AYRTON, Hertha (1854-1923)

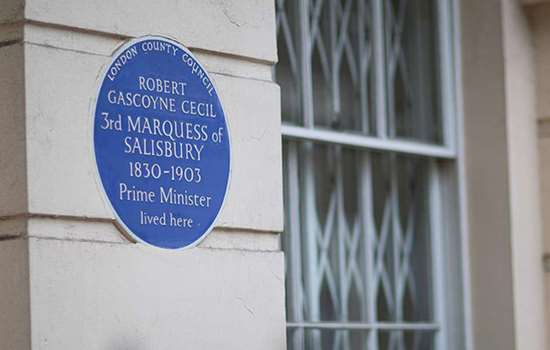

Plaque erected in 2007 by English Heritage at 41 Norfolk Square, Paddington, London, W2 1RX, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Physicist

Category

Science

Inscription

HERTHA AYRTON 1854-1923 Physicist lived here 1903-1923

Material

Ceramic

Hertha Ayrton was a pioneering physicist and promoter of women’s rights. She is best remembered for her work The Electric Arc (1902) and for the Ayrton fan, a device used in trench warfare for dispelling poisonous gases, which she invented while living at 41 Norfolk Square, just south of Paddington Station.

EARLY YEARS

Hertha Ayrton entered Girton College, Cambridge, in 1876 to read mathematics, having been given financial help by her friends Barbara Bodichon and George Eliot. Soon after leaving Girton in 1880, she patented a line divider (an engineering drawing instrument) and earned a living by teaching and embroidery.

Her first published articles appeared in The Electrician (1895–6), and were on the subject of the hissing of an electric arc, which she traced to the reaction of oxygen with carbon. In 1899 she read a paper on the subject to the Institution of Electrical Engineers, and became the first woman member of that body in the same year – the second was not admitted until 1958.

FAME AND PREJUDICE

In 1902 Hertha published her pioneering text, The Electric Arc, but was refused election to the Royal Society as the council found ‘it had no legal power to elect a married woman to this distinction’.

She did, however, become the first woman to read a paper to the Society in 1904, and to be awarded its Hughes Medal, which she received in 1906 for her work on the electric arc and on sand ripples. It was another 102 years before a woman won the medal again.

It may have been these experiences that prompted her to write to The Times, asserting the right of her acquaintance, Marie Curie, to be regarded as the sole discoverer of radium (the newspaper had awarded the credit to her husband).

THE AYRTON FAN

Hertha and her husband, William Ayrton, an electrical engineer, moved to 41 Norfolk Square – a four-storey terraced house built in the 1850s – in 1903. From 1905 to 1910, Hertha worked for the War Office and the Admiralty on standardising the types and sizes of carbons for searchlights, and filed patents in this area, as well as for arc lights.

When William died in 1908, Hertha moved her laboratory into the drawing room at number 41, and it was most likely there she developed the Ayrton fan (1915–18). Made of waterproof canvas and measuring 3 feet 6 inches long, it was a hand-operated device designed to disperse poisonous gases from the trenches during the First World War. Over 100,000 of them were used by British troops on the western front.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Ayrton was a noted supporter of women’s rights and of the suffragettes in particular. Her most significant role came during the operation of the notorious ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act of 1913, under which suffragette prisoners on hunger strike were released, only to be incarcerated again when they had sufficiently recovered. Some of the hunger strikers, including Emmeline Pankhurst, were cared for at her Norfolk Square home in 1913. During one of Mrs Pankhurst’s recuperative stays, Hertha wrote that:

There are two or more detectives in front, two at the back, one at least on the roof of the nearest empty house; and a taxi waiting to pursue, if Mrs P. should get up and run away!

Hertha Ayrton died at a friend’s house in Lancing, West Sussex, on 26 August 1923.