A Moveable Feast

The Christian feast of Easter commemorates Christ’s suffering and death on the cross (Good Friday) and his resurrection three days later (Easter Sunday). The Gospels tell us this happened during the Jewish festival of the Passover, the date of which is determined by the lunar calendar, or the monthly cycle of the moon.

The early Christian Church adopted this lunar calculation for the date of Easter. In the early 4th century, it was agreed that Christ’s Resurrection on Easter Sunday must be celebrated on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the Spring Equinox.

This seems simple enough. However, there was disagreement about the date of the Spring Equinox, the days of the lunar month on which it was permissible for Easter Sunday to fall, and even the hour of the day when Easter Sunday began.

Different traditions, each capable of appealing to well-established precedent, had their own methods for calculating the date of Easter. In the middle of the 7th century, two such traditions came head-to-head in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria.

Conversion and Controversy

In the 5th century, Germanic peoples – the Anglo-Saxons – invaded and settled in what had been the Roman province of Britannia. These invaders did not share the Christian beliefs of many people in late Roman Britain, who were subsequently pushed to the western fringes of the British Isles.

Starting in the late 6th century, efforts were made to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. In 597, monks sent by Pope Gregory the Great in Rome arrived on the shores of Kent. Under the leadership of St Augustine, they established a base at Canterbury and gradually spread the Christian message across the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Irish monks, via their monastery at Iona off the western shores of Scotland, undertook a simultaneous and quite independent campaign of conversion.

Northumbria, then the dominant Anglo-Saxon kingdom, was Christianised from the 620s onwards by both Roman and Irish missionaries. But the Roman and Irish traditions had different practices, particularly in their ways of calculating the date of Easter. This inevitably led to disagreements about when Easter should be kept, which even extended to the royal household. Oswiu, King of Northumbria between 654 and 670, became a Christian under the influence of Irish monks. However, his wife, Queen Eanflaed, was from Kent and followed Roman practices. One year, the king was happily celebrating Easter Sunday while his wife was still keeping her austere Lenten fast and observing Palm Sunday.

The Synod of Whitby

Since Easter is the pivotal event in the Christian calendar, these issues were not just inconvenient. Some Northumbrian nobles began to wonder if they had made a mistake in adopting the Christian faith. As Bede, the great historian of the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons, put it:

This dispute rightly began to trouble the minds and consciences of many people, who feared that they might have received the name of Christian in vain.

In 664 Oswiu decided to settle the matter once and for all by calling a meeting of leading churchmen and nobles at the monastery he had founded at Whitby – or Streaneshalch as it was then known – which was then governed by his kinswoman, Abbess Hild – later St Hild. We know this meeting as the Synod of Whitby.

Colman, Bishop of Lindisfarne, presented the Irish case, with Wilfrid, a Northumbrian who had travelled to the Continent and was now abbot of Ripon, speaking for the Roman side. Each appealed to traditions established by Christ’s Apostles. Colman said he was following the practice of St John, maintained by the Irish missionary, St Columba of Iona (d. 597).

Wilfrid called upon the authority of St Peter. When Oswiu asked who was the gatekeeper of heaven', he quoted Christ’s own words in the Gospel of St Matthew:

You are Peter and upon this rock I shall build my church and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it and to you I give the keys to the kingdom of heaven.

As Colman could not cite similar authority for his position, Oswiu decided that Roman practices, including the method for calculating the date of Easter, should prevail. According to Bede, he pronounced:

Peter is guardian of the gates of heaven, and I shall obey his commands to the best of my knowledge and ability; otherwise, when I come to the gates of the kingdom, he who holds the keys may not be willing to open them.

Bede reported that all those present – high and low alike – agreed with the decision, though Colman and a few followers who refused to conform to Roman practices withdrew to Iona.

Clear-cut Divisions?

Some modern historians have interpreted the synod as early evidence of a clash between the centralising, authoritarian papacy in Rome and an independent native ‘Celtic’ or British Church. For these historians, events in 7th-century Northumbria foreshadowed the Reformation of the 16th century and the establishment of the Protestant Church of England, which rejected papal authority.

But in reality, this was far from being the case. The Irish and Roman missionaries shared the same fundamental beliefs – there was much more that united them than divided them. By the time of the synod, the southern Irish had already adopted the Roman calculation of Easter, which by the early 8th century was also being followed by monks at Iona.

Nevertheless, by standardising the practices of the Northumbrian Church according to the Roman tradition, the synod was a landmark in the history of the Church in England – one which brought together two Christian traditions already in the process of merging. From this point on, Anglo-Saxon Christians celebrated Easter, the holiest of all Christian festivals, on the same day as their co-religionists in mainland Europe. This unity of observance endures to this day.

Find out More

-

Plan your visit to Whitby Abbey

Follow in the footsteps of those like Bram Stoker who have been inspired by the abbey’s soaring Gothic ruins.

-

St Hild

As abbess of Whitby – a monastery for both men and women – Hild led one of the most important religious centres in the Anglo-Saxon world.

-

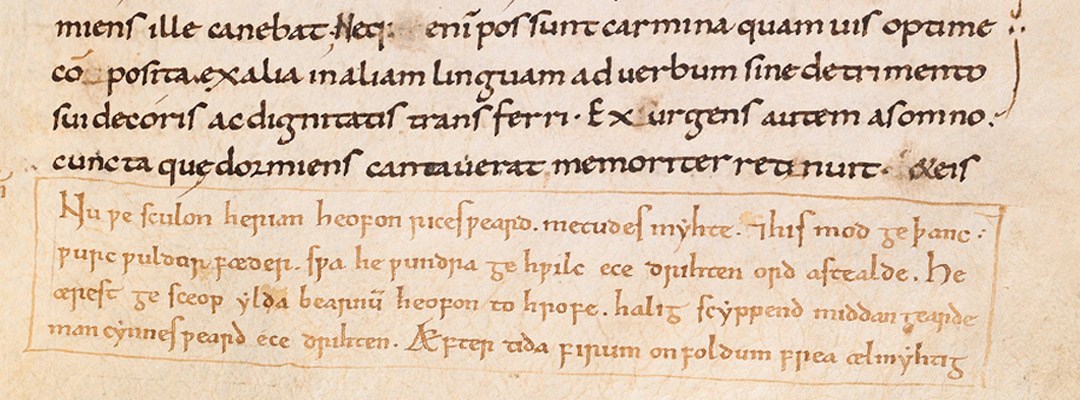

CÆdmon, Whitby and Early English Poetry

How Cædmon’s poetic awakening at Whitby produced one of the first fragments of English verse.

-

History of Whitby Abbey

Learn more about the history of Whitby Abbey, from its earliest Bronze Age origins to the present day.