Iron Age and Roman Leicester

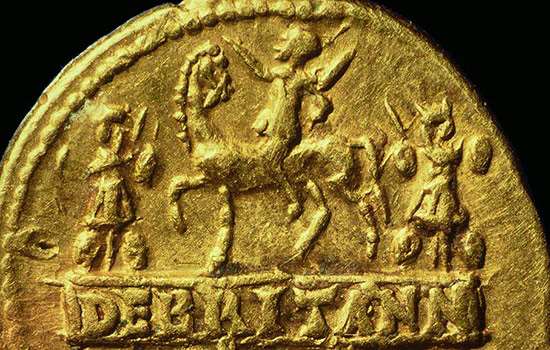

Two thousand years ago, Leicester was an important settlement for the Corieltauvi people, who occupied the area known today as the East Midlands during the late Iron Age (from around 100 BC).

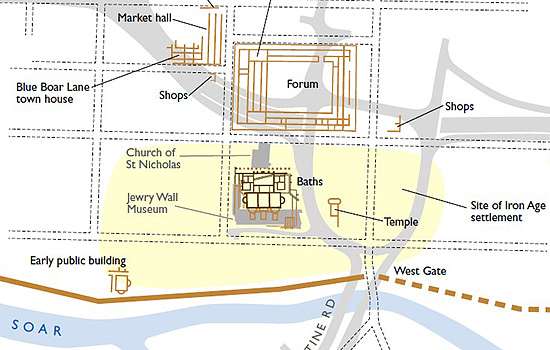

The Romans appear to have occupied Ratae Corieltauvorum (the Roman name for Leicester) soon after their conquest of Britain, which began in AD 43. The early development of the Roman settlement is unclear, but by the 2nd century a new rectangular street grid had been laid out. This coincided with the town being established as the capital of a civitas (territory). Civitates were established to secure Roman rule over the province of Britannia. The Roman road network connected Ratae to other Roman towns including Lincoln (Lindum Colonia), Wroxeter (Viroconium Cornoviorum) in modern-day Shropshire and Aldborough (Isurium Brigantum) in Yorkshire.

From this time on, Ratae expanded rapidly, reaching its peak in the late 3rd century. As well as many public buildings (see below), within the town there were shops and a wide variety of houses, from simple rectangular structures built along street fronts to the more lavish dwellings belonging to richer citizens. These were often modelled on Mediterranean designs, and included a large central courtyard.

Public buildings

At the town’s heart were its public buildings, chiefly the forum-basilica complex, which was the centre of local government and trade, and the public baths, completed in AD 160. There were also temples to Roman gods. The building of a forum and a public bath symbolised the coming of Roman power, law and culture to towns like Ratae. Their importance was reflected in their elegant designs and intricate mosaics.

The forum and baths were also integral to a Roman lifestyle. At the forum-basilica there would have been administrative offices, a shrine, and the offices used by the magistrates and council to provide justice and administration for the tribal area. Markets were regularly held in the open square of the forum.

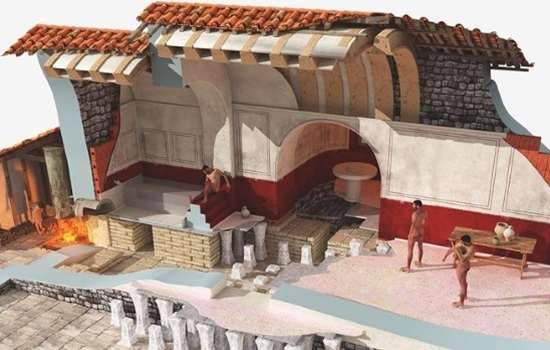

The Romans considered a trip to the public baths an everyday necessity. Bathing communally was a distinctively Roman activity and widely practised by men and women, free and enslaved. At the baths people could meet friends, exercise, socialise, eat and unwind.

The baths at Leicester seem to have stayed active until their eventual abandonment around the early 5th century.

