The medieval friary

Henry III (r.1216–72) gave the friars part of the site of the Norman castle of Gloucester, which had been vacant since the building of a new castle in the 12th century. Between 1241 and 1265 the king made many donations of money and oaks for timber to the first prior, William of Abingdon, to build his new church and cloister. He is reported to have reprimanded the prior:

Brother William, there was a time when you could speak of spiritual things; now all you can say is “Give, give, give”.

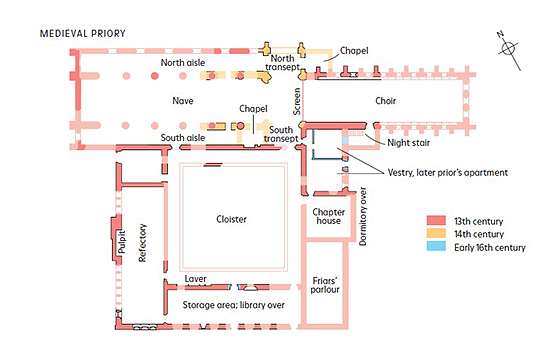

William’s persistent fundraising paid off, however, for in 1284 the Bishop of Worcester consecrated the completed church. Henry III’s son Edward I (r.1272–1307) granted more oaks in 1290 for further work on the cloister, and in the 1350s and 1360s the church was enlarged with transepts (side arms) and a central tower.

Several wealthy Gloucester townsmen granted tenements to the priory so that the friars could expand the monastic precinct around their buildings. By 1365 the priory occupied nearly 3 acres (1.2ha) between the town wall to the south-west, Southgate Street to the east and Longsmith Street to the north.

Who were the Dominican friars?

The Dominican order was founded in 1216 by St Dominic, a Spanish priest. In contrast to the monastic orders that pre-dated them, the orders of friars combined the enclosed life of monks with a mission to serve lay people. They lived in urban monasteries but they also went out into the town to preach, hear confessions and take part in funeral services.

There were several orders of friars, but the main two were the Dominicans and Franciscans. The new orders quickly spread throughout Europe from the 1220s. Friaries were mostly established in urban areas, complementing the existing system of parish churches in the fast-growing towns and cities of England. The English names of the friars described the cloaks they wore: the Dominicans were the black friars, and the Franciscans were the grey friars. While the black friars emphasised discipline and learning, the grey friars aspired to emulate Jesus as poor preachers.

In Gloucester the friars became an important part of the spiritual landscape. Local men and women left money to them in their wills, with some specifying that the friars take part in their funerals and others paying to be buried in the priory church or cemetery.

The friars did not own any personal property and early friaries were simple urban retreats. But the friars caught the popular imagination and donations poured in. Gradually, at Gloucester and elsewhere, they built large friaries, with grand churches and solid cloisters, just like the other monastic orders.

The friary buildings

The friars’ original church was long and narrow – over twice the length of the surviving building (73 metres compared to 32 metres). It was improved in the 14th century with a small tower and spire over the central crossing, and vaulted transepts on its north and south sides. The friars performed their church services in the choir at the east end of the church, while the nave or west end was large enough to accommodate the Gloucester townspeople who came to listen to the friars’ sermons.

Three other medieval buildings are laid out around the central courtyard or cloister. On the west side is the refectory or dining hall; on the south side is the library range; and on the east side part of the friars’ dormitory survives on the first floor.

The medieval friary was much larger than the surviving Blackfriars complex. The kitchen lay to the south of the refectory and there was probably an infirmary beside it for sick and elderly friars. Gardens provided food for the kitchen and medicinal plants for the infirmary. Friars and townspeople were buried in a cemetery now beneath the Ladybellegate Street car park, where in 1991 archaeologists excavated 128 burials of men, women and children.

Scroll through the images below to see some of the surviving features of the friary.

Closing the friary

The friaries could not escape the religious upheaval of the reign of Henry VIII, driven largely by his desire to divorce Katherine of Aragon and his need for money. In the 1530s he began closing England’s monasteries, nunneries and friaries, confiscating their rich assets for the Crown.

In about July 1538, one of the king’s commissioners from the Court of Augmentations, newly created to administer the confiscation of monastic lands and goods, visited Gloucester Blackfriars. Walking around the site he noted its fixtures and fittings – everything from alabaster altarpieces and two church bells to kitchen implements and the prior’s bedding.

The commissioner pressured the friars to close down voluntarily, and in August Prior John Reynolds and the six remaining friars signed a closure document, no doubt influenced by the prospect of a royal pension. Reynolds soon found another job as a priest at St Mary de Crypt, just opposite the priory on the other side of Southgate Street. Most of his friars found posts at other churches in Gloucestershire.

Tudor mansion and factory

The value of land in towns and cities means that few urban medieval monasteries have survived. Gloucester Blackfriars owes its partial survival to a Tudor merchant, and to the 20th-century Ministry of Works.

The Gloucester merchant and alderman Thomas Bell rented the Blackfriars site in 1538 and bought it the following year. Like hundreds of other new owners of former monasteries up and down the country, he set about converting the site into a mansion. He shortened the friars’ church and inserted upper floors and rooms in the nave and crossing. The church choir became his hall – also shorter, but still impressively tall and grand.

The prior’s apartment in the east range became Bell’s kitchen, handily placed so that servants could bring dishes to their master in the hall.

Bell’s wealth came from the woollen cloth industry and a cap-making business, and he converted the bulk of the cloister buildings to serve as warehouses and a factory. He was said to employ 300 people in the town. He served as mayor of Gloucester three times, was the city’s MP in the 1540s and was knighted in 1547.

Later history

In the 18th century the large Tudor mansion was split into two houses. Residents included the printer and newspaper proprietor Robert Raikes, who produced the Gloucester Journal here from 1743.

In the 19th century the warehouses in the former west range were converted into townhouses and workshops. From 1874 the Talbot Mineral Water Company’s factory occupied much of the east range initially, later extending into the south range. The factory continued to operate until 1954.

After the collapse of part of the east range in 1954, the Ministry of Works began purchasing the remains of the former friary to preserve the monument. From the 1960s it embarked on a programme of rather severe conservation and reconstruction, removing nearly all the 16th- to 19th-century interiors of the former church to create the Blackfriars site we see today.

Find out more

-

Visit Gloucester Blackfriars

One of the most complete surviving Dominican friaries in England, later converted into a Tudor house and cloth factory. Notable features include the church and fine scissor-braced dormitory roof.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of Gloucester Blackfriars to see how its buildings developed over time.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook provides a full history and tour of both Gloucester Blackfriars and nearby Greyfriars, with plans, reconstruction drawings and historic images.

-

WHAT BECAME OF THE MONKS AND NUNS AT THE DISSOLUTION?

Discover what happened to the many thousands of monks and nuns whose lives were changed forever when, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England was closed.

-

ABBEYS AND PRIORIES

Learn about England’s medieval monasteries and uncover the stories of those who lived, worked and prayed in them.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.