DAVISON, Emily Wilding (1872–1913)

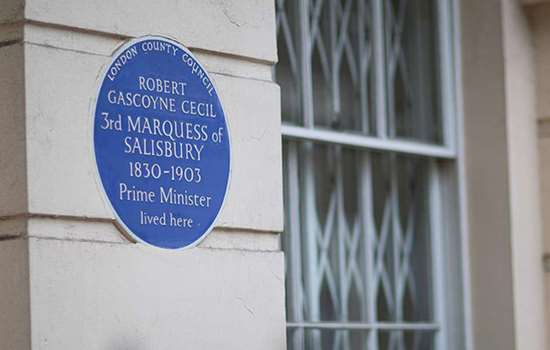

Plaque erected in 2023 by English Heritage at 43 Fairholme Road, West Kensington, London, W14 9JZ, London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Teacher

Category

Education, Philanthropy and Reform

Inscription

EMILY WILDING DAVISON 1872–1913 Teacher and Suffragette lived here

Material

Ceramic

Emily Wilding Davison, teacher and suffragette, campaigned boldly and tirelessly for women’s rights, even paying the ultimate price for her dedication to the cause. English Heritage has commemorated her with a blue plaque at 43 Fairholme Road, West Kensington, which was her home in the 1880s.

EARLY LIFE AND TEACHING CAREER

Emily Wilding Davison was born to Charles Edward Davison and his second wife, Margaret, née Caisley, on 11 October 1872, in Blackheath. Her early years were spent in a succession of impressive houses, large enough to accommodate her siblings and half-siblings, as well as servants and a governess. In 1885, Emily enrolled at Kensington High School. Six years later she left with a Higher Certificate of Education and a bursary to study English and mathematics at Holloway College.

In February 1893 Charles Davison died suddenly, leaving his family in difficult financial circumstances. Davison had to abandon her studies and her mother moved back to her home county of Northumberland to keep a shop in Longhorsley.

Following the death of her father, Davison worked as a governness. In 1895, she achieved first-class honours in English in the Oxford University examination for women but at that time women could not graduate from Oxford. From 1895 to 1898, she worked as a teacher and by 1901 she was employed as a governess. A gifted linguist, she continued to study alongside her work and in 1902 enrolled at the University of London, graduating in 1908 – by which time she was involved in the female suffrage campaign. She joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in November 1906 and the following year gave up her position as a governess to fully devote herself to suffragette activism.

SUFFRAGETTE ACTION AND PUNISHMENT

In March 1909, Davison was one of 21 suffragettes arrested when attempting to meet the prime minister, Herbert Asquith. She spent a month in prison. She was arrested again in July 1909 for disrupting a political meeting held by David Lloyd George. Back once more in Holloway Prison, Davison and her friend Mary Leigh protested against being denied the status of political prisoners and went on hunger strike. Davison was released after five days and recuperated at her mother’s house.

A bout of window-breaking in Radcliffe, Manchester, in October 1909 saw her imprisoned in Strangeways Prison, where she was forcibly fed. Her graphic account of this fuelled public debate about the legitimacy of the government’s brutal tactics. In April 1910 Davison became a paid worker for the WSPU, writing articles for its journal Votes for Women, and arguing the case for enfranchising women in letters to the newspapers. Later that year, after Asquith failed to deliver the Conciliation Bill – a bill which extended voting rights to women – Davison gained entrance to the House of Commons, where she broke the first of several windows, undeterred by the possibility of further imprisonment and force-feeding. On the night of the April 1911 census, she hid in a cupboard in the crypt under Westminster Hall as part of the census boycott.

UNILATERAL ACTION

By December 1911 Davison had stepped up her protests and, acting unilaterally, she set post boxes on fire by stuffing pieces of paraffin-soaked linen inside. At her trial in January 1912, she was sentenced to six months in Holloway, where she and fellow suffragettes endured solitary confinement and force-feeding. Davison recuperated in Longhorsley and by late November was arrested in Aberdeen and imprisoned, this time for mistaking a clergyman for Lloyd George and attacking him with a horse whip. By this point she was no longer on the WSPU payroll, whose leaders regarded her as a lone wolf. However, they continued to recognise her extraordinary resilience and in February 1913 she was sent an extra bar for her ‘Hunger Strike’ medal.

On Derby Day, 4 June 1913, Davison ran onto the Epsom racecourse and attempted to grab the bridle of Amner, a horse owned by George V. She was critically injured and died four days later. Davison was buried in the family plot at St Mary, Longhorsley, on 15 June.

HISTORICAL REPUTATION

Davison’s death made the news but it also divided opinion. The ambivalent response to her actions was apparent in the suffrage movement, as some feared her action would start a trend towards extremism and alienate public support. The suffragist Millicent Garrett Fawcett refrained from joining public mourning and the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies did not send a wreath to her funeral.

She remains a household name, and the question of whether her extreme act succeeded in furthering the aims of the suffragettes continues to be debated. There is also growing consensus that she did not set out to kill herself on Derby Day but simply wanted to pin the suffragette colours onto the king’s horse.

In the 1990s, the Labour MP Tony Benn put a plaque on the Palace of Westminster cupboard where she hid during the 1911 census. The 100th anniversary of Davison’s death was marked by publications, including a biography aimed at children, and commemorative events. Her grave remains a site of regular pilgrimage.

ADDRESS SELECTED

Number 43 Fairholme Road is the end property in an 1870s terrace, built as part of the Barons Court estate. It was while living here that Davison finished school and embarked on a course at Holloway College, only to have her plans dashed by severe financial hardship following her father’s death.

It seems that these experiences taught her resilience and made her determined to fulfil her potential. This was recognised by her former headmistress, Agnes Hitchcock, who recalled that whenever Davison visited her, ‘there was always the same bright look and happy, cheerful attitude towards life … I never heard her complain or express anxiety about her own future or that of her mother’ (Morley and Stanley, page 16).

FURTHER READING

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (public library subscription required)

- Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide (Abingdon, 2003)

- Lucy Fisher, Emily Wilding Davison: The Martyr Suffragette (London, 2018)

- A Morley and L Stanley, The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison (London, 1988)