The borders

Etal Castle lies in north Northumberland, in England but close to the border with Scotland, and in an area that has long been known as the Borders. During the whole of the Middle Ages, this was a dangerous and lawless frontier region, prone to raiding and plundering by armed groups. Etal’s place in this story begins in the decade after 1100, when the new Norman overlords of England began to exert their control in the North.

The means of control was the creation of baronies – large tracts of land given to a powerful warrior lord to administer. Each barony was subdivided into manors, which were governed by knights loyal to their baron, while the resources of the land financed the system and enabled it to function and profit. In return, the baron and his knights routinely defended the border and gave military service to the king when larger expeditions were required.

In 1249, large buffer zones were created along the entire border by agreement between King Henry III (reigned 1216–72) of England and King Alexander III (reigned 1249–86) of Scotland. On both sides of the border these areas were called the East, Middle and West Marches, and each had a warden responsible to an overall Lord Warden in each country. A unique system of law, called March Law, was exercised to try to keep control and arbitrate in disputes. But despite this system, raiding, feuding and killing remained commonplace.

Etal and the Manners family

The manor of Etal lay within the barony of Wooler, created for Robert de Muschamp in 1107. The barony extended in a broad continuous block across Northumberland, from the Cheviot Hills in the west to the North Sea at Budle Bay in the east. By 1232 (and possibly 1180), Etal was owned by Robert Manners. His descendants continued to be lords of Etal throughout the Middle Ages, before exchanging it for land elsewhere and leaving the Borders in 1547.

The Manners were typical of the ruling border families. Important in regional affairs, they defended the border, launched raids across it, and negotiated peace when it was appropriate. Occasionally they were called to battle by the king, notably in 1346 when Sir Robert Manners took part in the Battle of Neville’s Cross, when a large invading Scottish army that had reached Durham was defeated.

A later Robert Manners was an associate of Henry Percy, 3rd Earl of Northumberland, and fought with him during the Wars of the Roses. Both were killed at the bloody Battle of Towton in 1461.

The Manners–Heron feud

Petty rivalry and feuding between families and their dependants were features of life in the Borders. In an atmosphere where violence, the destruction of property and theft were common during cross-border raids, power struggles between local families of the same nationality could also get out of hand.

In the early 15th century, John Manners became embroiled in a feud with the Heron family, who held the nearby manor of Ford. It resulted in a violent encounter in 1428. William Heron led an armed group to Etal, where fighting broke out. William and one of his men were killed, and John Manners was blamed and brought to trial.

John’s defence lay in the fact that William Heron had attacked Etal and that he personally was not responsible for William’s death. Although this was accepted, the law demanded that John should compensate William’s widow with a substantial sum and finance a priest to say 500 masses to pray for William’s soul.

Nevertheless, the feud continued, and only subsided when John Manners died in 1438.

