George Villiers

George Villiers, born in 1592, was the son of Sir George Villiers, squire of Brooksby in Leicestershire, who had died in 1606. His mother, Mary Beaumont (d.1632), was ambitious for her son, and had George educated for success as a courtier, more than as a country gentleman. He learnt to dance, fence and speak French. Bishop Goodman of Gloucester wrote that he was:

the handsomest man in all of England, his limbs so well compacted, and his conversation so pleasing, and of so sweet a disposition …

Others thought so too. A number of courtiers, led by Sir John Graham, a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber, had been grooming George for success. They were inspired by their hatred of King James’s current favourite, Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset. They bought Villiers a fashionable wardrobe, and arranged for him to be present at Apethorpe.

James I and Robert Carr

King James had had a troubled and lonely early life. His mother, Mary Queen of Scots, disappeared from his life when he was in infancy.

In 1589 James, aged 23, married Anne, daughter of the King of Denmark, then aged 15. For some years the marriage was a close and affectionate one. They had seven children, of whom only three survived infancy, as well as at least three miscarriages. After the death in infancy of their last child, Princess Sophia, in 1606, Anne declared that she wanted no more pregnancies. The couple began to live apart and the following year James formed a passionate attachment to Robert Carr, then 17 years old, the son of a Scottish gentleman.

Having risen by royal favour, in 1615 Carr became embroiled in a scandal with his wife, Frances Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk. They were both accused of plotting the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury, a one-time friend of Carr who had opposed the couple’s marriage. Frances and Robert were found guilty and imprisoned in the Tower. But James would not countenance their being executed and in 1622 the couple were released and exiled to their country estate. By this time, there was a new favourite in the king’s life.

‘Sweet Steenie’ and ‘Dear Dad’

George Villiers came to James I’s attention shortly before the Carr scandal exploded. His advancement was spectacular. He became Cup-bearer in 1614; Gentleman of the Bedchamber in 1615; Master of the Horse, Baron Whaddon and Knight of the Garter in 1616; Earl of Buckingham in 1617; Marquess of Buckingham in 1618; and Duke of Buckingham in 1623.

The king christened his new favourite ‘Steenie’ after a passage in the Acts of the Apostles where the first martyr, St Stephen, is said to have the ‘face of an angel’.

Several letters from James to ‘Steenie’ survive, variously addressing him as ‘only sweet and dear child’, ‘sweet Steenie gossip’, ‘sweet heart’, ‘sweet child and wife’, and signing himself ‘thy dear dad’, ‘dear dad and steward’, and ‘dear dad and husband’. In one letter James wrote:

I desire only to live in the world for your sake, and I had rather live banished in any part of the world with you, than live a sorrowful widow-life without you. And so God bless you, my sweet child and wife, and grant that ye may ever be a comfort to your dear dad and husband …

It seems clear that this goes well beyond conventional early-modern expressions of friendship, and could be described as a love letter. Not that there was anything covert about the relationship. In 1617 the king justified his favour for George to the Privy Council:

I, James, am neither a god nor an angel, but a man like any other. Therefore I act like a man and confess to loving those dear to me more than other men. You may be sure that I love the Earl of Buckingham more than anyone else, and more than you who are here assembled. I wish to speak in my own behalf, and not to have it thought to be a defect, for Jesus Christ did the same, and therefore I cannot be blamed. Christ had his John, and I have my George.

The affection appears to have run in both directions and George’s letters to the king were equally affectionate. At the time monarchs were regarded with such a degree of reverence that for a young man of no particular fortune to be regarded with such devotion by the king himself would have been an overwhelming experience.

James and George at Apethorpe

The Mildmays’ house, Apethorpe, where James and George had first met, was a favoured hunting retreat for the king. In 1622 Sir Francis Fane, husband to Mary Mildmay who inherited the house on her father’s death in 1617, enlarged the house ‘for the more commodious entertainment of his Majesty’, creating the magnificent state apartments for which Apethorpe is justly famous.

During the conservation of the house in 2004–6, a blocked doorway was discovered between the king’s bedchamber and the second chamber in the suite, known as the Duke’s Chamber. James and George probably occupied these rooms during the king’s last visit to the house in 1624. So James and George on occasion shared a bed, and at Apethorpe, had connecting bedchambers. This has been taken to mean that they had a sexual relationship, though we cannot know this for certain.

At the time, any overt homosexual activity would have been labelled sodomy, which was banned both by canon law and the law of the land. James I, writing to his Lord Chancellor, Francis Bacon, referred to sodomy as one of ‘those horrible crimes which ye are bound in conscience not to forgive’. Yet George wrote to James that on a journey he had:

… entertained myself, your unworthy servant, with this dispute, whether you loved me now. … Better than at the time which I shall never forget at Farnham, where the bed’s head could not be found between the master and his dog …

Power, Influence and Assassination

George Villiers rose so high in favour that his influence would begin to change the course of history. He had not only won the love and respect of the king, but also that of the royal family. James’s queen, Anne, had detested Robert Carr, but seems to have been genuinely fond of George. He also developed a close friendship with their son, Prince Charles (later Charles I).

