Who Was Hadrian?

Publius Aelius Hadrianus (AD 76–138), known to us as Hadrian, was born in Rome on 24 January AD 76. His family – the Aelii – were from ltalica in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica (near Seville in modern-day Spain). Hadrian’s father died when he was only ten years old and he became the ward of his father’s cousin, the future emperor Trajan.

Trajan (r. AD 98–117) was an ambitious and aggressive emperor. Hadrian gained extensive military experience as a legatus (general) during the conquests of Dacia (modern-day Romania) and later Parthia (Iraq). As one of Trajan’s closest allies he also held the important offices of the Roman state, culminating in serving as consul – traditionally an executive role of the highest honour – and two terms as a governor of provinces of the Roman Empire.

Trajan died in AD 117 having not publicly named a successor. Hadrian’s extensive military experience and closeness to Trajan meant that he was an obvious and persuasive candidate. The day after Trajan’s death it was announced that Hadrian had been adopted as his son and heir before the emperor’s death, although there were rumours that Hadrian’s supporters had staged this.

However, with the army recognising Hadrian as emperor, the Roman senate – traditionally the highest decision-making body of the state – accepted his rule. Four senators who opposed his appointment were executed.

Why did Hadrian build the wall?

When Hadrian inherited the Roman Empire, it had been continually expanding for hundreds of years. It was beset with rebellions and struggling with the consequences of holding onto newly-won provinces. Hadrian therefore decided to implement a policy of security and stability within the empire’s existing boundaries.

He gave up some of the territory that Trajan had won in Dacia, and the lands won from Parthia to the east of the River Euphrates, and focused instead on reviewing his army and reforming military installations along the empire’s frontiers. Hadrian visited northern Germany, for example, where he inspected the army and updated the frontier to include Rome’s first artificial border – a continuous wooden palisade.

In Britain, which Hadrian visited in AD 122, the focus on shoring up the empire resulted in the construction of the famous Wall. The only Roman testimony on Hadrian’s intentions comes from a much later biography known as the Historia Augusta, which states simply that Hadrian ‘was the first to construct a wall … which was to separate the barbarians from the Romans.’

But this reveals little about the circumstances that led to the building of the Wall. There is some evidence to suggest that Britain was in revolt during Hadrian’s early reign and that the emperor mounted an expedition to suppress it. It’s possible that the Wall was a consequence, or even a cause, of the trouble. Whatever the intent behind it, the Wall was in keeping with Hadrian’s wider policy of frontier reform – but on the grandest of scales.

What did the Wall do?

The Wall was more elaborate than Hadrian’s frontier in Germany. A wide, tall curtain wall, mainly built of stone, ran continuously for 80 Roman miles (73 modern-day miles) from Wallsend in the east to Burgh-by-Sands in the west. It was wide enough for a wall walk for soldiers and had a deep ditch in front.

Prior to its construction, the northern frontier had consisted of a series of fortifications at strategic points linked by a road, known today as the Stanegate. Whereas the Stanegate allowed the Romans to monitor the landscape and respond to threats, the continuous and imposing new Wall served to stop unsanctioned movements through the frontier. It was also a strong deterrent and defence against raiding, the most likely threat to the province.

The Wall also facilitated controlled travel northwards and southwards. Every Roman mile there was a fortlet with a gateway, known as a milecastle, protected by a small garrison. Each one could monitor travellers or traders wishing to enter the province – perhaps levying taxes and checking for weapons. Initially, these small garrisons were intended to occupy the milecastles and pairs of towers (or turrets) positioned between each pair of milecastles. These watched the frontier and provided low-level security, but would have been little use against larger threats.

Shortly after construction began, the design was modified to accommodate 15 larger forts with garrisons of around 500 or 1,000 soldiers. This allowed more active monitoring of land to the north and formed a powerful force against substantial attacks. It also meant that the Wall was populated by a chain of communities, where soldiers, veterans and their families lived alongside traders and craftspeople.

Read more on the history of the wallLater life and reign

After his brief visit to Britain, Hadrian continued to tour the empire, returning to Spain and then to Asia, the Greek islands, Athens, Sicily and finally to Rome. Travelling was a constant feature of his reign, with later, lengthy tours of Africa and Mauretania, where he created another limes (border) to match those in Germania and Britain.

