Significance of Audley End House and Gardens

Audley End demonstrates the origins and development of a great house and its landscape setting over five centuries, in response to changes in fashion and in the fortunes of its owners. Despite its major alteration and reduction, the house remains one of the most impressive examples of early 17th-century architecture in England. The 18th-century and 19th-century neoclassical and Jacobean Revival landscape, buildings and interior design are of equal importance.

The Jacobean House

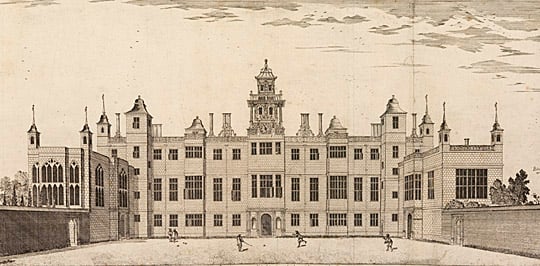

Audley End was the largest and most extravagant house built in early 17th-century England, adopting the plan and scale of the royal palace that it became, briefly, after the Restoration of 1660. While only elements of this building survive, their context is readily understood from, and illustrated by, the set of engravings made by Henry Winstanley in about 1676–88, themselves unique at the time in England.[1]

The house encapsulates the contemporary architectural tension between the restrained classicism of the main house and the florid Mannerism (now represented largely by its porches) that co-existed with it. The hall screen and plaster ceilings are among the best to survive from the period in England.

Continuity

The significance of Audley End is not confined its Jacobean apogee. That represents one stage in an exceptionally long period of evolution of the house and landscape, in which each successive stage was substantially shaped by, and retained elements of, its predecessors.

This great house was created not on a new site but by rebuilding on the footprint of the medieval Benedictine abbey. The abbey had been established in a long-used landscape in the Cam valley, alongside the London road, overlooked by an Iron Age hillfort, Ring Hill.

Elements from all these periods remain visible in the landscape, adapted and overlain by formal Jacobean landscaping, a late Georgian park and its ornamental buildings, and finally the mid-19th century partial return of formality.

Sir John Griffin Griffin and the 3rd Lord Braybrooke

The house is remarkable for the extent to which its owners from the mid-18th century onwards valued and so chose to retain much of its original 17th-century character and coherence, while leaving their own stamp with some of the highest-quality work of their time.

In the late 18th century Sir John Griffin Griffin kept external alterations ‘in keeping’ with the Jacobean house and restored the saloon as a picture gallery of his Howard ancestors. In rooms of no historic consequence, however, he employed Robert Adam to design some of the finest neoclassical interiors of their day, of which the Little Drawing Room stands out.

The 3rd Lord Braybrooke’s antiquarian, overtly Jacobean, interventions in the 1820s were more conservative. Despite initially intending to purge the house of Adam’s and Griffin Griffin’s work, ultimately he retained much of it and, in the decoration of the new reception rooms in the south wing, was evidently influenced by it. Audley End is an outstanding but idiosyncratic example of 19th-century Jacobean revivalism.

Collections

The rich architectural layering is reflected in the contents of the principal rooms which contribute much to the significance of Audley End as a whole. These contents, as they existed in the mid-19th century, remain substantially intact, and include work by the leading makers of the day. They are also exceptionally well documented by bills and inventories.

The collection of paintings is especially notable. Sir John Griffin Griffin acquired or commissioned a series of dynastic portraits to underline his noble lineage (his claim to the Barony of Howard de Walden was recognised in 1784). He also formed an impressive collection of Old Master paintings, including works by Hans Holbein, Hans Eworth, Pieter Claesz and Jan van Goyen, now displayed in the drawing room in their 19th-century arrangement.

The 3rd Lord Braybrooke’s marriage to Jane Cornwallis and his choice of Audley End as his principal residence brought both family collections to the house (displayed in the great hall and picture gallery). The late 17th-century portraiture is exceptional, including Peter Lely’s superlative self-portrait with the architect Hugh May (see Sources for Audley End House and Gardens).

The 4th Lord Braybrooke’s natural history collection constitutes one of the most important collections of its kind to survive in a country house.

Service Buildings and Gardens

The 18th- and 19th-century service range and yard to the north of the house are exceptional in the survival of the historic layout and fittings, particularly the kitchen, dairy and laundry. Only the interior of the brewhouse has been completely lost.

The kitchen gardens and stables also survive remarkably well (although the glass houses have been restored) and are particularly significant in illustrating aspects of the working of the house and estate in the 19th century.

Historical Associations

Audley End reflects and illustrates aspects of major events in English history. It was built by one of the leading courtiers of James I’s reign, became one of Charles II’s palaces, and has been shaped by architects and designers of the first rank.

During the Second World War, in 1942–4, Audley End was the headquarters of the Polish Section of the Special Operations Executive. Soldiers who volunteered to join the Polish underground movement were trained here before being dropped into their occupied home country.

Footnotes

1. Copies in several repositories and in the Audley End Scrapbook, c 1809.

Find out more about Audley End

-

HISTORY OF AUDLEY END

Read a full account of Audley End’s long and varied history, from the priory founded on the site in the 12th century to the present day.

-

Collection Highlights

View detailed images of some highlights from the diverse collection at Audley End – from paintings to natural history tableaux.

-

Description of Audley End

Read a description of this impressive house and its gardens, which have been shaped by various owners over the centuries.

-

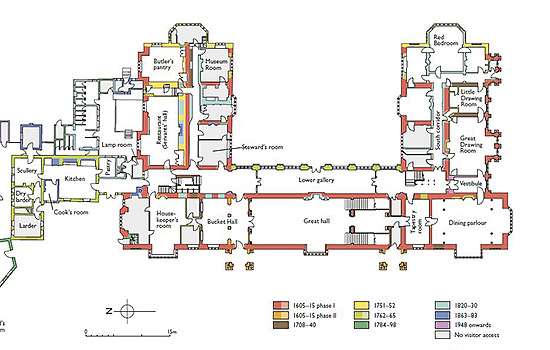

Download a plan

Download this PDF to explore detailed plans and elevation drawings of Audley End that reveal how the house has developed.

-

Research on Audley End

Read a summary of the current state of research on Audley End, with details of excavations, investigations and areas for future research.

-

Sources for Audley End

Use this list of written, visual and material sources for our knowledge and understanding of Audley End for further research into its history.

-

BUY THE GUIDEBOOK

The guidebook offers a complete tour and history of the house and gardens, and brings the house to life with stunning photos and historic images.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.