Mass-Observation

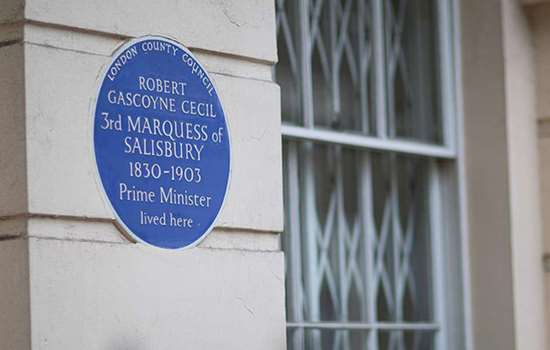

Plaque erected in 2022 by English Heritage at 6 Grotes Buildings, Blackheath, London, SE3 0QG, London Borough of Lewisham

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Pioneering social survey

Category

Economics and Statistics, Science

Inscription

The founding headquarters of MASS-OBSERVATION a pioneering social survey 1937–1939

Material

Ceramic

Mass-Observation, a pioneering social research organisation, is commemorated with a blue plaque at 6 Grotes Buildings, Blackheath. Charles Madge co-founded the project at his home here in 1937, and the location served as its headquarters until 1939.

Foundation

The main founders of Mass-Observation in 1937 were two Cambridge University drop-outs: Charles Madge (1912–96) and Tom Harrisson (1911–76); also involved at the outset was Humphrey Jennings (1907–50). In late 1936, around the time of Edward VIII’s abdication, Madge hosted a group of his intellectual friends at his Blackheath home, where they talked about the gulf between ‘public opinion’ as framed by newspapers – Madge himself was a Daily Mirror journalist – and what people actually thought and felt. Madge and Jennings, later famed as a documentary film maker, signed a letter that appeared in the New Statesman on 30 January 1937, inviting volunteers for a new research project, an ‘anthropology at home … a science of ourselves’.

Concurrently, Tom Harrisson – an anthropologist and ornithologist who had recently published an anthropology of Borneo and western Pacific islands – was poised to apply similar analyses to Britain and the British. He contacted Madge to suggest they join forces, and the pair set out to create a social anatomy of Britain using a two-pronged approach that reflected their respective backgrounds: behavioural observation in the field and collecting the diaries and questionnaire responses of volunteer observers.

By the end of the project’s first year, they had recruited 600 volunteer respondents and published, thanks to the support of TS Eliot at Faber and Faber, May 12th Mass-Observation Day-Survey – an account of popular responses to the coronation of George VI. They also tracked attitudes to the government policy of appeasement towards Hitler, discovering that 40 per cent of respondents admitted to not understanding foreign policy at all. Those behind Mass-Observation shared a belief that ‘don’t knows’ deserved to be treated as more than statistical detritus.

Women were well represented among Mass-Observation respondents and had an important presence on its staff too: the Austrian sociologist Gertrude Wagner prompted the examination of shopping habits in Bolton (partly achieved by following people around Woolworths). Her partner, Bill Naughton (1910–92), a co-op coalman turned autobiographical writer, was among the organisation’s working-class recruits. Other women who worked on the project included Celia Fremlin (1914–2009), who was later known as a writer of detective fiction, and Nina Mosel (1919–2004), who – as Nina Hibbin – became a film critic.

6 Grotes Buildings

Mass-Observation’s national operations, focusing on volunteer diaries and questionnaire responses, were directed from and sifted at Madge’s home at 6 Grotes Buildings, where he lived with the poet Kathleen Raine, and their young children Anna and James. The organisation also employed a few paid staff who worked from the house, alongside volunteers.

Dating from the late 18th century and Grade II listed, 6 Grotes Buildings was ‘the sort of house that one could become attached to’, wrote Madge. He and Raine were married in 1938, but both began affairs soon after – he with Inez Spender, wife of the poet Stephen.

Harrisson was initially based in Bolton (which the project called ‘Worktown’), Lancashire, where his team carried out behavioural observation of everything from the number of sugars taken in tea to the time it took for pub-goers to sink a pint of beer. In autumn 1938 Madge and Harrisson briefly swapped locations.

It was while headquartered in Blackheath that Mass-Observation compiled a key publication, the commercially successful Britain by Mass-Observation (1939), which features an essay by Madge on the Lambeth Walk dance craze and gives a unique glimpse of working-class life in London at the time. Other prominent projects included an interview-based investigation into anti-Semitism in the East End in 1939 and an observation of the West Fulham by-election in April 1938.

The headquarters remained at 6 Grotes Buildings until March 1939, then moved to Notting Hill, followed by a string of London addresses. The Second World War effectively ended the Worktown project in August 1940 but led to commissions from the Ministry of Information and the Admiralty, for which the organisation tracked public attitudes to the bombing – including the incidence of defeatism – and so helped to shape policy.

Madge was uncomfortable with the transformation of the organisation into what Harrisson called ‘a war-time listening machine’ for the government, and severed ties with Mass-Observation that year. It is, however, for its wartime work that the organisation is probably best known today.

The archive

After Harrisson left in 1949, the organisation became a market research company and was eventually incorporated into the British Market Research Bureau. In 1970 Harrisson lodged the Mass-Observation archive at the University of Sussex.

The project was relaunched in 1981 through diary and questionnaire response collecting, which continues to this day. In 2013 the archive was transferred to The Keep, a dedicated facility near Brighton.

By the Second World War, Mass-Observation’s panel consisted of some 2,000 respondents – 200 diaries survive from the early years of the war. The archive has become a much-used resource for social historians: Angus Calder’s The People’s War (1969) was early to mine it, as was Tom Harrisson’s Living Through the Blitz (1976). Several Mass-Observation diaries and histories have been published in recent years, as well as numerous articles.

Further reading

Hinton, J, The Mass Observers (Oxford, 2013)