Back in Rome, Hadrian implemented the typical policies of a newly crowned emperor, revoking debts of citizens, paying for games and shows, and handing money to the people. Aside from the possible war in Britain, Hadrian’s only other major campaign was his bloody suppression of uprisings in the provinces of Cappadocia (Turkey) and Judaea (Palestine) in AD 132–5.

One of the enduring passions of Hadrian’s life was ancient Greek culture, earning him the nickname Graeculus (‘little Greek’) as a boy. Greece, though conquered by Rome, had a profound influence on Roman culture. As Emperor, Hadrian was keen to promote Hellenic culture, spending a year in Greece, particularly Athens. He adorned Athens with public buildings, including a new library and aqueduct, finished the vast temple of Olympian Zeus, and participated in religious festivals and rituals.

His commitment to reviving Greek culture was further expressed through the establishment of a Panhellenion – a commonwealth of Greek states through which the cities of Greece would heavily influence culture and practices across the eastern provinces of the empire.

Relationship with Antinous

Hadrian was married to Trajan’s great-niece Sabina Augusta, but he also had male lovers. It was common for Roman men, including many emperors, to have sexual relationships with other men alongside their marriage. While they would be classified by modern society as ‘bisexual’, the Romans did not define sexuality in such terms. They were defined through their sexual acts rather than their choice of sexual partners.

The most famous of Hadrian’s male lovers was a young Bithynian called Antinous, possibly a slave, who Hadrian met while on a visit to his home town. Antinous accompanied the emperor, along with his wife, Sabina, throughout the longest tour of his reign, culminating in a visit to Egypt, where they saw the tombs of Alexander the Great and enjoyed hunting together. But tragedy struck and Antinous drowned while sailing down the Nile in October AD 130. He was only about 20 years old.

Hadrian extravagantly commemorated the death of his lover. Near the spot where he died, Hadrian founded a new city named Antinoöpolis in his honour, and erected statues throughout the empire celebrating his youthful beauty. Most controversially, Hadrian had Antinous worshipped as a god – an unprecedented honour for anyone who was not a member of the imperial family.

Hadrian’s extreme response was ridiculed and provoked speculation about the manner of Antinous’ death. But the cult of Antinous proved popular, particularly in the eastern provinces of the empire. More images of Antinous survive than any other figure from the Roman world aside from Augustus and Hadrian himself. These were commonly reproduced during the early modern period and displayed in private homes, often as a subtle reference to homosexuality.

Death and legacy

Hadrian died of heart disease at Baiae (on the gulf of Naples) on 10 July AD 138 after a long reign that heavily impacted the culture and frontiers of the Roman Empire.

In Britain, Hadrian’s Wall was all but abandoned by his successor, Antoninus Pius, in favour of the new, more northerly Antonine Wall, between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. However, this wall was abandoned after the death of Antoninus, and Hadrian’s Wall was refurbished and reoccupied in the AD 160s. It remained the frontier of Roman Britain for a further 250 years, and has stood as Hadrian’s physical legacy for 1,900 years.

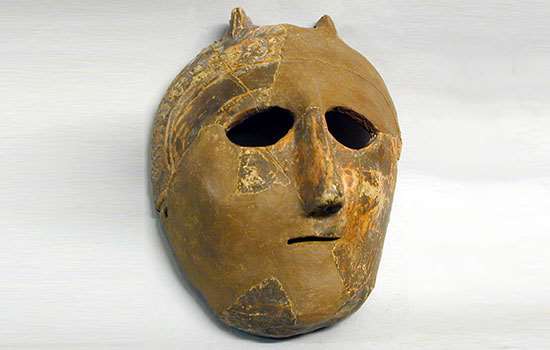

Top image: A bronze bust of Hadrian cast during his lifetime, showing him aged about 30 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Discover more

-

Listen to our Podcast

Learn more about Emperor Hadrian in this episode of our podcast featuring English Heritage Properties Historian Dr Andrew Roberts.

-

Hadrian’s Wall: History and Stories

Discover the histories, stories and and mysteries associated with English Heritage’s Hadrian’s Wall sites.

-

Septimius Severus

Learn about the Roman emperor who conducted brutal military campaigns in Parthia and Britain, and left a lasting mark on Hadrian’s Wall.

-

Cartimandua – Queen of the Brigantes

Ruler of the Brigantes, an Iron Age people of northern Britain, Cartimandua was an important ally of the Roman Empire during the conquest.