The medieval manor

Kirby Hall was built to the north of the medieval village of Kirby and probably incorporated elements of an earlier manor house. With easily worked soils suited to arable and pastoral farming, the area has a long history of occupation stretching back to the Romans. In 1086 there were six households recorded in the settlement, and this had grown little by the 16th century, with only ten able-bodied men recorded in 1539.

The manor passed through several hands before Humphrey Stafford of Blatherwycke (or Blatherwick), a nearby manor, bought it in 1542. Soon afterwards he styled himself as ‘of Kirby’, suggesting that Kirby had now become his principal residence.

After his death in 1548 his son, also Humphrey, inherited Kirby, and began building the house which remains today. By this time, little of the village remained, and the expansion of Kirby Hall’s gardens in the early 17th century probably swept away any surviving vestiges.

Creating Kirby: Humphrey Stafford

Humphrey began building Kirby Hall over 20 years after inheriting, perhaps initially spending more time at Blatherwycke. Although not a major player on the national stage, he was made Sheriff of Northamptonshire in 1566 – effectively the queen’s representative in the county – and was of some local importance.

If his house was anything to go by, Humphrey was also ambitious. Kirby Hall rivalled the houses of the great Elizabethan courtiers. Stafford’s Northamptonshire neighbours, such as Walter Mildmay at nearby Apethorpe, were also caught up in the desire to build ever more impressive houses to demonstrate their wealth and taste: in the second half of the 16th century there was a country house building boom in the area.

Stafford died in 1575, only five years after construction had begun, and when the house was still probably incomplete. Soon after, Kirby was sold to the courtier Sir Christopher Hatton (c.1540–1591).

Architectural innovation

Stafford employed the master mason Thomas Thorpe to build his home. Thorpe was a well-known local craftsman who worked elsewhere in the county, including Apethorpe. His son, John Thorpe, laid the first stone at Kirby when still a child, and went on to become a celebrated surveyor and architect himself, working at properties including Audley End in Essex.

Like many house designs of the time, Kirby’s was probably a collaboration between Stafford, Thomas Thorpe and the craftsmen on site. Historians have described what they created at Kirby as one of the most architecturally sophisticated houses of Elizabethan England, with one writing that Kirby ‘gathered together all the prevailing influences of the moment of its building’.

Kirby’s architecture combines familiar, traditional elements with new ideas arriving in England from the continent through travel and so-called ‘pattern books’ – in particular the influence of classical antiquity. The courtyard, for example, though decorated with traditional heraldic motifs, also includes classical ornament used in new and sophisticated ways. Although traditional in plan and layout, the facades of the courtyard show a newly fashionable concern with symmetry.

There are also native innovations, such as the pioneering use of huge windows on the northern facade. Such expansive use of glass would reach its peak at houses such as Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire.

The Hattons

From relatively humble beginnings, Christopher Hatton went on to hold important positions both at Court and in Parliament, and became a favourite of Elizabeth I. The height of his career came in 1587 when he was made lord chancellor – the most important statesman in the country.

After purchasing Kirby, Hatton set about completing Stafford’s work as well as enlarging and embellishing the Hall. Among his alterations was the addition of a new wing of state rooms – a lavishly decorated suite of rooms reserved for high-ranking visitors. Perhaps Hatton hoped his beloved queen, Elizabeth I, would be one such visitor, but she never came.

While he had amassed a fortune during his lifetime, Hatton died in debt in 1591. This was no doubt in part a result of his ambitious building endeavours both at Kirby and his nearby palatial ancestral home of Holdenby, which he rebuilt between 1578 and 1583.

Kirby eventually passed to Christopher Hatton’s cousin and godson, also Christopher Hatton (1581−1619), referred to here as Christopher Hatton (II). He developed the gardens, which were probably enclosed with high walls during this period. But according to his neighbour Sir Thomas Brudenell, he spent little time in Northamptonshire. Instead, he seems to have preferred London or Clayhall, his home in Essex.

Fit for royalty

Both Elizabeth I and James I took tours of their realm known as royal progresses, staying with their subjects en route. These were opportunities to demonstrate the monarch’s power and wealth. It was perhaps with a visit from the queen in mind that Humphrey Stafford and later Christopher Hatton (I) undertook their building projects at Kirby.

