The Early Middletons

The Middleton family has lived at Belsay almost continuously since the 13th century. They are first recorded there in 1270, when Sir Richard de Middleton, Lord Chancellor to King Henry III, owned the estate. He is the only member of the family in seven centuries to become prominent nationally.

In 1317 his grandson and heir, John, joined a local rebellion led by a cousin, Gilbert de Middleton. Both men were eventually captured and executed in London for treason. The Belsay estate was then forfeited and granted to a succession of owners, returning to the Middleton family by marriage in 1391. Since then it has remained in their possession, and the family still own the wider estate today.

There was already a high status house at Belsay by 1298 when Edward I visited while hunting in the area. The great fortified tower that still dominates the castle was, however, not built until the late 14th century, probably added to an existing manorial complex. The tower was both a statement of family pride and a response to the conflict and unrest in this border region between England and Scotland. It is one of the best-surviving examples of a pele tower – a regional type of fortification built by rich families in the late Middle Ages to defend themselves.

The Castle Wall Paintings

Fragments of wall plaster in the great chamber at Belsay Castle provide tantalising evidence of two superimposed schemes of domestic wall painting. The earlier scheme probably dates from the late 14th century, soon after the tower was built. It consists of thin, intertwining vine scrolls, supporting bunches of pale pink grapes and flowers. Now clear only around the windows, it once extended across the room.

Towards the end of the 15th century the great chamber was redecorated with a new three-tier scheme. The lower part of the wall is painted with a simple cube design in brown, grey and white. Above this is a line of heraldic shields, mostly hanging from lopped trees. On the east wall facing the entrance a hairy figure holds a larger shield. This is a ‘wild man’ – a medieval mythical figure and the heraldic supporter for the Middleton coat of arms. The trees and wild man are all set against the background of a green field decorated with clusters of red and white flowers.

The third tier, on the upper parts of the south wall, shows a naval scene, perhaps reflecting Sir John Middleton VII’s role as commander of two fleets against the French in the 1480s. The larger ships depicted are carracks, three-masted vessels used for both trade and warfare in the 15th century.

From Castle to Manor House

The union of the two kingdoms under King James I in 1603 brought relative peace to the border region. This encouraged local landowners like the Middletons to rebuild their houses with an emphasis on comfort rather than defence. At Belsay a mansion wing was added to the west side of the castle, converting it into a fashionable gentleman’s residence. A plaque over the entrance porch gives a construction date of 1614 and indicates that the builder was Thomas Middleton II, a staunch Presbyterian who supported Parliament during the Civil War.

Towards the end of his life Thomas moved to Dromonby, Yorkshire, leaving Belsay to his son, Charles. Belsay would not be the family’s main residence again until the 1670s, when Sir William Middleton, now a baronet, moved in with his second wife, Elizabeth. Finding the house in great disrepair he restored it, adding another wing to the west, visually counterbalancing the medieval tower.

An engraving of 1728 shows a formal walled garden in front of the castle, with rows of evergreen shrubs clipped into cones and balls, and statues of a wild man and wild woman, the heraldic emblem of the Middleton family.

Sir William Middleton II, the 3rd baronet, was a renowned breeder of racehorses, and adapted outbuildings in the castle yard as a stable block. He died in 1757 leaving large debts, so his stud horses and the content of the mansion had to be sold off. The fortunes of the family were restored, however, when his nephew William, the 5th baronet, married Jane Monck, the wealthy heiress of a London merchant.

Sir Charles Monck

The man who made the greatest impact on the Belsay estate was Charles, third son of Sir William Middleton, who became the 6th baronet in 1795 at the age of 16. The following year he changed his surname to Monck in order to inherit the Lincolnshire estates of his wealthy grandfather, Lawrence Monck. Sir Charles quickly established himself as a diligent manager of the estate, and was given control of his own affairs while still a minor.

