Research on Rievaulx Abbey

Rievaulx Abbey has a long history of antiquarian and archaeological research because of the quality of its surviving remains.

Antiquarian Interest and Investigations

Dr John Burton included Rievaulx in his Monasticon Eboracense of 1758, recording not only its history but also telling of Thomas Duncombe’s new terrace and the views it provided.[1] TD Whitaker’s work on various abbeys and castles in Yorkshire included Rievaulx Abbey, the only work at the time to combine the Picturesque appeal of Rievaulx with serious scholarship.[2]

The high point in the recording of Rievaulx came with the publication of William Richardson’s Monastic Ruins of Yorkshire in 1844.[3]

Excavation

Rievaulx Abbey was exceptional in not being excavated by antiquaries in the second half of the 19th century. The Earls of Feversham refused to allow any excavation of the site, and were also reluctant to repair the rapidly failing ruins. This led to appeals to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in 1900 and the Office of Works (the predecessor of English Heritage) in 1911.

Sir William St John Hope, the leading monastic archaeologist of the period, was obliged to undertake his magisterial study of the ruins without recourse to excavation.[4]

Restoration

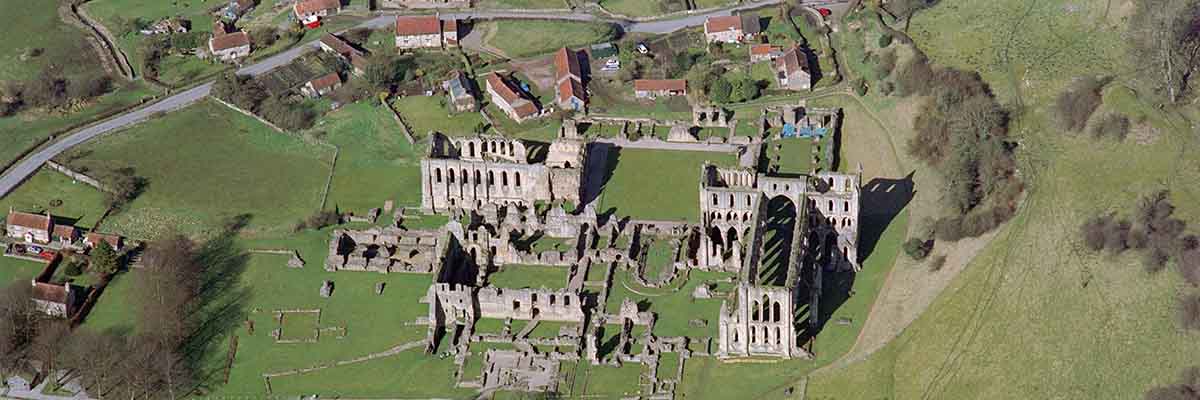

The site as it exists today is very much the creation of Sir Charles Peers, whose main concern was to remove all fallen material and conserve what remained in place, recovering a plan of the abbey’s central buildings while maintaining the surviving elevations.

His guide to the site is the only overview he published.[5] He did, however, publish two unusual aspects of the site, the incorporation of relics in altars,[6] and St William’s shrine in the chapter house.[7] William Harvey, an architectural assistant, recorded the excavation of the Romanesque nave, providing the evidence for its paper reconstruction.[8]

The clearance of the site produced thousands of objects, fallen stonework, window glass, pottery and metalwork that were carefully curated and slowly published.[9] The 1980s and 1990s saw the completion of the basic interpretation of the surviving ruins,[10] the analysis of charter evidence that provided the economic base for building,[11] and the understanding of the process of suppression and demolition.[12]

A major research programme begun in 1991 re-examined the work undertaken by Peers, the collection of architectural material recovered in clearing the site and the published and unpublished documentary evidence. This programme has established Rievaulx’s international significance as a major Cistercian monastery.[13]

Questions for Future Research

While the general development of Rievaulx Abbey is well understood, there are a number of areas in which further work is highly desirable.

