Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.

GOVERNOR, COMMANDER AND JUDGE

The province of Britannia was governed for the emperor by a legate, an ex-consul of the highest, senatorial rank who also commanded the armed forces in the island. He was supreme judge, hearing disputes involving Roman citizens and individuals of high social status. Another official, the procurator, handled the provincial finances.

The legate and procurator had little administrative back-up, and the detailed work of government and justice was devolved to local government in the cities.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

These civic units, run by loyal local aristocracies, were the basic instrument of Roman rule throughout the empire. Each was governed by a town council ( curia), led by elected magistrates. They were responsible for settling local disputes and collecting taxes from the population in the extensive surrounding territory, and passing them on to the state.

As long as they were outwardly Roman in their values and met the tax demands of Roman officials, the local aristocracies were left to get on with it.

Unsurprisingly, this sometimes meant that they had to make up a shortfall in the anticipated level of tax from their territory. The system was notoriously prone to abuse: the greed and corruption of tax collectors was a factor in the Boudiccan revolt of AD 60.

TOWNS AND CITIZENS

There were 22 major towns in Britain. Seventeen of them were civitas capitals based on the tribal areas (civitates) into which the Britons had been organised in the course of the conquest. Wroxeter (in Shropshire), for example, was known as civitas Viroconium Cornoviorum, ‘Viroconium, the city of the Cornovii’.

Four were coloniae (Colchester, Gloucester, Lincoln and York), originally citizen settlements for legionary veterans. The status of London, largest city of the province and seat of the governor, is unknown.

In the early empire there was a gulf between those privileged to hold Roman citizenship and the non-citizen majority (peregrini). But citizenship gradually spread and in AD 212 it was granted to almost all free inhabitants of the empire – recognition that Rome was no longer a city but a world empire.

EMERGENCY MEASURES

In the late empire the system of government and taxation changed drastically to meet the emergencies of the times. After AD 300 imperial government was much more authoritarian, with a large bureaucracy of officials where previously there had been very few.

Britain, in common with other provinces, was subdivided – so that in the 4th century it was a diocese (governed by a vicarius) consisting of four provinces, each with its own governor. London was now rivalled by provincial capitals at Cirencester, Lincoln and York. Their growth reflected both their political importance as seats of governors with their attendant officials, and the development of a self-sufficient economy in the province.

DECLINE OF PUBLIC WORKS

Tax collection was still organised through the cities but was now largely in kind, to enable supplies to be sent directly to the frontier army.

Town councillors were no longer motivated to compete for status by erecting public buildings and serving their town – the route to status and privilege was increasingly through connections with the imperial bureaucracy. Officials therefore poured their wealth not into public buildings, but into private country estates and villas, like those at North Leigh in Oxfordshire and Lullingstone in Kent.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.

Roman Stories

-

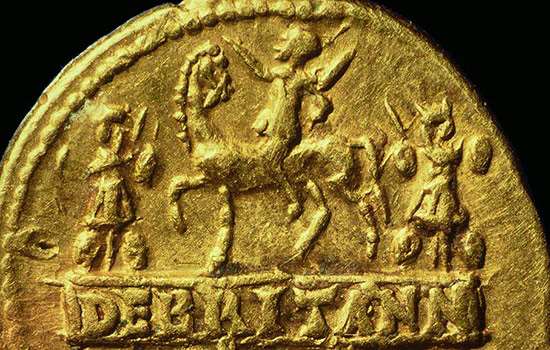

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

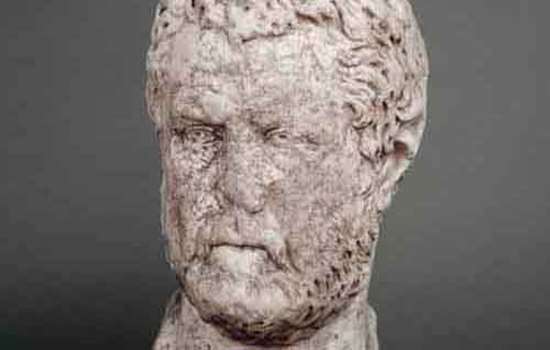

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.