DE GAULLE, General Charles (1890–1970)

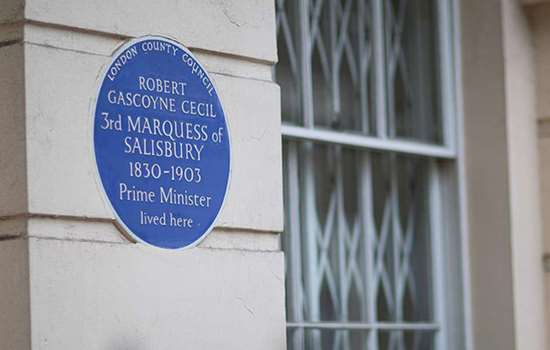

Plaque erected in 1984 by Greater London Council at 4 Carlton Gardens, St James’s, London, SW1Y 5AA, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Politician

Category

Armed Forces, Philanthropy and Reform

Inscription

GENERAL CHARLES DE GAULLE President of the French National Committee set up the Headquarters of the Free French Forces here in 1940

Material

Ceramic

During the Second World War, General Charles de Gaulle led France’s government-in-exile, the French National Committee, and set up the headquarters of the Free French Forces at 4 Carlton Gardens in St James’s in late July 1940. Later he was the founding force behind the Fifth Republic and served as the President of France for ten years.

Free France

Born in Lille, de Gaulle pursued a military career, and was promoted brigadier-general not long after the outbreak of the Second World War. He served briefly as Under-Secretary of State for War, but rebelled against the government led by Marshal Pétain – which sought a truce with Nazi Germany – and fled to London.

On 18 June 1940, the day after his arrival, de Gaulle used the BBC radio service – with the support of Winston Churchill – to deliver his famous address in which he encouraged his countrymen to continue to fight occupation. He concluded the broadcast with the words: ‘Whatever happens the flame of French resistance must not and shall not be extinguished.’

Sentenced to death in absentia by the Vichy government of Pétain, de Gaulle set about organising the so-called Free French Forces. It was a difficult start, marred by poor organisation, backbiting and a lack of experienced colleagues: ‘I have had to build all this up with matchsticks’, he later said. But by the end of 1944, the Free French Forces numbered one million individuals and played an important part in the liberation of France and in other theatres of the conflict.

De Gaulle achieved all this despite not being a particularly prominent figure when he first came to Britain. He had to overcome scepticism from many of his countrymen, and from elements in the British government too, with whom relations were not always smooth.

While in Britain, de Gaulle, his wife Yvonne and their three children first lived in a mock-Tudor villa in Petts Wood in south-east London. Later, the family moved to Shropshire and then Hertfordshire, where they were less vulnerable to bombing.

De Gaulle visited them when he could, but – when not on trips overseas – mostly remained in London, where he had a flat in Grosvenor Square. From September 1942 until the Free French HQ moved to Algiers in May 1943, the de Gaulle family were reunited in Frognal Lane, Hampstead, with the general sometimes overnighting at the Connaught Hotel in Mayfair.

Following liberation, de Gaulle became head of the French Provisional Government, and in 1958 he became the first President under France’s new Fifth Republic, a post he held until 1969. His period in office was notable for the war in Algeria that ended in that country’s independence in 1962 and for his withdrawal of France from NATO command structures in 1966.

Reputation

There is no doubt of de Gaulle’s vast influence in shaping modern France, and modern Europe too. His name became a political adjective (‘Gaullist’) and a party founded in this nationalist and broadly centrist tradition – the Rassemblement pour la République (RPR) – was a significant force in French politics for many years.

Twice de Gaulle vetoed British entry into the European Economic Community – the forerunner of the European Union. Some have linked this to the condescension shown to him at times during his London-based exile. He was not, for example, involved in the D-Day landing plans.

Carlton Gardens

Initially, it was intended that the plaque be placed on 3 Carlton Gardens, a building dating from around 1828 and which housed de Gaulle’s private office, where he slept on occasion. However, at the suggestion of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, it was placed on the neighbouring number 4, which housed most of the Free French departments.

The forces were associated with this building until mid-1944, though their headquarters moved to Algiers in 1943. Under the selection criteria, de Gaulle was not eligible for a blue plaque when the proposal was made in 1983, because he had died only 13 years earlier. However, it was deemed that because the plaque would commemorate the wider associations of the site as much as the individual, an exception could be made.

It was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother, in the presence of the French Ambassador and veterans of the Free French Forces on 5 June 1984, just hours before the 40th anniversary of the D-Day landings.

The blue plaque rests next to the rectangular tablet of black marble set up by the Free French of London to record de Gaulle’s rallying call of 18 June 1940. This, in turn, sits alongside the blue plaque to Lord Palmerston – ironically, the Prime Minister who is widely remembered for a costly set of coastal defences built some 80 years earlier to repel a phantom French invasion. A statue of de Gaulle also stands nearby.

Further Reading

-

Julian Jackson, A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle (2018)