Stuarts: Parks and Gardens

The influence of the great formal gardens of the Renaissance gradually gave way to the opulence of the Baroque during the Stuart period. Gardens increasingly displayed man’s dominance over nature and the fruits of scientific endeavour – both through their design and what was placed and grown in them.

RENAISSANCE GARDENS

Gardens reflected, to an extent, the political, religious and scientific turmoil of the first half of the 17th century, often displaying an intellectually complex iconography that was largely left to the viewer to interpret.

They were mostly geometric and rectangular in layout, and divided into squares or quarters called ‘compartments’ which were treated in various ways, as gardens or orchards for example. The patterns of interlacing knot gardens of the late Elizabethan era were gradually phased out in favour of geometric maze-like patterns or heraldic tracery, often inspired by Continental engravings.

Elaborate water features and grottoes in the Italian style with classical references appeared, as at Bolsover, Derbyshire, where the Venus fountain was added to the garden of the Little Castle between about 1628 and 1634.

Meanwhile, the compartment-style garden found favour with plant collectors and in smaller town gardeners. There was a fashion for topiary and for carefully planned ‘wildernesses’ – quarters planted with woody plants, intended to bewilder the visitor. One is recorded at Ashby de la Zouch Castle, Leicestershire, by 1615.

The English came up with a much simpler and cheaper variant of the Continental Renaissance garden: close mown turf divided into quarters by gravel walks, as seen in the Mount Garden at Audley End, Essex, where a wall enclosed a raised walk overlooking geometric paths between grass plats.

PARTERRES AND PROSPECTS

Such simplicity found little favour at the court of Charles I, whose wife, Henrietta Maria, employed the French designer André Mollet to inject flashes of French opulence into English gardens. Good examples include orangeries and elaborate parterres de broderie, as at Wimbledon Manor (c.1640).

In some gardens, prospect mounds crowned by an arbour or seat were built to afford views of the parterre beds and the surrounding countryside. In 1651, while in hiding at Boscobel House, Shropshire, the future King Charles II spent several hours reading in the arbour on the mount there.

THE CIVIL WARS

During the Civil Wars and Commonwealth period (1642–60) exiled Royalists struggled to maintain their estates, and their properties were often confiscated or split.

When the Royalist John Evelyn returned in 1652, however, he created a garden which became a horticultural testing ground, and after the restoration of Charles II in 1660 he became a founder member of the Royal Society. His book Sylva (1662) set out to promote not only tree planting in woods and avenues, but also different types of gardening: vegetables, exotics and fruit trees.

THE RISE OF HORTICULTURE

Charles II had avenues planted and canals dug at Hampton Court. Grand ornamental canals were also created at places such as Wrest Park, Bedfordshire, where the Long Water was dug in the early 1680s.

William and Mary made further improvements to the gardens at Hampton Court, adding the Fountain Garden, changing the Privy Garden and introducing florist, orangery and exotic plants. There was a craze for the latter, with the rapid development of stoves, hothouses and greenhouses to sustain them. Christopher Hatton, proudly designing ‘ye finest garden in England’ at Kirby Hall, Northamptonshire, in the 1690s, was keen to use rare imported plants such as ‘narcissus of Japan’, ‘seeds of ye soape tree from China’, and a ‘Hyacinth of Peru’.

The wave of new interest in planting and gardening was reflected in the creation in 1681 of the largest nursery to date, at Brompton, which provided ‘shaped’ trees (such as round-headed holly and pyramid yews), avenue trees, hedge plants, orangery and fruit trees. It also supplied trees and shrubs for the wildernesses and groves that were, by now, very fashionable.

PUBLIC GARDENS

After the Civil Wars, with normality returning, attention shifted to health and polluted air. This led to the creation of public gardens at the edge of a rapidly expanding London, such as New Spring Gardens (later Vauxhall). Public walks were also promoted near St James’s Park, with Pall Mall becoming a favourite destination.

PARKS AND COUNTRYSIDE

Parks continued to provide the country home not only with a supply of venison and sport, but also an appropriate setting for the house and garden. The most fashionable were embellished with avenues and small woodlands connected with the house. But if that was too expensive, or if the king had not licensed the owner to keep deer, the surrounding countryside could at least be ‘improved’ via enclosure, keeping commoners away from the house and its approach.

More about Stuart England

-

Stuarts: Architecture

From the grand country houses of the early Stuart period to Christopher Wren's new churches that rose from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

-

Stuarts: Commerce

The economy of much of Stuart England was largely based on traditional industries. London, however, was at the centre of a growing international network of trade.

-

Stuarts: Parks and Gardens

The influence of the great formal gardens of the Renaissance gradually gave way to the opulence of the Baroque during the Stuart period.

-

Stuarts: War

How the reorganisation of the Parliamentary army following the devastating Civil Wars of 1642–51 was the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.

Stuarts Stories

-

Charles I: a Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle

Learn about Charles I’s time as a prisoner of Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.

-

The Siege of Goodrich Castle

In June and July 1646, Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the Civil War.

-

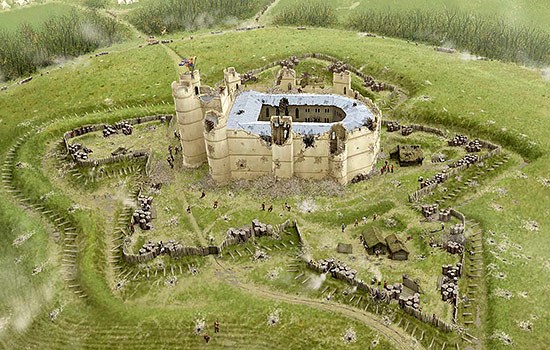

THE SIEGE OF DONNINGTON CASTLE

Discover how Donnington Castle in Berkshire held out for Charles I during a 20-month siege in 1644–6, and played a key role in the Second Battle of Newbury.

-

Charles II and the Royal Oak

How the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces during the Civil War in 1651, giving English history one of its greatest adventure stories.

-

Blanche Arundell, Defender of Wardour Castle

Read about how Lady Blanche Arundell heroically led a small band of men and women in defence of her home, Old Wardour Castle, when it came under siege during the Civil War.

-

Berry Pomeroy and the ‘Other’ Seymours

How an extravagant but unfinished castle tells a story of family rivalry and competitive housebuilding in 17th-century England.

-

Maritime Decline and the Battle of the Downs

How a major sea battle between the Dutch and the Spanish on the Kent coast, revealed as much about the English navy as it did about its participants.

-

The Countess of Kent and a Cookbook

One of the earliest celebrity cookbooks, includes cures for pox, plague and pestilence as well as recipes for culinary treats.

-

Border Reivers and Hadrian's Wall

How a fort, built for troops manning the frontier of Roman Britain, became a locus of crime and unrest in Stuart England.

-

Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, was one of the most prolific female authors and philosophers of the 17th century, writing at a time of immense political upheaval.