FRANKLIN, Benjamin (1706–1790)

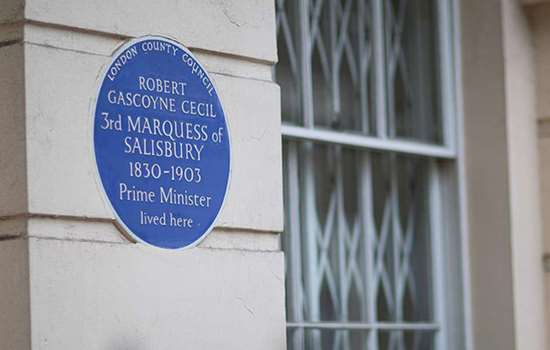

Plaque erected in 1914 by London County Council at 36 Craven Street, Charing Cross, London, WC2N 5NF, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Statesman, Scientist

Category

Journalism and Publishing, Politics and Administration, Science

Inscription

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (1706-1790) LIVED HERE

Material

Bronze

The writer and scientist Benjamin Franklin was one of the founding fathers of the United States of America. He spent many years in London and lodged at 36 Craven Street in 1757–62 and 1764–72, about a century before the construction of Charing Cross Station, which now dominates the street.

Early Years

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, to a family originally from Northamptonshire, Franklin trained as a printer and by the 1730s had become a highly successful writer and newspaperman in Philadelphia.

Meanwhile he developed his scientific interests, earning international acclaim for his work on electricity: he developed the concepts of ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ charge, and demonstrated by experiment that lightning was a form of electricity. Franklin was also responsible for many inventions, including the lightning conductor, a more efficient wood-burning stove and bifocal glasses.

Franklin also made contributions to meteorology and oceanography, notably by describing how the Gulf Stream worked. He showed too how different colours absorb different amounts of heat from the sun, and how metals vary in their thermal conductivity.

Franklin used the newspapers he published, notably the Pennsylvania Gazette, as an outlet for his reforming views. From the 1730s he condensed some of his ideals for living into homespun aphorisms for his bestselling annual Poor Richard’s Almanac. Having retired as a printer in 1748 he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1751; a critic of British colonial rule, he was an advocate for unity among the then-separate American states.

London Lodgings

It was diplomatic work that took Franklin to London for two vital periods: 1757–62 and 1764–75. During these years, as agent of the Pennsylvania Assembly, Franklin encouraged pro-American sympathies, continued his scientific experiments, mixed in circles that included James Boswell and Joseph Priestley and was active as a writer.

Franklin was amazed by the ‘dearness of living’ in the capital and in 1758 wrote to his wife:

The whole Town is one great smoaky House, and every Street a Chimney, the Air full of floating Sea Coal Soot.

Franklin’s years in London were spent at two addresses in Craven Street. His blue plaque can be found on the most significant of these, number 36 (then numbered 7), which was a lodging-house run by Margaret Stevenson. Here, in 1757–62 and 1764–72, Franklin occupied four comfortable rooms shared with his son and assistant, William (‘Billy’) – later Governor of New Jersey – and two enslaved men, Peter and King.

Peter, King and Franklin’s Attitude to Slavery

While Franklin was out of London, King fled the household. He joined the service of a lady in Suffolk, who taught him to read and write, and play the violin and French horn. Having tracked him down, Franklin agreed to sell King to the woman. He later wrote to his wife:

Peter continues with me, and behaves as well as I can expect in a country where there are many occasions of spoiling servants, if they are ever so good. He has as few faults as most of them [but I see them] with only one eye and hear with only one ear; so we rub on pretty comfortably.

Franklin owned enslaved people from about 1735 until 1781. In his household in America, he owned six slaves in total – Peter, his wife Jemima and their son Othello, George, John and King. Like most white Americans of his time, Franklin viewed black people as inferior, as he believed they couldn’t be educated.

However, in 1758 Samuel Johnson took him to one of Dr Bray’s London schools for black children, a philanthropic association affiliated to the Church of England. The following year Franklin donated money to the association, and after a later visit to a similar school in north America, recorded his new-found conviction that the ability and potential of the pupils was ‘in every respect equal to that of white children’.

Franklin also began openly to question the morality of slavery – though he did not free his own slaves for some time. In 1787 he became president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. He petitioned Congress in 1790 to provide the means to bring slavery an end and his last piece of writing before his death that year was a satirical attack on it.

Return to America

In October 1772 he – and Mrs Stevenson – moved to 1 Craven Street (now demolished), which was his home until his return to America three years later.

Following his return to Philadelphia, he became the leading spokesman for the American colonies and assisted in the preparation of the Declaration of Independence of 1776. He is the only one of the ‘Founding Fathers’ of the United States of America whose signature may be found not only on that document, but on the treaty that ended the War of Independence (1783) and on the new American Constitution (1787). He served as the United States’ Ambassador to France from 1776 until 1785 – the French finance minister said of him that he had 'snatched the lightning from the skies and the sceptre from the tyrants' – and then as President of Pennsylvania (1785–8).

He died on 17 April 1890, aged 84, and was buried at Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia.

Misplaced Plaque

Franklin was first commemorated in 1869 when the Society of Arts installed a plaque at 7 Craven Street. However, research carried out by Sir Laurence Gomme showed that this identification was incorrect: the number 7 in which Franklin had resided had later become number 36. The London County Council corrected the error in 1914 by mounting the bronze plaque now seen today. For a short time, until the demolition of number 7, the two plaques to Franklin rather embarrassingly stood on opposite sides of the street.

Number 36 has since been restored and was opened to the public as the Benjamin Franklin House on 17 January 2006, the 300th anniversary of his birth.

Further Reading

- The Benjamin Franklin House

- JA Leo Lemay, ‘Franklin, Benjamin (1706–1790)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) (public library subscription required)