You might think they’d be hard to miss, but giants are everywhere. We’re not talking about the cruel and destructive giants that you might expect, like Roald Dahl’s terrifying Fleshlumpeater. Instead, the mythical giants in England’s landscape are often closer to the BFG himself: builders rather than destroyers, and far more similar to us human beings than the monstrous giant stereotype. Far removed from fantasy and pantomime, legend places giants at several historical locations across the country and even attributes responsibility to them for some of England’s most iconic landmarks.

This year we’re taking a look at the myth, legend and folklore of England. In this blog, Mary Bateman, a doctoral researcher in the Department of English at the University of Bristol, explores giants through the country’s history; from rivers to ancient monuments. Is there truth behind the tale? We’ll leave that to you to decide.

The Early Days

Giants make appearances in stories all around the world, taking different forms but often sharing a variety of characteristics. In the ancient Mesopotamian poem The Epic of Gilgamesh, widely considered to be the earliest surviving work of literature, the eponymous hero battles Humbaba the Terrible, a lion-faced giant who guards the Cedar Forest where the Gods live. In Native American tradition, the red-headed Si-Te-Cah of Paiute lore are man-eaters, and the Nephilim of the Old Testament make normal men appear ‘as grasshoppers’.

Closer to home in Britain, giants present themselves in several pieces of folklore, from Ysbaddaden in the Welsh tradition, to enduringly popular English folktales such as Jack and the Beanstalk.

In Europe, including England, strange landscapes and man-made ruins or earthworks were frequently explained as the products of giants. The Old English poem The Ruin, written in the 8th or 9th century, seems to talk about the ruins of a Roman bathhouse as the construction of giants:

Wondrously wrought and fair its wall of stone,

Shattered by fate! The castles rent asunder,

The work of giants mouldered away!

[…]

Hot within,

The stream flowed with its mighty surge.

The wall surrounded all with its bright bosom.

The baths stood, hot within its heart …

Wrætlic is þes wealstan, wyrde gebræcon;

burgstede burston, brosnað enta geweorc.

[…]

stream hate wearp

widan wylme; weal eall befeng

beorhtan bosme, þær þa baþu wæron,

hat on hreþre.

Which place did this poet have in mind? Perhaps the ruined Wroxeter Roman City in Shropshire, as several scholars have suggested. Wroxeter was almost as large as Pompeii, and its beautifully preserved bathhouse and immense 7-metre basilica wall – the largest free-standing Roman wall in England – must have made an impression on the people who lived in the shadow of its ruins. It’s impossible to know for sure, but we know that large landscapes were often attributed to giants.

However, most scholars agree that the architectural detail in the poem can only point to one candidate: Bath in Somerset. This is particularly interesting given that nearby Stonehenge, England’s most iconic giant folklore site, also carries a story connected with bathing giants.

Stonehenge and bathing giants

According to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th-century History of the Kings of Britain, Stonehenge was originally brought from Africa to Mount Killaurus in Ireland by giants. Its magical stones had healing properties, and the giants built a bathhouse amid the stones to cure illness. Geoffrey suggests Merlin transported the stones from Ireland to their current location on Salisbury Plain at the behest of Aurelius Ambrosius to mark the graves of slaughtered British noblemen.

Quite how Merlin managed this is not made clear by Geoffrey, who states enigmatically that Merlin used his own ‘contrivances’ (machinationes) to transport the stones. However, an illustration in a 14th-century manuscript of the Brut, an adaptation of Geoffrey’s history, seems to show Merlin in the temporary form of a giant helping to reassemble the stones.

Big, friendly giants

The most prevailing image of the giant is a figure of violence and excess: for example, King Arthur is challenged by King Royns with his cloak made from kings’ beards in the English romance, the Alliterative Morte Arthure (circa 1400), and the man-eaters Blunderbore and Thunderdel of Jack the Giant Killer are equally unpleasant (1711). However, the giants of the English landscape subvert this monstrous stereotype, and can be remarkably human. They are lovers, spouses, friends, and brothers.

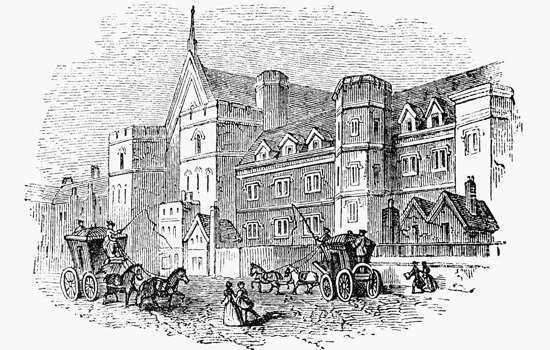

At Stokesay Castle in Shropshire, two well-heeled giant brothers are said to have lived either side of the valley in which the castle is situated – one on View Edge, the other at Norton Camp. They had shared stakes in a great hoard of treasure, which they kept in a vast oak chest-deep in the vaults of the castle. They had only one key between them, so whenever one brother needed to access the treasure they would toss the key to each other across the valley.