Sir Charles had developed an abiding passion for the Classics, particularly Greek, while at Rugby School, so when he married his cousin Louisa Cooke of Doncaster in 1804, they chose Greece for their honeymoon. While in Athens during the summer of 1805 Lady Monck gave birth to a son, Charles Atticus, while her husband spent time visiting ancient sites, sketching what he saw and taking measurements. He also took a keen interest in the Greek landscape and native flora, taking notes in a detailed diary which he kept throughout the two-year trip.

Once back in England Sir Charles focused his attention on his estate and on county affairs. He was Whig MP for Northumberland between 1812 and 1820 and served for many years as a magistrate. Others saw him as bright if rather eccentric, with wide-ranging interests in gardening and botany, architecture, travel and horse racing. It is in the design of the hall and gardens at Belsay, however, that he most clearly left his mark.

The New Hall

Sir Charles’s new hall at Belsay is a masterpiece in the Greek Revival style, and one of the earliest examples of its use in domestic architecture in England. Its construction is remarkable as neither he nor his close acquaintances had any architectural training.

Work began in the summer of 1807, a year after Sir Charles and his wife returned from honeymoon. He drew inspiration from the ancient sites he had seen in Greece, and from books of Greek architecture in his library, producing a design of uncompromising austerity. The house, built of beautifully dressed sandstone blocks, is exactly 100 feet (30 metres) square and like a Greek temple sits on a crepidoma, or stepped plinth. The two massive Doric columns supporting the inset portico are copied from an ancient temple in Athens – the Theseion.

Despite its plain façade, the hall has a comfortable interior, arranged round the imposing central two-storey Pillar Hall, a layout inspired by the Roman villa as no suitable Greek precedent existed. The unplastered stone walls and coffered ceiling of the entrance hall create the impression of entering an ancient temple, and the decorative scheme in the main reception rooms is unashamedly Greek. The library boasts a Greek Revival frieze above bookcases, whose design was based on measurements Sir Charles had taken from the Erechttheion, a temple on the Acropolis in Athens.

Work was completed towards the end of 1817, and on Christmas day Sir Charles and his family moved the short distance from the castle into their newly finished hall.

Sir Charles Monck’s Travel Journals

Sir Charles travelled widely throughout his life, both in Britain and overseas, often recording what he saw in detailed diaries and notebooks. These provide revealing insights into his character and the interests that inspired the design of the house and gardens at Belsay. Throughout the journals he comments on architecture, but also on landscape and plants, and the scenes he has witnessed.

He first kept a journal during his honeymoon as he and his new wife passed through Germany, Austria and northern Italy on their way to Athens, where they arrived in May 1805. While in Greece he describes excursions to ancient sites, makes sketches and records measurements of buildings, but also talks at length about Greek landscape and flora, showing detailed knowledge of local plants.

Later travels around Europe in the 1830s were also vividly recorded, including a visit to the quarries at Syracuse in Sicily, which must have inspired the development and planting of the quarry garden at Belsay.

It wasn’t only Sir Charles’s travels abroad that informed his ideas for Belsay, however. His 1825–6 journal of an excursion to Yorkshire and Derbyshire includes visits to country seats such as Chatsworth and Wentworth Woodhouse, and to several nurseries reflecting his interest in plants. The journals reveal a particular interest in the gardens, and a keen eye for dramatic scenery, which may have influenced his own Picturesque designs.

The Picturesque Gardens

The vast gardens that provide the magnificent setting for the castle and hall are also largely Sir Charles’s work. The garden he inherited from his father in 1795 included informal planting, a serpentine drive and a lake. Sir Charles, however, was influenced by the emerging Picturesque movement, which favoured the shaping of landscapes less conventionally beautiful and more wildly naturalistic.

Creating a Picturesque landscape at Belsay was something of a challenge because of the gentle terrain. To the north and east of the hall Sir John had to be content with extending the 18th-century parkland, adding clumps of trees to break up the scene. To the south, however, the house overlooked a valley with a rocky hillside beyond. This he planted up with a mix of exotic conifers, Scots pine and native hardwoods to create the Crag Wood Walk. The valley below was dammed to form a new lake with a little cascade. The overall effect was a dramatic contrast to the adjoining parkland.

