receive members of the Whig Party. She did much to the house and its gardens, planting lilacs, honeysuckle and climbing roses beneath the windows of her rooms. She also re-styled its interiors, mainly in the now lost wings that Georgiana and the duke added in 1788.

Visit Chiswick HouseRomantic Female Friendships

There has been much debate regarding the nature of Georgiana’s emotional and sexual life. Although she was married and took male lovers, it seems she also subscribed to the fashion for ‘romantic female friendships’.

Georgiana’s romantic infatuations could sometimes be disconcerting to their female recipients. They went beyond the conventional terms of endearment used between women of the period.

In 1776, having received a romantically emotional note from Gee, her friend the Countess of Jersey replied: ‘some part of your letter frightened me’. However, on two occasions the female subjects of Georgiana’s infatuation were more willing parties.

Gee’s first great crush was on the much admired Mary Graham, known as ‘The beautiful Mrs Graham’. They met towards the end of 1777 – Gee’s letters to Mary that year reveal her depth of feeling:

You must know how tenderly I love you … I am falling asleep and must leave you now, but I want to say to you above all that I love you, my dear friend, and kiss you tenderly.

Gee and Bess

Georgiana’s infatuation with Mary Graham ended in 1782 when, visiting Bath with her husband, she was introduced to Lady Elizabeth Foster (known as Bess). Bess was estranged from her husband and in financial difficulty. Gee and Bess struck up a very close friendship, and Gee invited Bess to live with her and her husband.

This developed into a type of relationship that approached what might be termed ‘polyamorous’. Bess became the duke’s mistress, an arrangement which lasted 25 years. During that time Bess and the duke had two illegitimate children.

Gee’s own feelings towards Bess are made clear in the fervent letters she wrote to her, despite the fact that she was very aware that Bess was her husband’s lover:

My dear Bess, Do you hear the voice of my heart crying to you? Do you feel what it is for me to be separated from you? … Oh Bess, every sensation I feel but heightens my adoration of you.

‘Passing The Love Of Woman’

Gee died in 1806, and Bess married William Cavendish to become Duchess of Devonshire herself. Following Gee’s death, Bess was moved to write that:

[Georgiana] was the constant charm of my life. She doubled every joy, lessened every grief. Her society had an attraction I never met with in any other being. Her love for me was really ‘passing the love of woman’.

Georgiana left her personal papers to Bess, who destroyed many of them. We can only guess as to the exact nature of Georgiana’s love ‘passing the love of woman’.

Find Out More

-

Listen to our Podcast

As part of this episode on Thomas, Earl of Lancaster and Dunstanburgh Castle, we delve into the relationship between King Edward II and Piers Gaveston and the Earl of Lancaster’s role in the latter’s downfall.

-

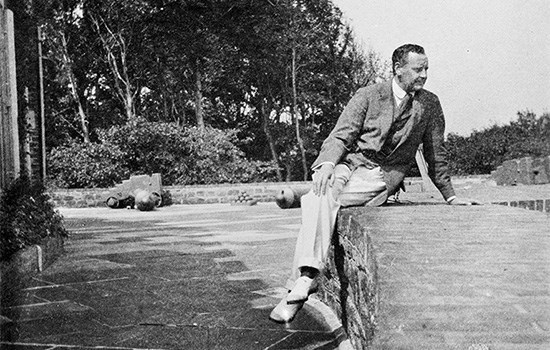

The Partners: Seely and Paget

Discover the story of John Seely and Paul Paget, who ran one of the most noteworthy architectural firms of the interwar period, and completed their masterpiece at Eltham Palace in 1936.

-

Sir Walter Hungerford and the 'Buggery Act'

Find out how Sir Walter Hungerford, owner of Farleigh Hungerford Castle, came to be the first man in England to be executed under the ‘Buggery Act’.

-

Lord Beauchamp, Walmer Castle and Homosexuality

William Lygon, Lord Beauchamp, was a known homosexual in the 1920s and 1930s, leading to a dramatic fall from grace. Read more about the man whose misfortunes inspired Evelyn Waugh’s ‘Brideshead Revisited’.

-

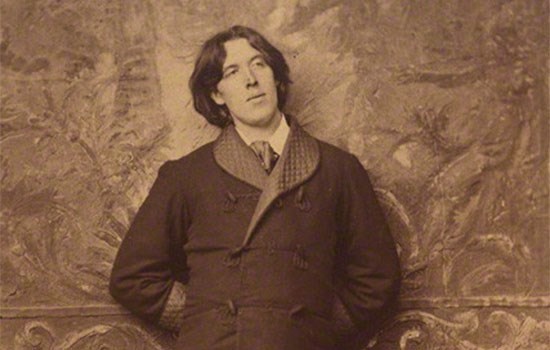

London Pride: LGBTQ Blue Plaques

Discover the stories behind some of London’s famous LGBTQ residents, honoured today with a Blue Plaque, and how many of them challenged public perceptions of gender and sexuality.

-

More LGBTQ+ History

LGBTQ+ history has often been hidden from view. Find out more about the lives of some LGBTQ+ individuals and their place in the stories of English Heritage sites.