The turf Wall

The original design for Hadrian’s Wall required a continuous ‘curtain’ wall and V-shaped ditch to run 80 Roman miles from Wallsend in the east to Burgh-by-Sands in the west. About 160 turrets were built two to every Roman mile (about 1.48km) along it, providing lookout positions for small groups of soldiers to monitor people’s movements, especially north of the Wall.

Pairs of turrets were positioned equidistantly between fortlets, known as milecastles, where garrisons of up to about 30 soldiers guarded gates that allowed travel through the Wall.

In the east and centre of the frontier, the wall was built from stone. In the west, however, for around 30 miles between the river Irthing near Harrows Scar Milecastle and Bowness-on-Solway on the coast, the Wall was originally built of turf, as it was probably easier and quicker to obtain from the surrounding landscape than stone. The turrets in this stretch of Wall – including Banks East – were built of stone from the outset.

After a few years the turf was replaced by a narrower stone Wall, which can be seen on both sides of the turret.

Turrets on Hadrian’s Wall

Turrets were typically about 6 metres square externally, recessed into the thickness of the Wall, and entered by a door in the south wall.

The full height and design of the turrets above the ground floor is uncertain. They may have had an open observation platform with a parapet, but in the damp conditions of northern Britannia they may have had pitched roofs, covered with tiles, thatch or shingles. The evidence differs from one turret to another, and roof construction may have varied over the centuries of occupation.

Using a numbering system introduced in 1930, milecastles are numbered 1 to 80 from east to west. Each pair of turrets take the same number as the nearest milecastle to their east, plus ‘a’ for the eastern turret and ‘b’ for the western one. Banks East is turret 52a.

The gods of Hadrian’s Wall

The Roman soldiers stationed along Hadrian’s Wall believed in the power of various deities and left plenty of evidence as to how they worshipped them. Romans sought the support of the gods via gifts, in the form of offerings. One popular type of offering was the purchase and dedication of an altar to a particular god.

This altar, found in a nearby milecastle, was probably made by soldiers stationed in this area. It reads:

To the god Cocidius, the soldiers of the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix, willingly and deservedly fulfilled their vow, when Apr[onius?] and Ruf[inus?] were consuls.

Cocidius was a Germanic war god, popular with the soldiers stationed on Hadrian’s Wall, who the soldiers had promised to please, presumably after they returned after a successful mission. The names of Roman consuls – the chief magistrates of Rome – provide a date of construction between AD 262 and 266.

Image © Historic England

The garrison

After the completion of the wall and its fortifications, soldiers recruited from non-citizens living all over the Roman Empire, known as auxiliaries, served as the Wall’s garrison. They were predominantly stationed at large forts, such as Birdoswald, in garrisons of 500 or 1,000, but the turrets provided shelter where small detachments of soldiers could cook, sleep and relax during the periods when they monitored the landscape or patrolled the Wall.

Excavations at Banks East Turret in 1933 recovered a mason’s hammer, a coin of Hadrian, pottery for cooking and eating, and several hearths. A rectangular stone platform against the north wall formed the base for a ladder that allowed the garrison to climb from the ground floor to the upper levels. The height of the turret was lowered in the 3rd century AD, creating a building with a lean-to roof ending at the height of the Wall.

Over the 350 years of the Wall, soldiers occupied some turrets continuously while they abandoned or adapted others according to changing military needs. Banks East remained in use into the later 4th century AD.

Discovery and excavation

The discovery and excavation of Banks East Turret, together with the two turrets at Piper Sike and Leahill, during the 1930s, were important steps in the process of understanding that the turf wall extended all the way to the west coast.

The archaeologist Frank Simpson was the first to establish this fact. He did so by initially finding and examining several turrets of ‘turf Wall type’ – free-standing stone towers against which Hadrian’s Wall abutted – west of Birdoswald. Turrets 51a and 51b (Piper Sike and Leahill) were two of those he recognised during trial excavations in 1927, but Banks East was the best preserved.

Because of this, it was excavated soon after its discovery, in 1933, and afterwards the road (under which its remains had mostly been buried) was diverted to skirt the turret so that it could remain on public display. This was the first section of Hadrian’s Wall to be taken into the guardianship of the Ministry of Works, a predecessor of English Heritage.

Hadrian’s Wall in the area

Banks East turret is the most westerly of a fine group of Hadrian’s Wall monuments centred on Birdoswald Roman Fort, just 3 miles to the east.

-

Visit Birdoswald Roman Fort

Birdoswald remained in occupation throughout the Roman period, and its defences are the best preserved of any along the Wall.

-

Visit Leahill and Piper Sike turrets

This pair of turrets, about 500 metres apart, were originally part of the sector of Hadrian’s Wall first built in turf and later replaced in stone.

-

Visit the Wall at Hare Hill

At Hare Hill, a short length of Hadrian’s Wall stands to a height of 3 metres – the highest part to survive along the entire length of the Wall.

-

Visit Pike Hill Signal Tower

The remains of one of a network of signal towers pre-dating Hadrian’s Wall, Pike Hill was later joined to the Wall at an angle of 45 degrees.

More about Hadrian’s Wall

-

Hadrian’s Wall: History and Stories

Discover the history and stories associated with Hadrian’s Wall, the north-western frontier of the Roman Empire.

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.

-

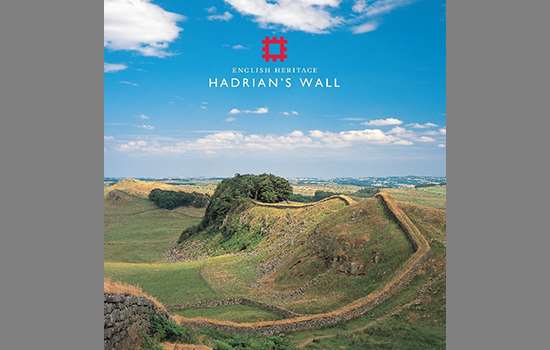

Buy the guidebook to Hadrian’s Wall

The English Heritage guidebook to the Wall provides maps, plans and tours of all the key sites, as well as a history of the Wall and its forts.

-

EXPLORE ROMAN BRITAIN

Browse our articles on the Romans to discover the impact and legacy of the Roman era on Britain’s landscape, buildings, life and culture.