The Early Greys

For over 600 years the Wrest estate was home to one of the leading aristocratic families in the country, the de Greys. Each generation left its mark on the estate.

The family reached its greatest prominence when Edward IV made Edmund Grey his Lord Treasurer in 1463 and then Earl of Kent in 1465. More than 200 years later the formal gardens and the canal known as the Long Water were created by Amabel Benn, together with her son, Anthony, the 11th Earl, and his wife, Mary.

Wrest in the 18th Century

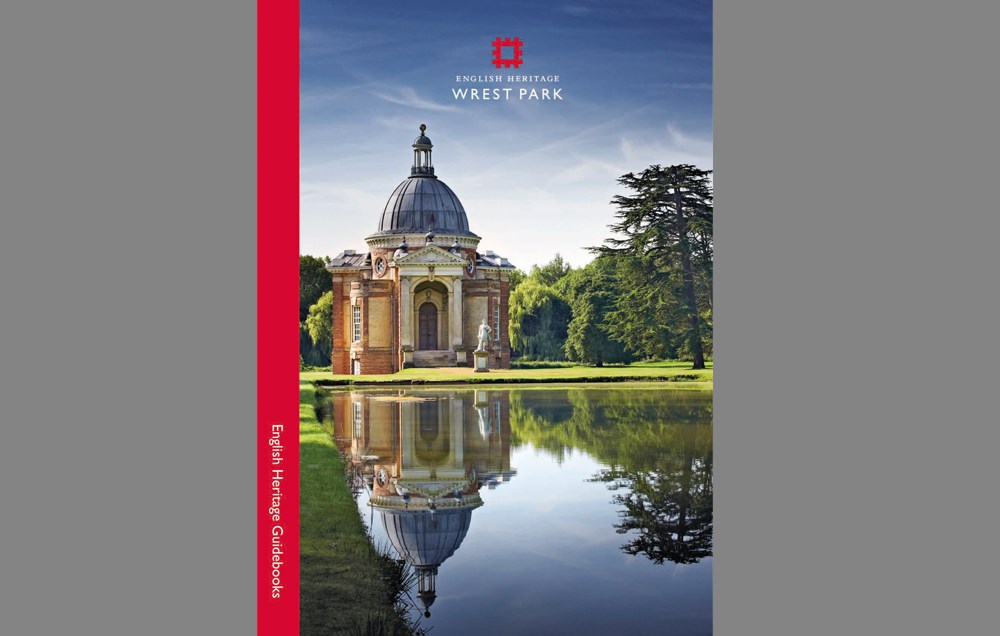

In the early 18th century Anthony’s son, Henry, Duke of Kent (1671–1740), laid out what is now Wrest’s most exceptional feature, its massive formal woodland garden, enclosed on three sides by canals. He employed leading architects and garden designers – including Nicholas Hawksmoor, Thomas Archer, Batty Langley and William Kent – to create an ordered landscape of woodland avenues ornamented with statuary and garden buildings. These included Thomas Archer’s baroque pavilion, with its trompe l’œil paintings by Mark Anthony Hauduroy.

On the duke’s death his granddaughter Jemima, Marchioness Grey (1723–97), inherited the estate. She showed a keen interest in the gardens. In 1758 she brought in ‘Capability’ Brown, a leader of the new English landscape style of the time, to soften the edges of the garden and remodel the park, while preserving the heart of the formal layout. Brown himself realised that to do more ‘might unravel the Mystery of the Gardens’.

Brown’s work is commemorated by the ‘Capability’ Brown column, built for Jemima by Edward Stevens. Jemima also added a Chinese temple and bridge, the Mithraic altar and a bath house.

The Pavilion Wall Paintings

Thomas Archer’s pavilion was designed and built between 1709 and 1711 and provided the duke with a pleasure house that was both a focus and a viewing point for the gardens.

One of the most stunning features of the pavilion’s Great Room – a large circular room with a domed ceiling – is its trompe l’œil wall-paintings by Mark Anthony Hauduroy. Trompe l’œil is a style of painting made popular in the 18th century which uses ‘tricks of the eye’ to make the painted objects appear three-dimensional. Using this effect Hauduroy mimics architectural features such as a coffered dome ceiling, fluted Corinthian columns, and niches which contain large urns and are flanked by classical statues. The paintings also include the de Grey coat of arms and family portraits, which are thought to celebrate the elevation of Henry Grey, then owner of Wrest Park, to the dukedom in 1710.

In 2019 our conservators visited sites with significant wall paintings such as those seen at Wrest Park, to assess and prioritise those most in need of conservation. The complex and delicate nature of wall paintings means many require specialist care to save them from serious deterioration or even permanent loss in the future.

