The first monument

The first monument at Stonehenge was a circular earthwork enclosure, built in about 3000 BC. A ditch was dug with simple antler tools, and the chalk piled up to make an inner and an outer bank. Within the ditch was a ring of 56 timber or stone posts. The monument was used as a cremation cemetery for several hundred years.

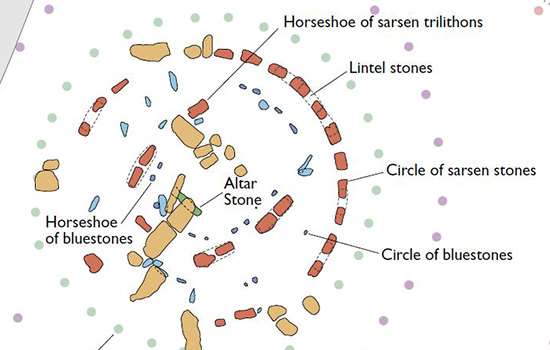

In about 2500 BC the site was transformed by the construction of the central stone settings. Enormous sarsen stones and smaller bluestones were raised to form a unique monument. Building Stonehenge took huge effort from hundreds of well-organised people.

Transporting the stones

There are two types of stone at Stonehenge – the larger sarsen stones and the smaller ‘bluestones’.

The sarsen stones are a type of silcrete rock, which is found scattered naturally across southern England. For many years most archaeologists believed that these stones were brought from the Marlborough Downs, 20 miles (32km) away, but their exact origin remained a mystery. However, recent research using a novel geochemical approach has not only confirmed that the Marlborough Downs were indeed the source, but has pinpointed the specific area that the sarsens most likely came from – the area known as West Woods, south-west of Marlborough.

On average the sarsens weigh 25 tons, with the largest stone, the Heel Stone, weighing about 30 tons.

Bluestone is the term used to refer to the smaller stones at Stonehenge. These are of varied geology but all came from the Preseli Hills in south-west Wales. Although they may not appear blue, they do have a bluish tinge when freshly broken or when wet. They weigh between 2 and 5 tons each.

The bluestones had a complex and varied history, with their current positions at Stonehenge only representing their final locations. Some of the bluestones are likely to have previously stood in a stone circle on the bank of the river Avon at West Amesbury henge, 1 mile (1.7km) to the south-east.

Some unspotted dolerite bluestones may originally have been part of a stone circle at Waun Mawn, in the Preseli Hills. Here, recent excavations have uncovered empty stoneholes, showing that at least six bluestone pillars were removed from this site in prehistory. When the bluestones were originally set up at Stonehenge they were erected in an arc of double stoneholes, known as the Q and R holes, before being later rearranged into their current arrangement of outer circle and inner horseshoe.

The Altar Stone is made of a type of sandstone found in south-east Wales, in the area of the Brecon Beacons or Black Mountains.

Download plans of StonehengeShaping the stones

Large quantities of sarsen and bluestone waste material, as well as broken hammerstones, have been found in the field to the north of Stonehenge, where the stones were worked into shape.

Sarsen and flint hammerstones in various sizes have been found at Stonehenge. The larger ones would have been used to roughly flake and chip the stone, and the smaller ones to finish and smooth the surfaces.

Analysis of a recent laser survey of the stones has revealed the different stoneworking methods used, and has shown that some parts of the monument were more carefully finished than others. In particular, the north-east side and the inner faces of the central trilithons were finely dressed.

To fit the upright stones with the horizontal lintels, mortice holes and protruding tenons were created. The lintels were slotted together using tongue and groove joints. These types of joint are usually found only in woodworking.

Raising the stones

To erect a stone, people dug a large hole with a sloping side. The back of the hole was lined with a row of wooden stakes. The stone was then moved into position and hauled upright using plant fibre ropes and probably a wooden A-frame. Weights may have been used to help tip the stone upright. The hole was then packed securely with rubble.

Timber platforms were probably used to raise the horizontal lintels into position. Then the final stage of shaping the tenons took place, to ensure a good fit into the mortice holes of the lintel.

Read more about Stonehenge

-

History of Stonehenge

Read a full history of one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments, from its origins about 5,000 years ago to the 21st century.

-

Plan of Stonehenge

Download this PDF plan to see the phases of the building of Stonehenge, from the first earthwork to the arrangement of the bluestones.

-

Research on Stonehenge

Our understanding of Stonehenge is constantly changing as excavations and modern scientific techniques yield more information. Read a summary of both past and recent research.

-

Why Does Stonehenge Matter?

Stonehenge is a unique prehistoric monument, lying at the centre of an outstandingly rich archaeological landscape. It is an extraordinary source for the study of prehistory.

-

Virtual Tour of Stonehenge

Take an interactive tour of Stonehenge with this 360 degree view from inside the stones, which explores the monument’s key features.

-

Stonehenge Reconstructed

Explore detailed reconstruction images depicting Stonehenge and nearby monuments from the early Neolithic period to the Bronze Age.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook includes a tour and history of the site and its remarkable landscape, with many reconstruction drawings, historic images, maps and plans.

-

England’s prehistoric monuments

England’s prehistoric monuments span almost four millennia. Discover what they were used for, how and when they were built, and where to find them.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.