Early History

There is a much longer history to Brodsworth than the Victorian house and gardens might suggest. The house and village lie on a broad limestone ridge, a fertile area in which there have been settlements since the Iron Age. Running along the ridge is a major route north used by the Romans, whose garrison nearby developed to become Doncaster.[1]

Land farmed around the adjacent villages of Brodsworth and Pickburn was transferred into Norman ownership in 1086. A manor at Brodsworth was owned from the 12th to 16th centuries by the Darrell and Dawnay families. This was acquired by the Wentworth family in the 17th century, one of whom, Darcy Wentworth of Brodsworth, became embroiled in the Civil War on the Parliamentarian side.

The exact size and site of the manor house of this period are not known. It may have been incorporated into the 18th-century house near the church of St Michael and All Angels. Evidence of a deserted medieval village has also been found to the east of the church.[2]

Creating an 18th-Century Estate

The manor including ‘Brodsworth Hall’ was sold in 1713 by Sir John Wentworth to George Hay, Viscount Dupplin. After falling from political favour in 1715, Dupplin retreated to Brodsworth and probably rebuilt or improved the house. He is known to have laid out pleasure gardens and woodland walks, and planted trees across the estate.

Dupplin, who became the 8th Earl of Kinnoull in 1719, invested and traded heavily in stock of the South Sea Company, which had a monopoly over the supply of African slaves to the Spanish American colonies. But profit was limited, and Hay lost heavily when the price of stock rose rapidly and then plummeted during the South Sea Bubble speculation in 1720. Leaving his wife and many children at Brodsworth, he then spent most of his time in London, and served for a period (1729–36) as British ambassador in Constantinople.

After Kinnoull’s death in 1758 the Brodsworth estate became the home of the 9th Earl’s younger brother, Robert Hay Drummond, who from 1761 was Archbishop of York. He divided his energies between his archiepiscopal duties, building projects at Bishopthorpe Palace (just south of York), improving his childhood home and estate at Brodsworth, and entertaining there.

A ‘Spacious and noble mansion’

Archbishop Hay Drummond clearly had architectural ambitions, commissioning plans from Robert Adam between 1761 and 1765 for both a new house and alternatively adding to the existing house at Brodsworth.[3]

The architect of the scheme actually undertaken over the next ten years is not known, but it seems to have involved major rebuilding and refacing of the house. Photographs, maps and paintings record a huge house with canted bays at the centre of its main façades. A long 13-bay front overlooked the village and church, with short wings at each end reaching back to the stable block.

The archbishop did not enjoy his ‘spacious and noble mansion’[4] for long, dying in 1776. His eldest son became the 10th Earl of Kinnoull in 1787, inheriting Dupplin Castle and estates in Scotland, and put the Brodsworth estate up for sale once more.

Peter Thellusson and His Will

The Brodsworth estate was bought in 1791 by Peter Thellusson, drawing on funds accumulated from his trading and banking activities. He came from a family long established in European commerce. Originally French Huguenots (Protestants), they were later Swiss merchants and financiers.

Peter Thellusson settled in England in 1760, acting as an agent for the family and other banks. He amassed a huge fortune, part of which was linked to the transatlantic slave economy (see feature below). Like many people who made money in trade and finance, he was able to buy a place in landed society. He first commissioned a Palladian villa by Thomas Leverton at Plaistow, near Bromley in Kent, in the 1780s, before buying the substantial Brodsworth estate.

When he died in 1797 Thellusson left what has been described as one of the most spectacularly vindictive wills in British history. It left the bulk of his fortune in trust for as yet unborn descendants. The protracted legal battles between family members that followed – and from which the lawyers and trustees seemed to benefit most – may have been one of the examples that inspired the labyrinthine case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House.

Fears about the vast fortune which might be amassed also brought about the ‘Thellusson Act’ of 1800, which limited the time for which property could be left to accumulate.[5]

The Thellussons’ wealth

It is difficult to determine how much of Peter Thellusson’s wealth was derived from the transatlantic slave economy, but it was certainly a substantial part.

His involvement was wide-ranging. He lent money to slave traders and plantation owners; insured slaving ships and their cargoes; traded in beads used as currency in West Africa; and traded in goods such as sugar, coffee, tobacco and rum produced by enslaved workers on plantations in the Caribbean. In 1765 he invested with partners in the ship the Lottery, which transported enslaved Africans to Grenada, and in 1768 became temporary part-owner of several other slaving ships and their trafficked human cargoes, as payment for debt from slave traders who had borrowed from him. He also had a financial stake in several plantations in Grenada and Montserrat, acquired when creditors defaulted on their loans.

From the 1780s Thellusson consolidated his interest in sugar, the most valuable Caribbean commodity, by investing in several sugar refineries in London. His refinery investments alone were valued at £49,000 in 1796 (over £5 million in today’s money).[6]

The enslavement of Africans financially benefited British society on many levels, and Brodsworth is not unusual in having strong connections with the slave trade. Other Yorkshire houses such as Harewood also benefited from income generated through the slave economy.

Peter Thellusson’s own conclusion on his accumulated wealth, cited in his will of 1796, was that he had ‘earned the Fortune which I now possess with Industry and Honesty’.[7]

A Divided Inheritance

The effect of Peter Thellusson’s will for Brodsworth was that the estate was managed and enjoyed mainly by the trustees, probably with little investment in the house, for half a century. This may have been one of the reasons for the drastic changes undertaken by the next member of the Thellusson family to own Brodsworth.