English Heritage has now launched a campaign to raise the money required to bring specialist conservators on site and equip them with the latest technology for researching and restoring these precious wall paintings. Read more about the campaign via the link below.

Save our Wall PaintingsEarl de Grey’s New House

When his aunt Amabel (Jemima’s daughter) died in 1833, Thomas Robinson, 2nd Earl de Grey (1781–1859), inherited an outstanding garden with a large, crumbling house of medieval origins.

Rather than making improvements to the old house, de Grey, an accomplished amateur architect, demolished it and between 1834 and 1839 built a new house some 200 metres to the north. Unusually for the time, he chose to adopt an 18th-century French style of architecture both inside and outside the house, perhaps inspired by the estate’s formal gardens. Earlier he had a new gate and lodges built at the Silsoe entrance to the estate, also in the French style.

When it came to the gardens, Earl de Grey showed great respect for the legacy of his forebears. The upper gardens laid out in the 1830s between the new house and the earlier gardens were created in the French style, complementing both the architecture of the new house and the gardens of de Grey’s ancestors. A vast walled garden was created, replacing older kitchen gardens, and in 1857 the Evergreen Garden was laid out.

Wrest’s Recent History

Since 1900, Wrest has had a chequered history. It was rented to the American ambassador for a time, and was used as a convalescent home and later a military hospital during the First World War. In September 1916, however, a fire started and rapidly spread; the troops had to be evacuated, and the hospital never reopened.

Although it was repaired, Wrest was sold in 1917, after which it fell into decline. From 1948 it was home to the National Institute of Agricultural Engineering, later the Silsoe Research Institute. When the institute closed in 2006, English Heritage took over the house, and has begun an ambitious 20-year project to restore the gardens to their pre-1917 state. This project was funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund (now the Heritage Fund) and The Wolfson Foundation.

Find Out More

-

Collection Highlights

Explore highlights from the collection at Wrest Park including family portraits and 18th and 19th-century statues.

-

Wrest Park at War

Learn more about Wrest Park as a convalescent home and hospital during the First World War.

-

Visit Wrest Park

Explore the evolution of the English garden and take a stroll through three centuries of landscape design at Wrest Park.

-

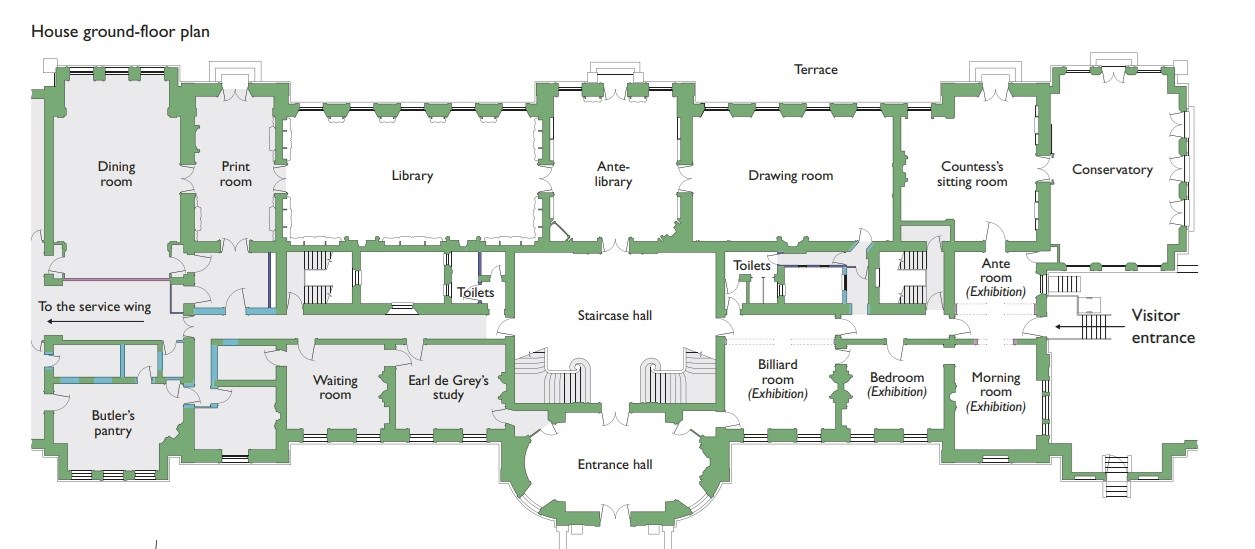

Download a Plan of Wrest Park

Download this PDF plan of Wrest Park House, Park and Gardens.

-

Buy the Guidebook

Buy the Wrest Park Guidebook to discover more about the house and its history.

-

More Histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.