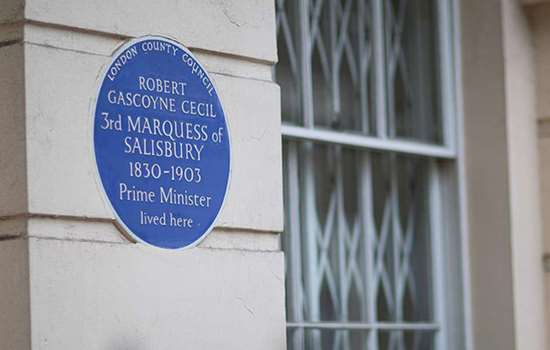

RIZAL, Dr José (1861–1896)

Plaque erected in 1983 by Greater London Council at 37 Chalcot Crescent, Primrose Hill, London, NW1 8YG, London Borough of Camden

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Writer, Political Activist

Category

Literature, Politics and Administration

Inscription

DR. JOSE RIZAL 1861–1896 Writer and National Hero of the Philippines lived here

Material

Ceramic

Notes

Replaces private plaque erected by the Philippine Society in 1955

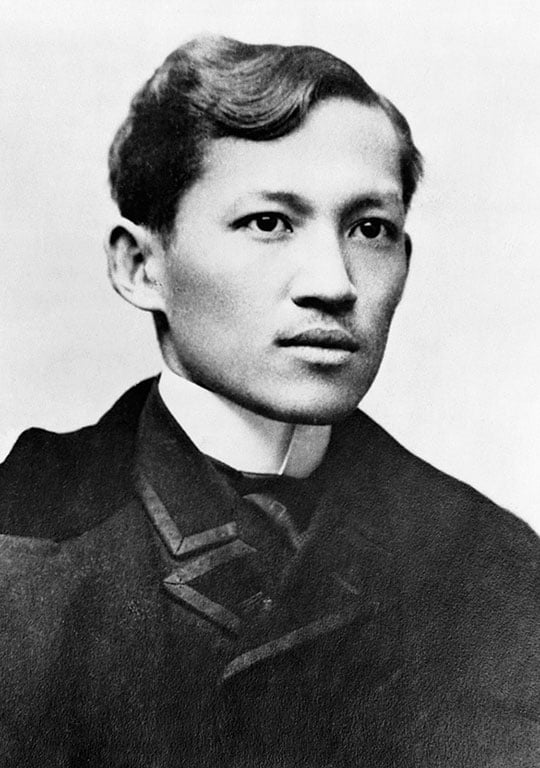

José Rizal is recognised as a national hero of the Philippines, celebrated for his writings advocating Filipino political, economic and social independence from Spain in the 19th century. He was commemorated with a blue plaque by the Philippine Society in 1955, which was replaced by the Greater London Council in 1983.

José Rizal was born in Laguna province. As a child, he demonstrated academic excellence, encouraged by his parents who invested in his education. His mother employed private tutors to supplement his formal schooling. Rizal completed his secondary studies at Ateneo Municipal de Manila at age 16, receiving awards in poetry, drawing, philosophy and languages.

In 1877, he enrolled simultaneously onto two programmes: Philosophy and Letters, and Medicine at the University of Santo Tomas. During the colonial period (1565–1898), the Spanish friars held significant power in religious, political and educational institutions. In some areas, friars had more influence than local governors. Facing racial discrimination from the Spanish friars who taught him, Rizal wrote: ‘The treatment the professors gave us was anything but paternal. It was instead harsh, full of prejudice, and at times humiliating. The Filipino students were often treated as inferior.’

Europe and the Philippine Propaganda Movement

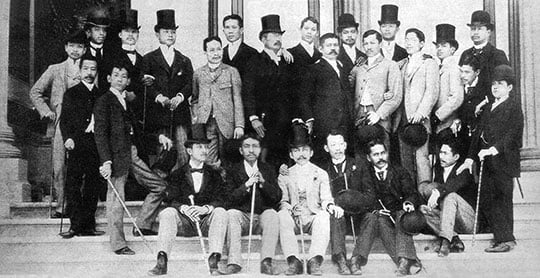

With support from his brother and without his parents’ knowledge, Rizal enrolled at the Universidad Central de Madrid, Spain, where he earned degrees in Philosophy and Letters, and Medicine. Throughout his studies, he took courses in sculpture, painting and drawing.

