32 SOHO SQUARE

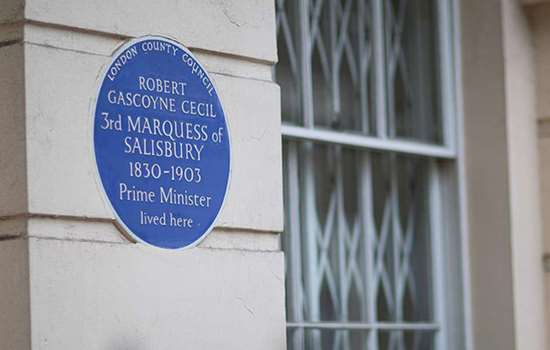

Plaque erected in 1938 by London County Council at 32 Soho Square, Soho, London, W1D 3AP, City of Westminster

All images © English Heritage

Profession

Botanists

Category

Historical Sites, Science

Inscription

SIR JOSEPH BANKS 1743-1820 PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY ROBERT BROWN 1773-1858 AND DAVID DON 1800-1841 BOTANISTS LIVED IN A HOUSE ON THIS SITE THE LINNEAN SOCIETY MET HERE 1821-1857

Material

Stone

Notes

The plaque is on rebuilt premises and replaces a blue LCC plaque of 1911 (to Sir Joseph Banks).

The botanists Sir Joseph Banks, Robert Brown and David Don are commemorated with an inscribed stone tablet at 31–32 Soho Square, the site of Banks’s former home, where the Linnean Society met. Banks was one of the most influential men of his time, at the forefront of scientific discovery for over half a century. Brown and Don were both distinguished botanists and librarians of the Linnean Society.

SIR JOSEPH BANKS (1743–1820)

Born in nearby Argyll Street, the son of a Lincolnshire landowner, Banks studied at Oxford before returning to the capital. He soon became a Fellow of both the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries. In 1766 he set sail as the naturalist on an expedition to Labrador and Newfoundland and from 1768 to 1771 he accompanied Captain Cook to the Pacific on the Endeavour. This second voyage was undertaken with the aim of observing the transit of Venus, but Banks and Cook also undertook to record any new territories, plants or resources that could be useful to the British Empire. It brought both men international acclaim, and Banks returned from the Pacific with unparalleled botanical and zoological knowledge.

Banks quickly established himself as one of the leaders of the British scientific community. He was President of the Royal Society from 1778 until his death, the longest-standing president on record. He formed a close friendship with George III and became a member of the Privy Council in 1797. Advising on scientific and agricultural policy, he had a direct impact on many affairs of state.

Banks became George III’s adviser for Kew Gardens, beginning its transformation from a royal pleasure garden into one of the world’s leading centres of botanical research and introducing thousands of exotic plants into Britain. He sent explorers and botanists all over the world looking for new and economically useful plants and animals. Species with particular economic significance were transported into and around the British Empire to establish lucrative colonial industries. From 1787, for example, Banks procured Merino sheep from Spain, which contributed to the stocks used to establish the Australian wool industry. Banks also helped arrange the transfer of breadfruit plants from the Pacific to the West Indies, where they were intended to provide cheap food for enslaved workers. This led to the failed mission of the Bounty (1787–9) and the successful subsequent mission of the Providence (1791–4), both captained by William Bligh, whom Banks recommended for the post.

Banks became particularly associated with the growing scientific knowledge of Australia. Encouraged by his experience during the Endeavour expedition, he urged the British government to support further exploration of the Pacific, notably Matthew Flinders’s circumnavigation of Australia (1801–3). He also advocated for the colonisation of Australia by the British.

Banks studied other cultures extensively, compiling vocabularies, for example, of the Tahitian language. His attitude to other races was typical of many Europeans of the time. Reflecting on the future of slavery in 1792, he suggested that black people had less ‘mental vigor’ than whites. His testimony to a parliamentary committee considering the establishment of a penal colony at Botany Bay proposed that the indigenous Australians were ‘cowardly’ and therefore unlikely to pose a threat to settlement.

Banks acquired 32 (then 30) Soho Square in 1777, and it was his London home for the rest of his life. Called ‘a virtual research institute’, it housed both his library and his extensive herbarium and other botanical collections. Banks lived there with his wife, Dorothea, née Hugessen (1758–1828), and his sister, Sarah (1744–1818), who was also a collector.

While living in Soho Square, Banks held frequent gatherings for, and corresponded with, an extensive and influential network of men of letters and of science from all over the globe. He had established an international community of scientists whose shared interests, he believed, transcended national ones.

Banks died in 1820 at his country home in Isleworth, now in south-west London.

ROBERT BROWN AND DAVID DON

Robert Brown (1773–1858), who first met Banks in about 1798, came to wider scientific attention as a naturalist on the Australian expedition led by Matthew Flinders in 1801–5. On his return, Brown was appointed librarian of the Linnean Society, and from 1810 was Sir Joseph Banks’s personal librarian at Soho Square. When Banks died, he bequeathed Brown a life interest in his collections, which subsequently passed to the British Museum.

From 1849 to 1853, Robert Brown served as President of the Linnean Society. He lived to the rear of number 32 at 17 Dean Street, where Banks’s library and collections were held. He stayed there until his death, by which time he had amassed one of the world’s greatest herbariums.

David Don (1799–1841) was born into a family of botanists and gardeners and succeeded Brown as librarian of the Linnean Society in 1822. He was later Professor of Botany at King’s College, London (1836–41), and died at number 32.

THE LINNEAN SOCIETY

The plaque’s inscription refers also to the Linnean Society of London, founded in 1788 by James Edward Smith (1759–1828), a friend of Sir Joseph Banks. The society was established for the study of natural history, and named in recognition of the pioneering Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, whose collections Smith had purchased on the encouragement of Banks. From summer 1822, Robert Brown sub-leased the front part of number 32 to the Linnean Society, formalising an arrangement under which the society had met at the house since May of the previous year.

The Soho Square house remained the society’s headquarters until 1857, when the Linnean Society moved to larger premises at Burlington House, Piccadilly.