CLARK, Kenneth (1903–1983)

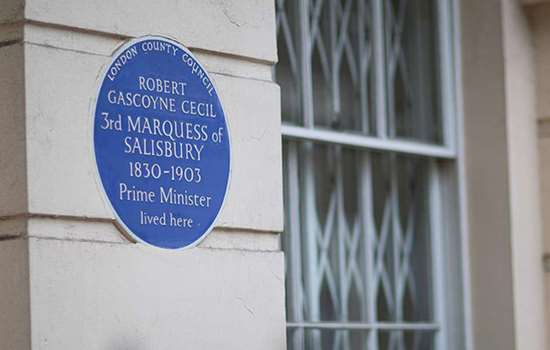

Plaque erected in 2021 by English Heritage at 30 Portland Place, Marylebone, London, W1B 1LZ, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Art historian and broadcaster

Category

Fine Arts, History and Biography, Radio and Television

Inscription

Sir KENNETH CLARK 1903–1983 Art historian and broadcaster lived here 1934–1939

Material

Ceramic

Kenneth Clark was one of the most influential British art historians of his era. For many years he was Director of the National Gallery, London, but he became most famous as the presenter of the TV series Civilisation (1969). His blue plaque marks his home at 30 Portland Place in Marylebone, where he lived from 1934 until 1939.

EARLY CAREER

Born into a wealthy family, Clark credited his education at Winchester College with helping to open ‘the doors of perception’. It was there that he read John Ruskin, whose work inspired his future career and encouraged his belief in the value of art for all. In 1922 Clark entered Trinity College, Oxford, to read Modern History, but the history and criticism of art soon emerged as his true passion. He stayed on at Oxford in 1925–6 to complete his first book, The Gothic Revival (1928), and during this time he also visited Italy, where he assisted the leading art critic Bernard Berenson in revising his influential book, The Drawings of the Florentine Painters (1903).

Clark married Jane Martin, whom he had met at Oxford, on 10 January 1927. After another trip to Italy for their honeymoon, the couple returned to London in time for the birth of their first child, Alan – later a Conservative MP and diarist. Two more children, the twins Colin and Collette, were born in 1932.

PORTLAND PLACE

The Clark family moved into 30 Portland Place in June 1934. It is part of a smart terrace of five large houses built in the late 18th century as part of the Adam brothers’ development on the Portland Estate. The Clarks furnished the Adam rooms ‘sparingly, at enormous cost’, but Clark’s busy London schedule meant he spent little time there. He wrote to Berenson that ‘I am hardly ever in [the house], but it makes a pleasant impression on me as I pass through it on the way from the front door to my bedroom.’

Among the Clarks’ good friends were John and Myfanwy Piper and Henry and Irina Moore. Marion Dorn and Ted McKnight Kauffer, Graham and Katherine Sutherland, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant were also regular dinner guests at Portland Place, and Clark commissioned many of them to produce art and furnishings for the house.

The Clarks hosted glittering parties at Portland Place, where guests included eminent people from the arts, politics and high society. This was the high point of what Clark later called ‘the Great Clark Boom’ of 1932–9. Towards the end of their residence, on 14 June 1939, the Clarks held a dinner for the American journalist Walter Lippmann, attended by Winston Churchill, Sybil Colefax, Harold Nicholson and Julian and Juliette Huxley. All agreed that they had witnessed ‘the most brilliant display of Churchill’s conversational powers’. Clark recalled that Churchill left in the early hours of the morning and told his chauffeur to take him to Chartwell, his home in Kent. ‘Good heavens,’ said Jane, ‘You’re not going all that way?’ To which Churchill replied, ‘Yes my dear, I only come to London to sock the Government or to dine with you.’

NATIONAL GALLERY

The same year that he moved into Portland Place, Clark became, at the age of 30, the youngest ever Director of the National Gallery. At the gallery he rehung the paintings, changed the lighting and extended opening hours until 8pm three nights a week. Between 1934 and 1939, visitors increased by 100,000. Privately, Clark sponsored several struggling artists who went on to become national and international figures – most notably Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and John Piper.

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Clark oversaw the removal of 800 of the gallery’s most valuable paintings to safety in north Wales, bringing back one picture a month to be shown to the public. With Dame Myra Hess he also organised popular lunchtime music recitals, which continued in the basement during the Blitz.

Clark briefly left the National Gallery in 1939 to make documentary films for the Ministry of Information, but returned in 1941. In 1946, after supervising the return of the paintings to London, Clark resigned permanently from the gallery to devote himself to his own research and writing. Between 1946 and 1950 he was Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford, where he became a brilliant and much sought-after lecturer. These lectures led to two important books, Landscape into Art (1949) and Piero della Francesca (1951).

CIVILISATION

Clark made over 60 television programmes in the 1950s and 1960s, including the series Is Art Necessary? for ATV, which ‘helped set the cultural agenda on British television’. His earlier experience at the Ministry of Information had taught him the value of film as a tool of mass communication, and he found that it allowed him to put into practice his belief in art’s public purpose and the importance of making it accessible to all.

In 1966 David Attenborough, then the controller of BBC2, invited Clark to lunch to discuss making a programme on ‘the history of all the great things man had created’, which would help promote colour television in the UK. They agreed on a 13-part series, to be written and presented by Clark, called Civilisation. The first episode was broadcast in February 1969, and the series proved to be a runaway success. For those without a television, each episode was published as an illustrated ‘narration’ in The Listener – later produced in book form as Civilisation (1969).

Although the press was generally enthusiastic, the series had its detractors. To some it seemed old-fashioned in content and delivery when compared with the new, more inclusive art history being championed on television by commentators such as John Berger. Clark’s view was Eurocentric, and he had little to say about the contribution of other cultures, or of women, to the arts and culture up to 1914. As Clark himself put it in a letter in 1970, Civilisation was ‘a kind of autobiography disguised as a summary of Western Civilisation’. Yet few could deny Civilisation’s impact. As well as bringing art and culture to a mass audience, it transformed cultural television, setting new standards for future arts documentary series.

Clark was made a life peer in 1969, becoming Lord Clark of Saltwood. He died aged 79, from arteriosclerosis, on 21 May 1983 at Hythe in Kent, and was buried in the parish churchyard.