In Madrid, Rizal joined a group of Filipino intellectuals who formed the Philippine Propaganda Movement, which primarily used literature to advocate for political reform and promote equality between Filipinos and Spaniards. Key members included Marcelo H del Pilar and Graciano López Jaena, founder of the Filipino reformist newspaper La Solidaridad, to which Rizal frequently contributed. The newspaper became the main platform for the movement to send messages of nationalism.

While in Europe, Rizal wrote one of his most renowned pieces of writing, Noli Me Tangere, a novel exploring colonial oppression, church corruption, social injustice and the revival of Filipino identity under Spanish rule. Published in Berlin in 1887, the novel was smuggled into the Philippines and circulated among Filipinos, despite being banned by the Spanish authorities.

Rizal in London

Rizal’s time in London from 1888 to 1889 was pivotal in advancing his intellectual and nationalist work. While lodging with the Beckett family in Primrose Hill – in two rooms at 37 Chalcot Crescent, the 1860s terraced house that bears his blue plaque – he gained access to rare texts at the British Museum. There, he discovered Antonio de Morga’s Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, a first-hand account of pre-colonial life in the Philippines. Rizal saw this as a powerful tool to challenge colonial narratives and inspire Filipino pride.

In 1890, Rizal published a new edition of Morga’s Sucesos, complete with his own annotations. Dedicated to the Filipinos, the work highlighted pre-colonial customs, traditions and beliefs, countering the idea that Filipino culture began with Spanish influence. Rizal explained: ‘I have endeavoured to reproduce the sentiments of our ancestors … and correct the erroneous, often prejudiced accounts of the Spaniards.’

A year later, he published El Filibusterismo, the sequel to Noli Me Tangere, continuing his critique of Spanish colonial rule.

Return to the Philippines and execution

Rizal continued writing for La Solidaridad and networking with reformists. In Hong Kong and Macau, he drafted political proposals. In Manila, he founded La Liga Filipina, a political group that aimed to unite Filipinos into one society and promote self-reliance, political awareness and eventual self-governance. Just four days after its founding, Rizal was arrested by the Spanish authorities and sent to the then relatively remote area of Dapitan, Zamboanga.

When he was sent away, La Liga Filipina fractured. The moderate faction continued to pursue peaceful means of reform, whereas the more radical members, led by Andres Bonifacio, formed the Katipunan in 1892. This revolutionary group used Rizal’s name and writings to rally support for armed revolt, despite his opposition to violence.

On 23 August 1896, the Katipunan launched the ‘Cry of Pugad Lawin’, symbolically tearing their cedulas (residence certificates), marking the start of the Philippine Revolution. Rizal was rearrested in October of the same year and sent back to Manila, accused of having inspired the Katipunan revolt. He was tried for sedition, rebellion and conspiracy. Though no solid evidence linked him directly, forged documents and testimonies were used to convict him.

On 30 December 1896, Rizal was executed by a firing squad at Bagumbayan, Manila. The Spanish intended his trial to silence dissent, but it only intensified the revolution. Rizal became a martyr and a symbol of Filipino nationalism. Posthumously, Rizal was honoured as a national hero, celebrated for his intellect, moral courage and vision for a free and independent Filipino identity.

Further reading

-

Gregorio F Zaide and Sonia M Zaide, José Rizal: Life, Works and Writings (Quezon City, 1999)

-

León Ma Guerrero, The First Filipino (Manila, 1974)

-

Nick Joaquin, ‘Jose Rizal’, A Question of Heroes (Mandaluyong City, 2005)

-

Chris Antonette Piedad-Pugay & Peter Jaymul V Uckung, ‘Jose Rizal: Discover the human side of the national hero of the Philippines’ Tatler Asia