Image: Ford Castle, seat of the Heron family at the time of the feud

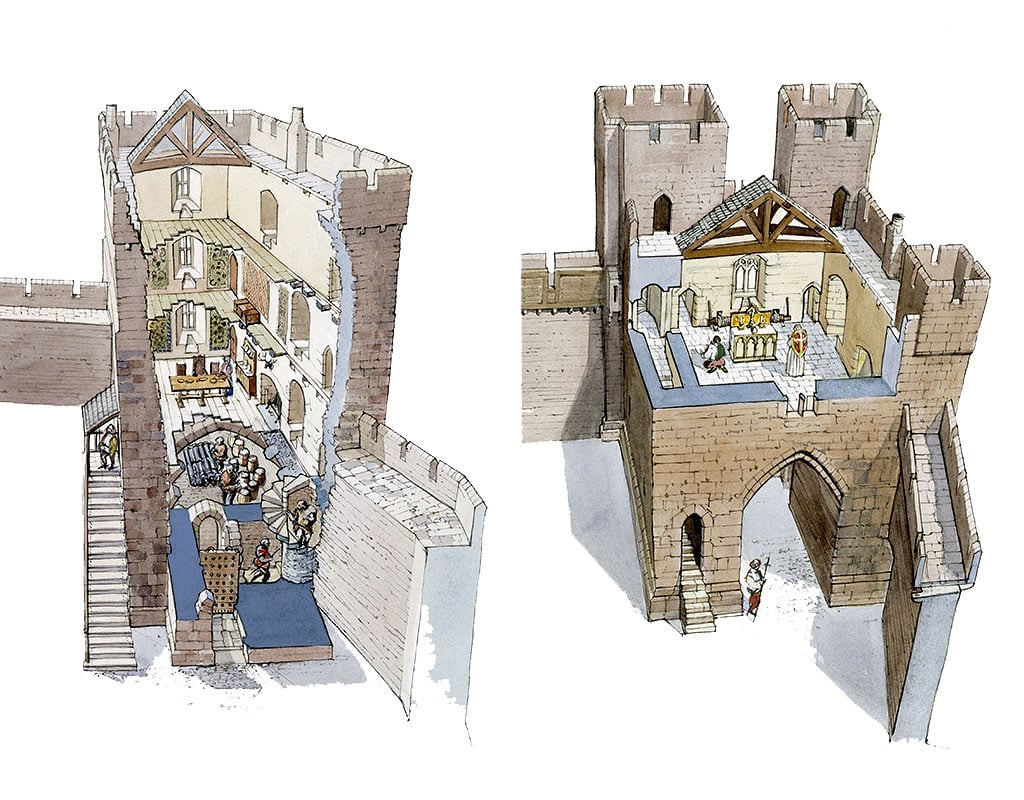

An impression of the castle’s appearance in the mid 14th century, showing the tower house (bottom left) and gatehouse at opposite corners of the rectangular, stone-walled enclosure, and towers at the other two corners. One of these towers has not survived. Other buildings such as stables, smithy, barns, stores and lodgings may have lined the walls

© Historic England (illustration by Terry Ball)

The castle’s development

Nothing is known about the manorial buildings at Etal in the 12th and 13th centuries. There may have been a timber-built hall and associated buildings, probably inside a defensible earthwork enclosure with a palisade, called a barmkin.

Significantly, Etal was described as a ‘fortalice’ (a minor fortification) in 1355 and as a castle in 1368. As King Edward III gave a ‘licence to crenellate’ (i.e. to build strong fortifications) in 1341, the period between 1341 and 1368 is probably when Etal developed into the small castle visible today, including the final form of the tower house, the gatehouse, stone walls and corner towers. As the top floor of the tower house is an addition to the lower storeys, the licence to crenellate may have enabled the strengthening of a building which had been erected before 1341.

This strengthening of Etal was the work of Sir Robert Manners and his son, John. When Sir Robert died in 1354, his assets at Etal included a corn mill, a fulling mill (for processing wool), lime kilns (for making mortar) and coal mines. He had also financed a chantry at Etal Chapel, where a priest was paid to pray for his soul.

The castle buildings

The gatehouse is two storeys high except in the flanking towers, which originally had three storeys. The gateway may have had a drawbridge and a projecting timber hoard (a fighting gallery), both long gone. Behind the drawbridge were a portcullis and the gate passage, where opposing doorways led into two guardrooms. The first floor had one large room which housed a winch for operating the drawbridge and portcullis, and may have doubled as a chapel, judging by the elaborate tracery of its windows.

The four-storey tower house, a strong building, contained the living accommodation of the lord’s family. Each floor was connected by a spiral staircase contained in a forebuilding, of which only the foundation survives. Its entrance had a portcullis. The ground floor contained a stout storeroom; the first floor was the hall where meals were eaten and business conducted; the second floor housed a private suite for the Manners family; and the third floor was possibly for the castle soldiers. Another entrance, added at first-floor level, had an external wooden stair to allow easier access to the hall.

Most of the castle’s curtain wall has gone, but a good stretch survives on the south side. It was intended as a deterrent to raiding parties, but was never strong enough to resist guns and would have crumbled under gunfire when cannon became common in the later 14th century. The garrison quickly surrendered to the Scottish army in 1513 (see below) for that reason. A high parapet walk, from which defenders could hurl missiles at attackers, was built on projecting stones along the wall.

