FORTUNE, Robert (1812–1880)

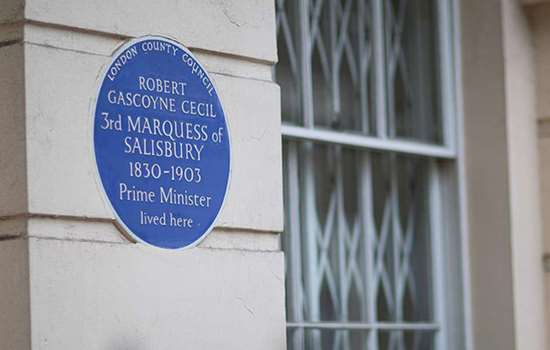

Plaque erected in 1998 by English Heritage at 9 Gilston Road, South Kensington, London, SW10 9SJ, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Botanist, Plant Collector

Category

Gardening, Science, Travel and Exploration

Inscription

ROBERT FORTUNE 1812-1880 Plant collector lived here 1857-1880

Material

Ceramic

Robert Fortune was a gardener, botanist and one of the earliest European plant collectors to visit China, introducing many plants new to Britain which are now commonly seen in English gardens. He is also remembered as the collector who took China’s tea plants and tea-making knowledge, introducing British-controlled tea production to India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), thus ending China’s monopoly. Fortune is commemorated with a blue plaque at 9 (formerly 1) Gilston Road, Kensington where he spent the last two decades of his life.

Gardener to Plant Collector

Robert Fortune was born in rural Berwickshire, Scotland. Fortune established himself as a skilled gardener and botanist, working his way up from an apprenticeship in the local gardens, to Edinburgh Botanical Garden, eventually to become superintendent of the Horticultural Society’s hothouse in Chiswick.

In 1843 Fortune made his first trip to China, tasked by the Horticultural Society with collecting both ornamental and useful plants and gathering information about Chinese horticulture and gardening. He spent three years there, exploring areas little known to foreigners and some that were forbidden to them. Fortune gained access to these areas by disguising himself in Chinese clothing and using his limited knowledge of local languages to present himself as a visitor from another part of China.

Thanks to the Wardian case – an innovative portable greenhouse which greatly increased the chances of bringing back plants alive from distant countries – Fortune introduced many of the plant he collected on his travels to Britain for the first time. This included the kumquat, the Japanese anemone and several species of azalea, rhododendron and chrysanthemum. He also collected orchids from Java and Manila during his travels.

Fortune’s journeys coincided with a growing interest in gardening amongst the upper and middle classes, and an increased demand for new, unknown garden plants from the ‘Orient’. At the time, the successful introduction and cultivation of plants outside of their country of origin was seen as a botanical triumph. Plant collectors were often honoured in a plant’s new European taxonomy. This used a binomial (two-word) system developed by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus and published in Systema Naturae (1735). The system used Latinised names to classify plants such as the Trachycarpus fortunei and Rhododendron fortunei, two Chinese plants named after Fortune.

The ‘Tea Thief’

After a spell as curator of the Chelsea Physic Garden (1846–8), Fortune set out for China once again, this time tasked by the East India Company with bringing back samples of the tea plant. In 1851 he introduced 2,000 plants and 17,000 sprouting seeds of tea into the North Western Provinces of India (then under Company rule). Fortune also brought back invaluable knowledge on the processes for manufacturing tea that he had secretly observed in China, including that green tea and black tea came from the same plant but were the result of different processes. European botanists gradually accepted Fortune’s reports, and the tea plant was given the Latinised botanic name Camellia sinensis, referring to its Chinese origins.

Fortune’s actions had far-reaching economic consequences: ending China’s monopoly of the industry, and enabling the British to take the lead on the lucrative production of tea in India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Tea imported from China had been expensive. Cheap tea grown under British control in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and India became a staple commodity in Britain. The element of espionage in Fortune’s work – and the sentiments of the Chinese about this – was made plain in the title of the 2002 film Robert Fortune: The Tea Thief.

Later life

From 1857 Fortune lived at Gilston Road in London, with his wife Jane and two children. The house, built by George Godwin, was almost new when they moved in.

Throughout his life, Fortune published several travelogues – lively accounts of his journeys to China and other parts of Asia which also included detailed insight into areas little known to Europeans. Works published while living at Gilston road include A Residence among the Chinese (1857) and Yeddo and Peking (1863) – his last work, which described his journey to China and Japan to collect tea shrubs and other plants on behalf of the United States patent office.

Fortune’s later years were blighted by illness associated with the adversities endured on his many travels. He died at this address, and is buried in nearby Brompton Cemetery.

Further reading

- G S Boulger, revised by Elizabeth Baigent, ‘Fortune, Robert (1812–1880), traveller and botanist’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2020) (access via UK public library card or subscription)