According to legend, one day, one of the brothers failed to aim properly, and the key fell into the dark depths of the castle moat, where it is said to lie to this day. The chest remains somewhere in the vaults, guarded by a giant raven who will not let anybody break it open without the key. These brothers, happy to share their riches with each other, are a far cry from the greedy or violent giant stereotype.

Giant causes

We find a similar story in Yorkshire. On Wheeldale Moor you will find a mile-long stretch of ancient road that snakes across the moorland, probably Roman but perhaps even earlier. The causeway, known as Wheeldale Roman Road, may extend even further than this, perhaps up to 25 miles. The striking monument is also known as Wade’s Causeway, after a giant named Wade (or ‘Wada’ in Old English). Wade is a common figure in Germanic mythology, first named in the 10th-century Anglo Saxon poem The Travellers Song as the ruler of the ‘Halsings’ (Haelsingum).

It is said that Wade built the causeway with his wife Bell, so that she could milk her huge cow on the moors; the boulders scattered across the landscape are said to have fallen from her apron as she went about building the road. In the 18th century, a whale’s jawbone was displayed as this cow’s rib in Mulgrave Castle, which Wade is also credited with building. Wade’s wife, Bell, was no less productive, and is said to have erected Pickering Castle nearby. While building the castle, legend says that Wade and Bell were limited for tools, having to share a massive hammer which they threw to each other to and fro over the hills. A model of marital bliss, Wade and Bell upend our negative preconceptions about giants, just like the two giant brothers of Stokesay.

A giant love story

To the south of Bristol, in the Avon Valley, we find the more tragic but no less humane love story of two giants, Goram and Vincent (or Ghyston in some tellings), whom some claim to be brothers. The earliest reference to a giant named Ghyst who once built a castle atop Ghyston Cliff (now Clifton) is William Worcester’s Topography of Medieval Bristol (1480). However the story did not reach its full form until its reworking by Bristol-based boy poet Thomas Chatterton in the late 1760s.

According to the tale, the giant brothers both fell in love with the beautiful giantess Avona, the river’s namesake. They competed for her love by trying to drain a lake, creating huge drainage channels which became the Avon Gorge and Hazel Brook in Henbury. Goram, heartbroken at losing the contest, stamped his foot in anger, creating the impression known as the Giant’s Footprint in Henbury gorge, before drowning himself in the Severn Estuary. The contours of his corpse became the two islands of Steepholm and Flatholm.

The Avon giants left their mark in other ways too. According to William Worcester in 1480, the figure of Ghyst was actually portrayed in the earth (in terra portraiatum), perhaps a turf-cut figure similar to the white giants at Cerne Abbas and Wilmington. Goram and Ghyst were not the only giants of north Somerset: in 1765, the antiquarian John Wood describes one ‘Hakill a Giant’, said by local people to have thrown a stone which became Hauteville’s Quoit, a standing stone near Stanton Drew stone circle. Wood reports that Hakill was so important a figure in local history that an effigy of him was maintained in the church at Chew Magna just over a mile away.

A hero of giant proportions

What conclusions can we draw about giants? At once human and inhumane, they represent our attempts to understand not only the landscapes around us, but also ourselves. They can be a reflection of everyday human life, or a manifestation of our darkest fears and desires. But perhaps most importantly of all, in their attachment to the ruins of past places, giants have also come to represent a kind of metaphor for the ravages of time itself, and of the impermanence of even the greatest and most ancient of beings.

Discover more myths and legends

England’s history is interwoven with the threads of myth, legend and folklore.

Visit our Telling Tales webpage to discover more about England’s past.

With your help we’ve also collected stories from across the country on our interactive online map. Visit our map to explore the stories.

More to explore

-

Secrets of our Sites

Join anthropologist and author Mary-Ann Ochota as she uncovers some of the hidden secrets of the world-famous English landmark, Stonehenge.

-

Obscure Medieval Laws

Historian William Eves explores law and order from the 13th century and highlights some of the more obscure rules — at least by modern standards.

-

English place names

Have you ever driven through a town and curiously pondered (or perhaps sniggered) over its name? Well, it turns out there's a story behind every one...