History of Chesters Bridge Abutment

The east abutment at Chesters was part of a large road bridge built in about AD 160 to carry the Military Way (the road accompanying Hadrian’s Wall) over the river North Tyne. The abutment, from which the easternmost arch sprang, incorporates the pier of an earlier and much smaller bridge which was part of the original construction of Hadrian’s Wall. The later bridge continued in use until the end of the Roman period and was demolished in the AD 670s to provide building materials for St Wilfrid’s church at Hexham.

The remains of the two successive Roman bridges at Chesters encapsulate some of the main developments in the history of Hadrian’s Wall.

The First Bridge

The original Roman route between Corbridge and Carlisle, now known as the Stanegate, crossed the River North Tyne by means of a ford, or more probably a timber bridge, situated half a mile or more downstream from Chesters.

When Hadrian’s Wall was built, the Stanegate continued in use. The purpose of the bridge at Chesters was to take the walkway along the top of the Wall across the river. Construction, or at least preparation of the site, began in the first or second season of Wall building (probably in AD 122 or 123).

The first bridge was built entirely of large stone blocks bound together with iron clamps set in lead, as is shown by the pier embedded in the east abutment of the later bridge. The easternmost of its arches was 4 metres wide; if this first bridge was the same length as its successor, it would have had nine arches. Such a large structure would have taken longer to complete than most of the other installations on the Wall.

The bridge was presumably left standing during the period from about AD 140 to 160 when the army on Hadrian’s Wall was sent north to hold the new defensive line on the Antonine Wall in Scotland.

The Road Bridge

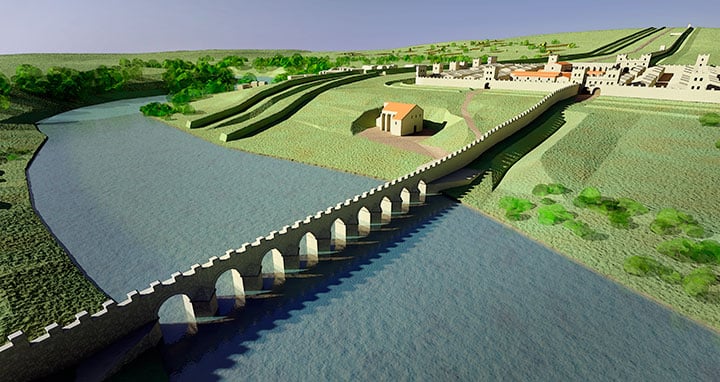

When Hadrian’s Wall was reoccupied after the Antonine Wall was abandoned, the first bridge was demolished and replaced by a road bridge. It had a carriageway 6 metres wide; on either side were stone parapets set in the tops of blocks which formed a moulded cornice above the faces of the arches. At intervals the parapets were interrupted by freestanding columns: as on other Roman bridges of a similar scale, these were probably crowned with statues.

The bridge was used to proclaim the power and prestige of the emperor and his empire. There is nothing in its architecture to distinguish it from bridges in the Mediterranean area of the empire, many of which are still in use. The only features which represented a concession to the military setting of the bridge at Chesters were towers placed behind its abutments, which effectively fortified it.

Little is known of the later history of the bridge during the Roman period. The only visible alterations are an extension of the south wing of the east abutment and the later insertion of a water channel. This passes through the base of the eastern tower and then under the adjacent road ramp to serve a water mill south of the visible remains.

Later 4th-century coins and pottery found in the area of the western approach ramp suggest that the bridge continued in use until the end of the Roman period in the early fifth century.

Demolition of the Bridge

The eventual demolition of the later bridge is a vivid illustration of how Anglo-Saxon society exploited its Roman material heritage.

The bridge was systematically dismantled in the AD 670s to supply building materials for St Wilfrid’s church at Hexham. It seems that all the stonework standing above ground in the east and west abutments was removed. Parts, at least, of the arches and piers were thrown into the river, perhaps mainly to salvage the several tonnes of lead bars which had been used to reinforce their fabric.

No further activity is known on the site of the bridge until excavations began in 1860.

READ MORE ABOUT CHESTERS BRIDGE ABUTMENT

About the Author

Paul Bidwell is an independent archaeology and heritage consultant. He has published extensively on Hadrian’s Wall, Roman south-west England, Roman architecture and Roman ceramics.