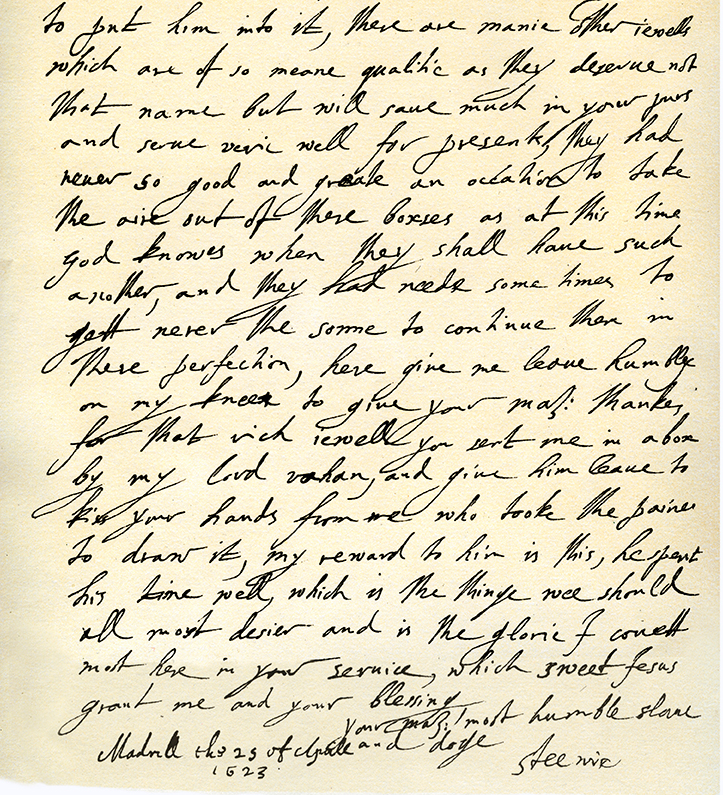

So close was their friendship that in 1623 George, now the Duke of Buckingham, accompanied Prince Charles on a long and hazardous journey across France to Spain, to try to conclude the negotiations to marry Charles to the Infanta Maria Anna, sister of Philip IV of Spain. Buckingham had rows with Philip IV’s favourite, the Count of Olivares, offended the Spanish with his arrogant behaviour, and destroyed any possibility of a Spanish marriage.

He took the failure of the Spanish match as a personal slight, and on their return to England he lobbied for a reversal in policy, leading to a war between England and Spain in 1624.

Buckingham’s grip on royal favour, and the levers of power and patronage, survived the death of James I in 1625: he wept on hearing the news. With Charles on the throne, Buckingham then presided over a war with France in 1627–9 in support of the French Protestants. Buckingham may have been the Lord Admiral of England, but he was no great military leader, and his expedition to the port of La Rochelle was an expensive fiasco.

Buckingham led England into two unwinnable wars with the greatest powers of the age. His erratic management of England’s foreign policy was ended with dramatic suddenness, not by any withdrawal of royal favour, but by his own assassination at an inn in Portsmouth by a disgruntled army captain, John Felton: he was 36 years old. Charles I was distraught at his death.

Buckingham’s Legacy

Little of Buckingham’s world remains today. Nothing survives from his time at either of his country houses, New Hall in Essex or Burley-on-the-Hill in Rutland, nor does anything remain of the grandiose renovation he carried out at Dover Castle in 1625–6.

Two architectural fragments bear witness to his career: the York Water Gate, the ornate river-entrance to his London residence, York House, which still stands in Embankment Gardens; and that enigmatic doorway that links the King’s Chamber and the Duke’s Chamber at Apethorpe Palace.

Buckingham survives most vividly in the extraordinary correspondence between him and his king, and in the portraits which convey so much about him and his world – the extravagance and pride, the air of courtly fantasy, the arrogance of power, and the remarkable personal beauty which entranced King James and made his fortune.

Further Reading

Lockyer, R, Buckingham: The Life and Political Career of George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham (New York, 1981)

Lockyer, R, King James VI and I (London, 1998)

Morrison, K (ed), Apethorpe: The Story of an English House (New Haven and London, 2016)

Explore More

-

England’s Rulers and their ‘Favourites’

We explore LGBTQ+ history and the private lives of four rulers who had same-sex relationships with their ‘favourites’.

-

Visit Apethorpe

A stately palace with one of the country's most complete Jacobean interiors.

-

LGBTQ+ History

LGBTQ+ history has often been hidden from view. Find out more about the lives of some LGBTQ+ individuals and their place in the stories of English Heritage sites.