The ground floor of the south-west corner tower survives, with a doorway leading into a vaulted ground-floor room.

The Battle of Flodden

Etal was a place of war during a Scots invasion of England in the summer of 1513. James IV (r.1488–1513) of Scotland brought a large army south of the border in support of his ally, Louis XII (r.1498–1515) of France. The English king, Henry VIII (r.1509–47), was in France fighting alongside the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I (r.1493–1519), in a long-standing conflict between the emperor and the king of France over ownership of lands in northern Italy.

Henry VIII had prepared for the possibility that the Scots might attack in support of their French allies. An English army, commanded by Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, marched to meet the Scots to give battle. The Scottish army had already crossed the border (defined by the river Tweed) and captured several castles, notably those at Norham, Ford and Etal. Etal was probably at least partially damaged during a brief bombardment.

After some manoeuvring to gain advantageous positions, the two large armies (the Scottish consisting of 30,000 to 40,000 men, the English 26,000) met on 9 September and fought a savage, bloody encounter near Branxton, about 4 miles from Etal. It was a crushing victory for the English. James IV and many of the great lords of Scotland were killed alongside an estimated 5,000–17,000 Scottish and 1,500 English soldiers.

In the aftermath of the battle, the impressive guns of the Scottish contingent were towed to Etal Castle and stored there temporarily, before being taken south to London.

Etal in the 16th century

In the early years of the 16th century, George Manners inherited the estate of the Ros family via his aunt, Isobel Lovell. As Lord Ros, he chose to live at Helmsley Castle in Yorkshire, leaving Etal Castle in the hands of a constable.

In 1535 the constable, Henry Collingwood, kept an active military force of 30 horsemen at Etal, but by 1541 the castle was in a state of disrepair. However, the Crown still regarded Etal as strategically important for the defence of the border and negotiated with the Manners family to take possession in exchange for land elsewhere. In 1547, the Manners sold Etal Castle to the Crown, after having owned it for over 300 years.

Under royal ownership, Etal continued to decline, despite occasional but important roles in continuing border troubles. For instance, in 1549, 100 horsemen and 200 infantry were at Etal during the War of the Rough Wooing (1543–51), another bitter conflict between England and Scotland. It began when Henry VIII tried to force a marriage between his son, Edward, and the infant Mary, Queen of Scots. Henry also wanted to weaken Scotland through a pre-emptive attack, to stop the Scots joining in the war he was fighting with the French.

The decline of Etal Castle

In 1603 the Crowns of England and Scotland were united in the person of James VI of Scotland (r.1567–1625) who became James I of England (r.1603–25). The need for a chain of fortresses along the border diminished, as raiding rapidly declined and warfare between the two countries was at an end. Etal Castle had lost its primary purpose and it became a neglected, old-fashioned place.

The Crown rented the castle to several families in the 17th century, probably more for the valuable land of the manor than for the castle as a residence. In 1636 a Scot, Robert Carr, bought the tenancy, and the castle then remained with the Carr family until the early 19th century. By this time, Etal Castle was an abandoned ruin, as the Carrs had built a modern, comfortable manor house at the opposite end of Etal village in 1748.

In 1908 Etal Castle was acquired by James Joicey, 1st Baron Joicey, a coal-mining magnate. Today, along with the Ford estate, Etal remains in the Joicey family. This joining of the former domains of the Manners and Heron families is a fitting, peaceful sequel to their medieval rivalries.

By Paul Pattison

Top image © Jim Gibson / Alamy Stock Photo

Related content

-

Visit Etal Castle

Etal was built in the mid 14th century by Robert Manners as a defence against Scots raiders, in a strategic position by a ford over the river Till.

-

Buy the guidebook

The guidebook gives a full tour and history of the site, and is richly illustrated with historical images, maps, plans and photographs.

-

History of Norham Castle

Nearby Norham was one of the great English strongholds along the river Tweed, a barrier against the Scots, who besieged it nine times, capturing it on four occasions.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.