Elizabeth I never visited Kirby, but the house did become a favourite stop on James I’s annual royal progresses. He visited nine times between 1608 and 1624, and on one occasion stayed four nights. He was sometimes joined by Queen Anne, who had visited previously in 1605, and his sons. Located within Rockingham Forest, Kirby was a perfect base for a king (and queen) who loved to hunt. James visited during the stewardship of Christopher Hatton (II) and his wife, Alice Fanshawe, as well as that of their son, Christopher Hatton (III) (1605–70), who succeeded his father at the age of 14 in 1619.

The state rooms offered a fine and rich setting for entertaining. During a royal visit, the whole south-west wing of Kirby containing the state apartments would have been handed over to the royal party. The house and surrounds would have bustled with the king’s entourage and those eager to catch a glimpse of the monarch. Although hosting the king would have been a great honour, it was also an extraordinary expense, with the host expected to foot the bill not only for the monarch but the hundreds of people travelling with him.

Move the sliding bar to see the development of the north front of Kirby Hall, from the original house as built by Sir Humphrey Stafford (left) to the remodelling by Sir Christopher Hatton (III). © Historic England/English Heritage Trust (illustrations by Luís Taklim, Anyforms Design)

The Civil War years

A politician and scholar, Christopher Hatton (III) employed the mason-designer Nicholas Stone to modernise his home in the latest Court style in the 1630s. Hatton had amassed an important collection of historic manuscripts and music, and Stone’s work may have included the creation of a magnificent library. If so, it would have been one of the earliest purpose-built country house libraries in the country. During the 1630s and 1640s Kirby became an important centre for antiquarian and cultural research, and Hatton employed the antiquary Sir William Dugdale as his assistant.

For Hatton, though, this peaceful existence was soon interrupted by the English Civil Wars (1642–51).

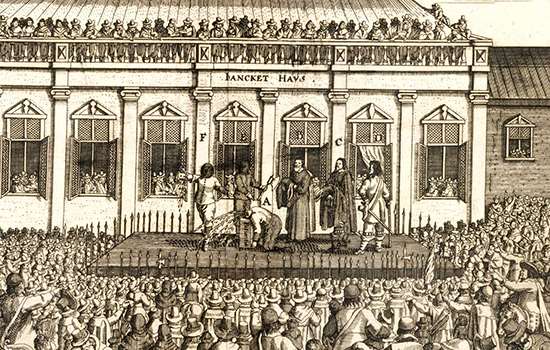

A supporter of the Royalist cause, he was rewarded for his loyalty by elevation to the peerage as Baron Hatton of Kirby in 1643. However, after Royalist-held Oxford fell to the Parliamentarians in 1646, he fled to France. He faced heavy fines and the threat that his property would be confiscated.

During Hatton’s absence Kirby was managed by his wife, Elizabeth, with the support of their estate steward, secretary and household musician, George Jeffreys. With limited access to family funds, life at Kirby was not easy. Elizabeth wrote in 1655 that at Kirby she found ‘all ye poor children well though stark naked Charles [her son] with only half a shirt … if I can get any body to lend me a little money I must be forced to quite clothe them all’.

After Hatton returned to England in 1656 he spent little time at Kirby, preferring to be London or in Guernsey, where he was governor in 1662–5. He died at Kirby on 4 July 1670 and was succeeded by his son, Christopher Hatton (IV) (1632–1706).

The ‘finest garden in England’

Sir Christopher Hatton (IV) also became governor of Guernsey and lived there during the 1670s. He and his family were at the governor’s castle one stormy night in 1672 when the gunpowder magazine there was struck by lightning: Hatton was blown from his bed onto the ramparts but was rescued by a black servant, James Chappell. Hatton’s three infant daughters also survived, but his mother, wife and the children’s nurse died.

Hatton was made Viscount Hatton in 1683 and after a successful political career retired to Kirby to focus on his passion: gardening. He remodelled the gardens extensively in 1685–6 and by 1700 little had been left untouched. In the remodelling Hatton took advice from the popular garden designer George London and his own brother, Charles, a plant collector, while both his second and third wives, Frances and Elizabeth, also played a role. Perhaps Hatton’s greatest pride and joy was his exotic and unusual collection of plants, some obtained from as far afield as the Pacific, East Asia and the Americas.

During Viscount Hatton’s time, the house was also updated. His second wife, Frances, oversaw extensive alterations in the 1670s as well as running the wider estate and managing accounts during her husband’s absences. Her correspondence describes rooms being plastered and panelled, new windows and chimneypieces being fitted, the creation of a chapel, and the addition of a new clock, the chime of which ‘you may hear … as far as Deene’ (1½ miles away).