The baths

People entered the baths via a long rectangular building (50 x 25 metres), now under St Nicholas Church and churchyard. This was the exercise hall or palaestra, where they could shop, exercise and socialise before heading into the bathing suite next door. The Jewry Wall probably formed part of the west side of this hall, and today stands 9 metres high, 2.5 metres wide and 23 metres long.

To enter the baths, people passed through arches in the Jewry Wall. There are two large arched openings at the centre of the wall, and further arched alcoves on the eastern side. The base of each arch is at Roman floor level.

The excavated remains of the bath suite itself lie between the Jewry Wall and the Jewry Wall Museum, and take the form of a series of stone foundations.

Roman bathing followed a specific process and would last anything from a few minutes to a few hours. Bathers first entered the cold room (frigidarium), off which there were changing rooms (apodyteria) and latrines. Once undressed, bathers walked back through the cold room into three warm rooms (tepidaria). Their floors were raised on pilae – stacks of stones or tiles – which allowed hot air to circulate beneath the floors, part of the hypocaust heating system. The bases of the pilae can still be seen.

Beyond these were three hot rooms (caldaria). The atmosphere in each was either dry like a modern sauna or wet and steamy. Semicircular hot plunge pools were positioned at the far, hottest end of the rooms right next to the furnaces, which powered the hypocaust. The foundations of the hot plunge pools and furnaces are now hidden beneath the Jewry Wall Museum.

On the north and south sides of the hot rooms there were also semicircular cold plunge pools.

Read more about Roman bathingLater history

In the Middle Ages the Roman baths were demolished so that both the stone and the space the buildings occupied could be reused. Only one fragment, the Jewry Wall, was left upstanding, perhaps because it may have been repurposed as part of an early Anglo-Saxon church or cathedral that was later destroyed. This rare type of reuse may in part explain why the wall has been so well preserved and may have ensured its survival when the adjacent St Nicholas Church was built.

How the wall came to be known as the ‘Jewry Wall’ is uncertain. Its name might derive from the 24 ‘Jurats’, or medieval borough councillors, who held meetings in the churchyard. In 1722 the antiquarian William Stukeley called it ‘The Jury Wall’ on his map of the town.

As the wall resembled a gateway, at this time it was commonly known as the Temple of Janus – Janus being the Roman god of gateways. It was thought to be the west gate of the town and was sometimes referred to as ‘the Janua of the old City’.

The modern spelling was in use in the early 19th century, but there is no known link to a Jewish quarter.

Discovery and excavations

The remains of the Roman baths were discovered in 1936 when a factory next to the wall was demolished to build, coincidentally, a new swimming baths.

The scale of the remains was so immense that on discovering them, the archaeologists initially thought they had found the town’s forum. They later realised that the Jewry Wall belonged to baths, in part because they found scorched matter that revealed the location of furnaces. Many artefacts were also recovered among the ruins, such as coins, pottery and bones, which helped to date the remains.

The excavations were led by the archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon (1906–78), who excavated here between 1936 and 1939. Kenyon had only been an archaeologist for six years when she undertook the excavations, which pioneered the investigation of Roman Leicester. Her work received funding from Leicester City Council, making it one of the first large-scale ‘rescue’ excavations in the country.

Because of the significance of the discoveries in the understanding of Romano-British urban development, the building plans were halted in favour of preservation. Jewry Wall Museum, which overlooks the site, opened in 1966 to preserve and display the archaeology to the wider public.

Read more about Kathleen Kenyon

Find out more

-

Visit the Jewry Wall

A length of Roman bath-house wall over 9 metres (30 feet) high, near a museum displaying the archaeology of Leicester and its region.

-

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan to see where the buildings of Roman Leicester were in relation to the city today.

-

Visit Jewry Wall Museum

Visit the Jewry Wall Museum, run by Leicester Museums and Galleries, to immerse yourself in the stories of Roman Leicester.

-

Roman Bathing

Read about Roman bathing and discover what Roman bath houses reveal about the culture and people of the time.

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.