Gateways Club

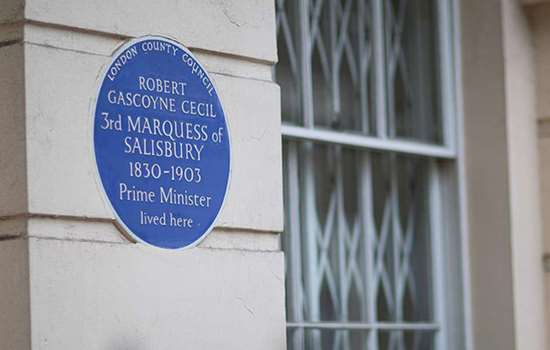

Plaque erected in 2025 by English Heritage at 239 King’s Road, Chelsea, SW3 5EJ, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

All images © English Heritage

Category

Food and Drink, Historical Sites, Music and Dance, Philanthropy and Reform

Inscription

Until 1985 this was the GATEWAYS CLUB a meeting place for lesbians

Material

Ceramic

The Gateways Club was the best-known and longest lived lesbian social venue in London. A blue plaque marks its location at 239 King’s Road, Chelsea.

The Gateways Club originally opened in about 1931. This part of Chelsea had a bohemian reputation, and musicians, writers and artists, including those from the Chelsea Arts Club around the corner, were among club regulars.

Gateways apparently acquired its name from the gates that originally stood at the entrance. The unremarkable green door in the side return to 239 King’s Road offered little clue as to the life below but became – and remains – a powerful landmark. Customers entered via a flight of steps and through a very narrow corridor, into the low-ceilinged room of the club. The walls were decorated, mostly by well-known artists who were members of the club

The club was not initially known as a lesbian venue, but lesbians were probably always part of its clientele. Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge are among the lesbian icons said to have drunk there in its early days. It was also a haven for non-celebrity lesbians, away from those who would have judged them, and from predatory men and the law, since women drinking in public houses were often assumed to be prostitutes.

Actively welcoming lesbians

During the Second World War, the club was taken over by a new proprietor who actively welcomed lesbian members. Ted Ware was a bookmaker who once ran the dog tracks at Stamford Bridge and Catford and claimed to have won the club in a poker game. In 1953, aged 56, Ware married 31-year-old Luigina (known as Gina) Harvey-Evans, who had been an actress but gave up this career to help Ted run the club. They had a daughter, Luigina, in 1955.

Gateways served a mainly straight clientele in the afternoons but became more lesbian in the evenings. There was no advertised suggestion that the club was a lesbian-friendly venue, but Ted made it clear that the women were welcome. He told one male customer, who complained that the couple he was attempting to harass were lesbians, ‘I’ll have a club full if I want. Now out!’

Black members and visitors, including artists and musicians, also found a welcome. Among them were club pianist Jack London, winner of a silver medal for sprinting in the 1928 Olympics, and Chester Harriott, the ‘Black Liberace’.

Gina, Smithy and the ‘Gateways Grind’

In the late 1950s, Gina took over management of the club. In 1959 she was joined by an American ex-air force woman known as Smithy, who came to live with the Wares. The nature of Gina and Smithy’s relationship was not openly discussed.

‘Behind a dull green door and down cellar steps … the girls are gathering to inaugurate the week-end. This is the famous Gateways Club’, wrote Maureen Duffy in her chapter on ‘Lesbian London’ in The New London Spy: A Discreet Guide to the City’s Pleasures (1966). Until then, knowledge of the club had been shared by word of mouth. Duffy also depicted the club, thinly disguised, in The Microcosm, which was described as the most significant novel about gay women since Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928).

Around this time, the social activities group of the lesbian magazine Arena Three, published by the Minorities Research Group, began to meet regularly at the club. At weekends, the dance floor would be packed as regulars danced the ‘Gateways grind’, which was, one of them remembered later, ‘very suggestive indeed’.

Women only

A women-only policy was introduced in 1967. Some regulars were annoyed by the change, including the artist Maggi Hambling, who had enjoyed it being ‘full of every kind of person’. Men were, however, permitted at Sunday lunchtimes, and exceptions were apparently made for family and friends.

In 1968, Gateways appeared in the International Guild Guide, which listed venues that welcomed (or at least were tolerant of) gay customers. The club only promoted itself as a lesbian venue in the gay press: a small ad in Sappho provided an introduction form for readers to give to Gina and Smithy.

Around this time, the club began to feature in mainstream media, including a BBC Man Alive documentary (1967) and The Killing of Sister George (1968), a film about the relationship between a butch aging actress and her passive, feminine young lover – a characterisation which reflected the club’s lesbian butch-femme scene. Surprisingly, though they risked exposure, 80 club members appeared as paid extras. Gina was Bea Ware, the receptionist-bouncer. She regretted the decision, as the film did not present a positive view of lesbianism or female sexuality. It was, nonetheless, the first Hollywood movie to focus exclusively on lesbian lead characters and offered many women their first glimpse of a lesbian lifestyle.

Challenges and close

In 1971 members of the Gay Liberation Front, who objected to what they saw as the Gateways’ non-politicised approach to gay life, protested outside the club, calling for those inside to ‘come out’. Gina, who had no time for political activism, called the police.

By 1980, the lesbian social club Kenric held its meetings at the Gateways, on Monday evenings when it was normally closed, and in 1982 Gay News wrote that even lesbians isolated in the Outer Hebrides were aware of the Gateways.

However, the club faced increasing competition from the opening of more same-sex bars nationally, a less gender-specific lesbian culture, and the rise of disco – which the Gateways attempted to accommodate on its tiny dancefloor.

Battling gentrification and threatened by the landlord with ending the lease for running a ‘lesbian club’, Gina fought back, arguing that Gateways was a women-only club, just as St James’s clubs were men-only.

Gateways received permission in 1983 to stay open until 1am, but neighbours complained and it lost its late-night liquor licence. The club finally closed its doors on 23 September 1985.

Further reading

-

Jill Gardiner, From the Closet to the Screen: Women at the Gateways Club 1945–85 (London, 2003)