English Heritage is currently working on the sites of the home grange of Griff, work which couples with surviving 16th-century documents; and work is being undertaken by the English Heritage Collections team to re-create a catalogue of the finds from the clearance of the site in the 1920s, to the extent that we can start the full study of those finds.

It is hoped that some of this work will help address the following questions:

- What form did Abbot William’s temporary monastery take? The potential church below the later cloister remains untested archaeologically, yet it is of critical importance to the understanding of the earliest Cistercian architecture, as no other buildings have been traced.

- How does the remodelling of the site in the 14th century reflect Cistercian life in the later Middle Ages? What were the buildings actually used for?

- A description exists of all the fittings of the church still in place early in 1539. To what extent does this show how the church was used in the late Middle Ages?

- The whole of the precinct at Rievaulx survives in meadowland and parts at least of the home granges of Griff and Newleys have been surveyed. What does this historic landscape, surviving principally as pasture, tell us about the economic development of the abbey?

- Does Rievaulx Abbey contain evidence for architectural ‘kit building’? Aelred’s great church at Rievaulx was constructed of rubble walling and ashlar dressings. The ashlar dressings are all marked on the exposed face with a Roman numeral, many of which can still be seen in situ, and many elements in store also have these numbers. Each number appears to relate to a particular template, but this has never been examined. This appears to be evidence for ‘kit building’, an explanation of the rapid construction of the 1150s and 1160s buildings, but further research is needed to determine this.

READ MORE ABOUT RIEVAULX ABBEY

Footnotes

1. J Burton, Monasticon Eboracense (York, 1758), 560.

2. TD Whitaker, A Series of Views of the Abbeys and Castles in Yorkshire, Drawn and Engraved by W Westall ARA and F Mackenzie with Historical and Descriptive Accounts by Thomas Dunham Whitaker, I (London, 1820).

3. W Richardson, The Monastic Ruins of Yorkshire from drawings by William Richardson, architect, with historical descriptions by Edward Churton, 2 vols (York, 1844).

4. W Page (ed), ‘Houses of Cistercian monks: Rievaulx Abbey’, in The Victoria History of the County of York, vol 3 (London, 1914) (accessed 10 September 2014).

5. CR Peers, Rievaulx Abbey, North Yorkshire (London, 1928).

6. CR Peers, ‘Two relic holders from altars in the nave of Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire’, Antiquaries Journal, I (1921), 271–82.

7. CR Peers, ‘Rievaulx Abbey: the shrine in the chapter house ’, Archaeological Journal, 86 (1929), 20–28.

8. W Harvey, ‘Nave excavations: Rievaulx Abbey’, The Builder (12 August 1921), 196–7.

9. For instance GC Dunning, ‘A lead ingot from Rievaulx Abbey’, Antiquaries Journal, 32 (1952), 53–63; GC Dunning, ‘Heraldic and decorated metalwork and other finds from Rievaulx Abbey ’, Antiquaries Journal, 45 (1965), 53–63.

10. P Fergusson and S Harrison, Rievaulx Abbey: Community, Architecture, Memory (New Haven and London, 1999); G Coppack, ‘Rievaulx Abbey’, in The Cistercian Abbeys of Britain: Far from the Concourse of Men, ed D Robinson (London, 1998), 160–64.

11. J Burton, ‘The estates and economy of Rievaulx abbey in Yorkshire’, Cȋteaux: commentarii cisterciences, 49 (1998), 29–94.

12. G Coppack, ‘Some descriptions of Rievaulx Abbey in 1538–9: the disposition of a major Cistercian precinct in the early sixteenth century’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 139 (1986), 46–87.

13. Fergusson and Harrison, op cit. The programme is directed by Peter Fergusson of Wellesley College, Massachusetts, and funded by the American National Endowment for the Humanities, Wellesley College, and English Heritage.