Immediately adjacent to the house Sir Charles varied the scene again, creating a broad terrace walk with parallel borders of brightly coloured annual plants.

To the west his romantic quarry garden, created where stone was cut for the hall, has ravines, pinnacles and sheer rock faces, inspired by Sicilian quarries. Contrasting with the strict geometry of the hall, and linking it with the castle, it is a remarkable example of the Picturesque style, with a microclimate that makes it possible to grow tender plants beyond their normal northern limit.

The layout of the Belsay gardens has remained largely unchanged since Sir Charles set them out in the early 19th century.

Sir Arthur Middleton

When Sir Charles died, aged 88, in 1867, he was succeeded by his grandson Arthur, who in 1876 changed his surname back from Monck to Middleton. Sir Arthur respected the spirit of the changes to Belsay made by his grandfather, but added embellishments of his own across the estate.

Sir Charles had demolished parts of the castle complex after moving his family into the new hall, creating a picturesque eyecatcher and smaller residence for the estate steward. Sir Arthur rebuilt the attached 1614 manor house to provide additional staff accommodation. He also employed the architect Charles Ferguson to reroof and restore the pele tower to its medieval form, reflecting his deep interest in the history of the Middleton family.

At the hall Sir Arthur made fewer changes. In the early 20th century he remodelled the reception rooms to either side of the library, created new kitchens in place of the housekeeper’s room and a suite of new servants’ rooms on the mezzanine floor above. Improvements were also made to the plumbing and drainage.

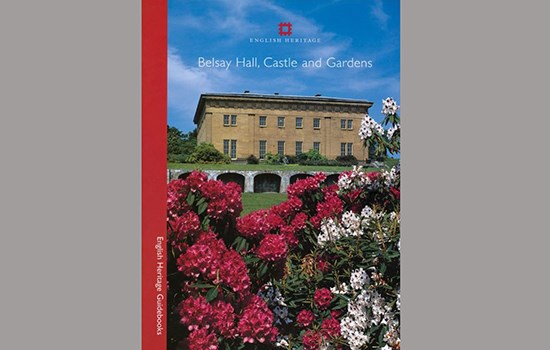

Sir Arthur’s interventions in the gardens were greater, though he respected his grandfather’s picturesque vision. As a true plantsman, he made full use of the many new species being introduced into England during the late 19th century. In the valley below the terraces he planted masses of red, purple and white rhododendrons to create the rhododendron garden. He also added the winter garden with lawns for croquet and tennis, and the yew garden and magnolia terrace to add greater colour and variety to the formal gardens by the house. The quarry garden was extended too and the planting diversified with more colourful and exotic species.

Belsay in the 20th century

In the early 20th century life at Belsay continued much as it had, with the Middletons entertaining regularly, supported by a substantial staff, though money was less plentiful than it once had been.

During the Second World War the hall was occupied by the Army and the gardens were not maintained, though the kitchen garden was used for provisions. Furniture was stored in the attic, and the bedrooms and servants’ quarters were occupied by soldiers. Later in the war, when Belsay became a divisional headquarters, Nissan huts were put up in the service yard and grounds to house additional troops.

The Middletons returned for a while after the war, opening up the castle and gardens to visitors to bring in some extra income. But in 1962 Sir Stephen Middleton, the 9th baronet, decided to move to Swanstead, a smaller, more manageable house on the estate. Many of the contents of the mansion were sold off at auction, and dry rot began to infest the empty rooms.

The hall, castle and gardens were taken into the guardianship of the state in 1980. There followed an extensive programme of repairs: wood and plasterwork was stripped out from many rooms in the hall and castle annexe to deal with the damp. The hall is now displayed without furnishings as an empty shell, in line with the guardianship agreement, revealing to visitors the fine craftsmanship that went into its construction.

The formal gardens have been restored to their appearance in the 1920s and 1930s, while in the quarry garden Sir Arthur’s exotic plantings have now reached their mature picturesque effect.

Visit Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens