Romans: Food and Health

The Romans introduced many new foods to Britain. Some people had access to professional medical care during the period, although most relied on herbal remedies.

New Plants

Before the Romans arrived the Britons cultivated cereals (mostly wheat and barley), and peas and beans, generally on a subsistence basis. The Romans introduced over 50 new kinds of food plants: fruits such as fig, grape, apple, pear, cherry, plum, damson, mulberry, date and olive; vegetables such as cucumber and celery; nuts, seeds and pulses such as lentil, pine nut, almond, walnut and sesame; and herbs and spices including coriander, dill and fennel. Many of these were then successfully grown in Britain.

Although recent excavations at Silchester in Hampshire have shown that many of these exotic foods were consumed there before the Roman conquest, this was exceptional: Silchester was the seat of a client-ruler with links to the Mediterranean world.

A CHANGING DIET

In the Roman period these new foods became much more widely available and revolutionised the diet of people in the growing cities and small towns, where market gardens and orchards growing cash crops must have become a common sight.

The new diet was adopted far more slowly among the rural poor, and hardly at all in the remote north-west parts of the province. Although even there, military communities were able to eat Roman-style foods.

Meat was more widely consumed under Roman rule. The average size of cattle increased, pigs were commonly kept, and some villas must have prospered from sheep farming. Beef was the favourite meat of the army of Hadrian’s Wall, and was supplied in large quantities to the Wall forts.

MEDICINES AND DOCTORS

Many of the new herbs were valued for more than just their nutritional qualities. Knowledge of their possible medicinal uses was widespread.

Anyone suffering from ill-health in Roman Britain might have had the option of turning to a professional doctor, if they had the money to pay – and then only if they had access to the kind of urban environment where doctors could be found.

Medical theories had come to the Roman world from Greece, and doctors were often of Greek or eastern origin. Prosperous town councillors and villa owners might have had their own private physicians, usually Greek slaves or freedmen.

The army had its own staff doctors. We know the name of some, like Anicius Ingenuus, a medical officer of the First Cohort of Tungrians who is commemorated on a tombstone at Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall. Some forts even had hospitals – remains of the one at Housesteads survive. Medical probes and surgical instruments are quite commonly found during excavations of both urban and military sites.

AMULETS AND EYE PROBLEMS

This kind of professional medical help would not have been available to the bulk of the population of Roman Britain, who relied on simple herbal remedies combined with the propitiation of deities, magic spells, and the wearing of amulets.

Those with access to baths would have kept cleaner – and smelled fresher – than the people of any other pre-modern period, but the waters of the baths may also have helped to spread the eye diseases that seem to have been prevalent in Roman times. Blocks of soluble eye ointment, stamped with a maker’s name, were popular in northern Gaul and Britain.

Roman Stories

-

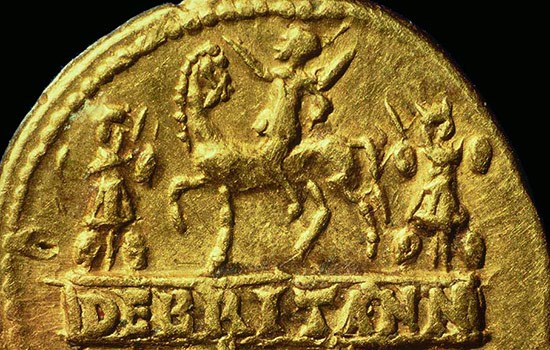

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

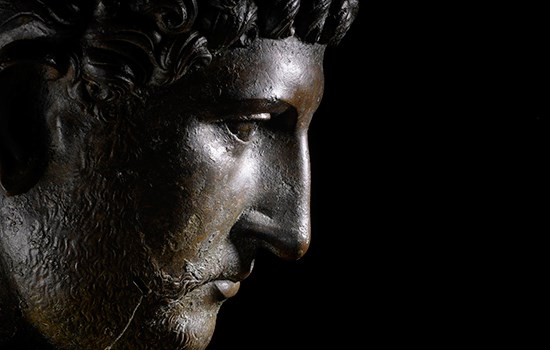

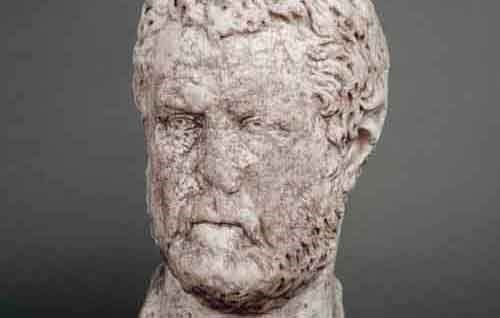

Emperor Hadrian

Discover the man behind the Wall. As emperor of the Roman Empire, Hadrian focused on securing the empire’s existing borders, and Hadrian’s Wall was the most impressive statement of this policy.

-

The Corbridge Lion and Changing Beliefs in Roman Britain

The exquisite sculpted lion discovered at Corbridge Roman Site offers a tantalising glimpse into the changing beliefs of Romans living in Britain.

-

Uncovering the Secrets of Hadrian's Wall

The remains of Birdoswald Roman Fort have revealed more about Hadrian’s Wall than any other site along the Wall.

-

Mithras and Eastern Religion on Hadrian’s Wall

A remarkable sculpture of Mithras found on Hadrian’s Wall reveals religious and military connections with distant parts of the Roman Empire.

-

The Mysterious Absence of Stables at Roman Cavalry Forts

How recent archaeological excavations on Hadrian’s Wall have revealed why it has always been so difficult to discover where Roman soldiers kept their horses.

-

The Mysteries of Corbridge

From strange heads on pots to missing temples, there are many things about Corbridge Roman Town that continue to puzzle us.

-

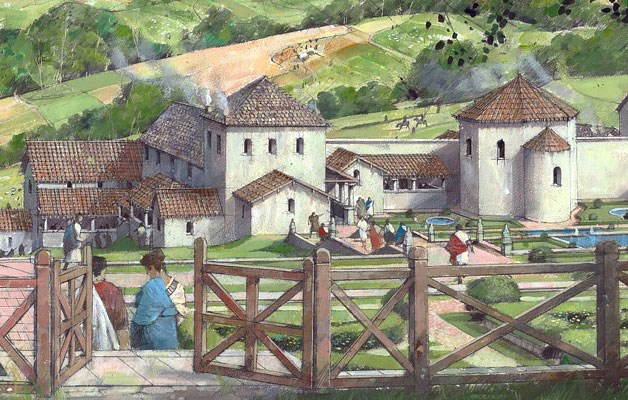

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

More about Roman Britain

-

Romans: Art

Rome’s success was built on the organised and practical application of ideas long known to the ancient world.

-

Daily Life in Roman Britain

The daily experiences of most people in Britain were inevitably touched by its incorporation into the Roman Empire.

-

Romans: Commerce

Most people in Roman Britain made their livings from a mixture of subsistence farming and exchange of specialist goods.

-

Roman Food and Health

Discover how the Roman conquest changed what people in Britain ate, and how they looked after their health.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

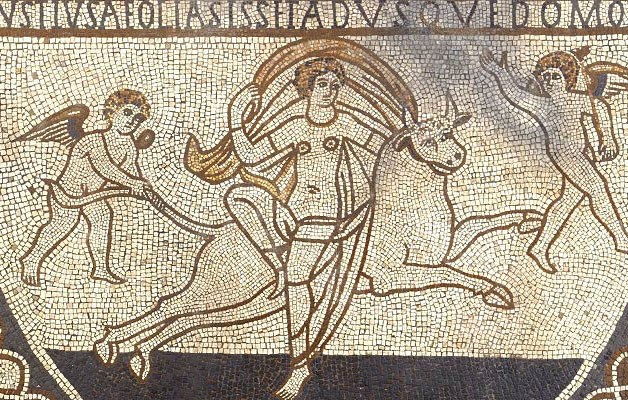

Roman Religion

The Romans were tolerant of other religions, and sought to equate their own gods with those of the local population.

-

Romans: Landscape

What kind of landscape did the Romans find when they conquered Britain, and what changes did they make?

-

Romans: Power and Politics

Britain was one of some 44 provinces which made up the Roman Empire at its height in the early 2nd century AD.