After a legal judgment in 1858 the inheritance was finally divided the next year between two of Peter Thellusson’s great-grandsons. Frederick, 4th Lord Rendlesham, received an estate in Suffolk and remaining Caribbean property, while Charles Sabine Thellusson (1822–85) was granted the Brodsworth estate.

Charles Sabine Thellusson had grown up with an impecunious father but the great expectation of inheriting the Thellusson fortune. He spent a few years as a captain in the 12th Lancers, and in 1850 married Georgiana Theobald, whose grandfather John Theobald was a horse-racing friend of his father.

Theobald had made money in the hosiery trade, later building up one of the largest studs in the country at Stockwell, then south of London. The paintings of racehorses still at Brodsworth today were inherited from John and his son William Theobald.

Charles’s new-found wealth therefore originated both from his inheritance from his great-grandfather and from industry (his wife’s family’s hosiery business).

Brodsworth remodelled

Charles Sabine Thellusson was a leading yachtsman and enjoyed yachting on the south coast in the summer and shooting in the winter. The Thellussons required a house and estate suited to family life and entertaining their social set. They soon decided to replace entirely the massive Georgian house with a more efficiently planned new house, setting it further away from the church and village in private gardens overlooking newly opened up parkland.

Thellusson commissioned a London architect, Philip Wilkinson, to build the Italianate mansion at great speed between 1861 and 1863. The fashionable Old Bond Street firm Lapworths was appointed to furnish the interiors of the new Hall with the most luxurious materials, including scagliola, marble, mahogany, Morocco leather and silk. It had a subsidiary wing for the servants to live and work in, with a separate laundry and gas works.

By the end of the 1860s the Thellussons’ remodelling of Brodsworth was complete. The gardens had been fully laid out and the estate improved, with woods to provide good shooting and well designed new farm buildings and cottages.

Changing Times

After Charles Sabine Thellusson died in 1885 each of his four sons inherited Brodsworth in turn. With falling agricultural income, it became increasingly difficult to maintain the house, which remained relatively unchanged.

The third son, also called Charles, leased land to the Brodsworth Colliery Company to sink a pit on the estate in 1905, which brought some additional income. Charles and his wife, Constance, were able to entertain and live in some style, redecorating rooms and introducting electricity to the house in 1913. After Charles’s death in 1919 the last brother, Augustus, who lived in Kent, tended to stay at Brodsworth only for the winter shooting.

In 1931 Brodsworth was inherited by Charles Grant-Dalton, the son of Charles Sabine Thellusson’s daughter Constance. Charles, his wife, Sylvia, and their 12-year-old daughter, Pamela, came to live at Brodsworth. By this time the house and estate were badly in need of investment, but economic depression and death duties ruled that out. They made the Victorian house more habitable and manageable, however, with ever fewer servants, by closing some rooms, brightening others with a lick of plain paint, and introducing a few modernisations such as a lift and an Aga cooker.

Find out more about Brodsworth's DeclineSaving Brodsworth

After her husband’s death in 1952 Sylvia Grant-Dalton remained at the hall for over 30 years. Widowed for a second time in 1970, she lived alone at Brodsworth, with eventually only one member of staff, until her death in 1988.

Brodsworth then faced an uncertain future because Pamela, by then Mrs Williams, did not wish to take it on. But Brodsworth’s qualities and impending crisis had been brought to public attention by Mark Girouard, Ben Read and the Victorian Society.[8] A solution was reached in 1990 when Mrs Williams gave the house and gardens to English Heritage. Almost all the contents were bought by the National Heritage Memorial Fund and transferred to English Heritage, which undertook to open Brodsworth to the public.

Major work was required to make the house safe and bring the overgrown gardens under control before Brodsworth opened in 1995. Its stonework and leaking roof were repaired and new services installed. Inside it was decided to conserve the interiors as far as possible as they were found, to preserve both what had survived of its original schemes and the distinctive character Brodsworth had gained from its later history and inhabitants.

Find out more

-

Visit Brodsworth Hall

Victorian country house frozen in time and award-winning gardens

-

The Decline of Brodsworth Hall

How the precarious survival of Brodsworth’s interiors reflects the determination of its final owners to preserve an earlier lifestyle.

-

Description of Brodsworth Hall

The hall survives with many of its original contents, while the gardens have been restored to their 19th-century appearance.

-

Brodsworth Hall collection highlights

Many of the objects at Brodsworth Hall today were among its original furnishings in the 1860s. View some of the highlights.

-

Buy the guidebook

This souvenir guide contains a full tour of the house and includes a history of the Thellusson and Grant-Dalton families, illustrated with many family photos.

-

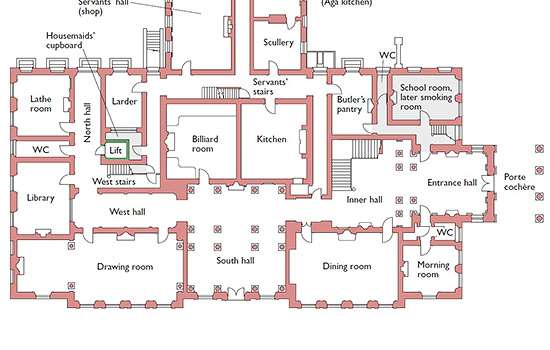

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan of Brodsworth Hall to explore in detail how this Victorian country house was laid out.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.