Read more about James Chappell

Modernising Kirby

After the death of Christopher Hatton (IV), Kirby descended to his son, William (1690–1760), and later to the family of his daughter Anne, the Finches. They added the name Hatton to their own, becoming the Finch-Hattons.

Though the family’s main home was Eastwell Park in Kent, they did not abandon Kirby. George Finch-Hatton (1747–1823) modernised the interiors, and to fund the work held a large three-day sale in 1772, which cleared away unwanted fixtures and furnishings. Interiors were redecorated – for example, with fashionable wallpaper in some of the ground-floor rooms – and spaces put to new uses, such as a new library and billiards room.

Kirby passed to George Finch-Hatton’s son, George William Finch-Hatton, and his wife, Lady Georgiana Charlotte Graham, after their marriage in 1814. The newlyweds updated the furnishings, but when George came into his inheritance in 1823, they favoured Eastwell. The following year they put ‘Valuable and Elegant Household Furniture, Implements in Husbandry &C.’ up for sale, possibly to fund rebuilding at Eastwell Park, and a final sale took place in 1831.

By this time, however, the family’s land agent, Daniel Webster, was living in the house, since the Finch-Hattons no longer used it regularly.

Kirby in ruins

As the family withdrew from Kirby the house became home to farm servants, labourers and estate workers. The family rarely visited beyond charitable events in the grounds or as a stop on tours of their quarry in Weldon. The house fell into decay and soon became uninhabitable.

Kirby gained new admirers, however – both those interested in its fine architecture and those attracted by its romantic, semi-ruinous state. In 1899 one visitor likened Kirby to ‘a petrified poem – an epic in stone … it is impossible to look on this magnificent specimen … without feeling the keenest sorrow that it should be allowed to crumble’. Another, in 1913, imagined past lives: ‘where the courtiers trod a graceful measure grass grows … for days together no one goes to that great lonely house which once resounded with revelry and throbbed with life’.

Throughout Kirby’s decline there were glimmers of hope that the house would be preserved, and attempts were made to halt further ruination. Eventually, in 1930 the family transferred Kirby Hall to the Office of Works, making it one of the first country houses taken into state care. The estate’s former shepherd, Mr Hawkes, and his wife lived there as custodians, with their Alsatian puppies and cat.

The science of garden archaeology was pioneered at Kirby in the 1930s and the house underwent several campaigns of research, repair and conservation. Today, the house – stripped to its bare bones and ruinous in some places, in others decorated to give a sense of the house in the 19th century – allows visitors to imagine the vibrant life of its past occupants, as well as to appreciate its beauty as a romantic ruin. The gardens have been recreated to reflect their late 17th-century form.

Further reading

Cady, M, ‘The conservation of country house ruins’, PhD thesis, University of Leicester, 2014 (accessed 16 Sept 2025)

Cole, E, ‘The state apartment in the Jacobean country house, 1603–1625’, PhD thesis, University of Sussex, 2011 (accessed 16 Sept 2025)

Girouard, M, Elizabethan Architecture (London, 2009)

MacArthur, R and Stobart, J, ‘Going for a song? Country house sales in Georgian England’, in Modernity and the Second-Hand Trade: European Consumption Cultures and Practices, 1700–1900, ed J Stobart and I Van Damme (Basingstoke, 2010)

Thurley, S, Kirby Hall (English Heritage guidebook, Swindon, 2020)

Worsley, L, Kirby Hall (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2000)

Find out more

-

Visit Kirby Hall

Explore the beautiful Elizabethan and 17th-century ruins, discover the recreated gardens and trace the story of Kirby Hall’s rise and fall.

-

Buy the guidebook

This lavishly illustrated guidebook includes a tour of the spectacular remains and a vivid account of Kirby Hall’s history.

-

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan of Kirby Hall to see how its buildings developed over time.

-

Speaking with Shadows Podcast: The Heroic Servant of Kirby Hall

In this episode of our Speaking with Shadows podcast, Josie Long heads to Kirby Hall on the trail of James Chappell.

-

English Heritage Podcast: England's lost composer: George Jeffreys at Kirby Hall

Find out more in this podcast about George Jeffreys, the estate steward and secretary at Kirby who was also an accomplished musician.

-

THE ENGLISH CIVIL WARS

Discover how the Civil Wars unfolded at English Heritage’s properties – from ferocious sieges to a castle where Charles I was held prisoner.