Foundation

The priory was founded by Robert de Vaux, whose family had been granted the barony of Gilsland, on the border with Scotland, as reward for their part in the Norman Conquest. The area had only come under English rule in 1157. The founding of a priory was a symbol of Robert’s permanence in the area and of his wealth, as well as an act of piety. He gave the priory considerable lands and churches nearby, and allowed the canons the freedom to elect their own lord prior.

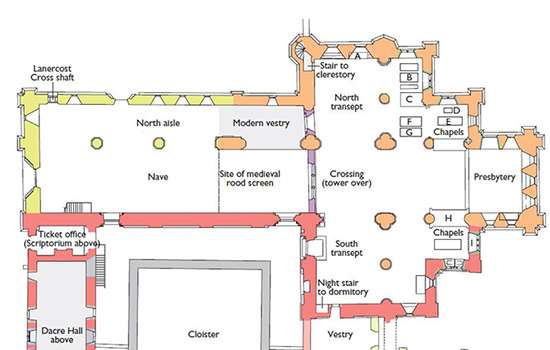

The earliest buildings were the south transept and south wall of the church, and the monastic buildings around the cloister. An inscribed cross, the base of which still stands in the outer precinct, with the upper shaft preserved in the church, was erected to mark the completion of this stage in 1214.

Building work then appears to have ceased for several decades, with the presbytery and north transept not built until about 1260. While the south transept has taller arches and a single window level (clerestory) above, the north transept has much sturdier, shorter pillars, supporting two levels of windows (triforium and clerestory) and a stone-vaulted roof.

Move the sliding bar to compare a reconstruction of Lanercost Priory as it may have looked in about 1280, when building of the church was almost complete, with a similar view today. (Illustration by Peter Urmston © Historic England)

Life at the priory

There were never more than 12–15 canons living at Lanercost, who combined monastic life with pastoral care of local people and nearby churches. Following the Rule of St Augustine and wearing black habits (cloaks), the canons would have prayed to God in the church seven times each day, on behalf of the founder, his family and their descendants. The priory was dedicated to St Mary Magdalene, whose statue adorns the west front of the church. At some point it acquired a relic, said to be a piece of the belt or girdle of St Mary Magdalene, which would have attracted pilgrims.

The priory buildings that survive today are only a small part of the monastic complex. It would have included a brewhouse, tannery, malt kiln, hay store, fishponds and a granary, as well as stables and other buildings for sheep, cattle and pigs. The entire precinct was surrounded by a wall, which still survives in places, with a single gatehouse containing a porter’s lodge.

The canons were supported by a substantial number of staff, including bailiffs who administered the estates, a butler, a caterer, a cook, a fisherman and a mason, as well as two ‘clerks of the choir’, employed to help in the singing of services. In 1537 a total of 40 people worked at the priory.

The Lanercost Cartulary

For the first 120 years of the priory’s existence the border with Scotland was relatively peaceful and the priory flourished. The only difficulties faced by the canons were arguments with their own patrons. Robert de Vaux’s great-niece Matilda had married Thomas de Multon, who disputed the ownership of certain priory lands. In 1258 and 1261 he even occupied the monastic buildings, leading the Bishop of Carlisle to appeal to the king for help in evicting him.

Evidently bruised by these early challenges, the canons began diligently to record exactly how their estate had been acquired and who had given them land, noting any disputes. This important archive, known as the Lanercost Cartulary, was updated by the canons until 1364 and survives today in the Carlisle Archive Centre. It is an extraordinary document, giving a detailed insight into the workings and history of the priory.

Image: A 14th-century drawing in the margin of the Lanercost Cartulary, depicting Lanercost Priory church with a tall spire

© Cumbria Archive Service (Carlisle Archive Centre) (ref DZ/1/1V)

Attacks by the Scots

The ambitions of King Edward I (reigned 1272–1307) to rule over Scotland were brought to a head when a Scottish alliance with France led to war in 1296. Monasteries on both sides of the border were exposed to attack. Lanercost suffered initially in April 1296, when the Scots encamped there and set fire to some of the monastic buildings. Late the following year the Scottish army led by William Wallace led raids into northern England and the priory was attacked again.

There was worse to come. In 1311 a force led by Robert Bruce, King of Scotland (r.1306–29), descended on the priory and stayed for three days, ‘doing an infinity of injury’ and imprisoning the canons. The priory lands were repeatedly devastated during such incursions, and in 1318 the estates, once valued at nearly £75 a year, were found to be worthless and totally destroyed.

The priory was besieged again and ransacked in October 1346 by the Scottish army of King David II (r.1329–71). ‘They entered arrogantly into the sanctuary, threw out the vessels of the temple, plundered the treasury, shattered the bones, stole the jewels and destroyed as much as they could’, a contemporary chronicler wrote. These raids left Lanercost Priory with buildings to repair, valuable items to replace, stores pillaged and lands ravaged.

A Royal Imposition

Over five months in 1306–7, Lanercost temporarily became a royal residence and centre of national affairs. The elderly and unwell Edward I could no longer lead his army against the Scots, but was following them closely. In September 1306, unable to ride, he was carried on a litter from Newcastle, intending to hold a parliament at Carlisle. Resting at Lanercost, he became gravely ill and was forced to stay the winter at the priory.

The king had arrived with his retinue of around 200 people, including Queen Margaret, his eldest son, Prince Edward, and various nobles, servants, doctors and bodyguards. All had to be accommodated by the impoverished priory. Many lived in tents within the precinct, but buildings were quickly erected to provide accommodation for the royal party, including a separate chapel and bathhouse for the queen. Agents of the king were constantly arriving with messages, food and medicine, and paupers flocked to the priory gate in the hope of receiving alms. On one occasion, soldiers brought the severed heads of Scottish rebels to the king.

The crowding, disruption and noise would have been a huge imposition on the canons, who must have been greatly relieved when the king finally departed in March 1307.

Image: The remains of the cloister, where King Edward I probably took exercise, as he requested repairs to the guttering during his stay

Dissolution

The royal visit and repeated Scottish raids had left the priory greatly impoverished. Despite the king granting them the revenues from two additional churches, the priory was destitute and had to sell off much of its land. A tax return in 1379 recorded only a prior and four canons living there – probably all that its revenues could support – and in 1409 the priory appealed for help as the canons were ‘reduced to a low state and almost utter want’.

Help eventually came from their patrons, the Dacres. In 1487 Sir Thomas Dacre (1467–1525) married Elizabeth Greystoke, heiress to the barony of Greystoke and to many other estates in northern England. This marriage made him rich, enabling him to support the priory, which was close to the family home at Naworth Castle, with lands and money.

Even so, the priory remained poor. By the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries – the process whereby Henry VIII and his ministers closed down religious houses and seized their assets – its income was only £80 a year. As one of the smaller religious houses it was one of the first to be targeted, and it was closed in March 1537. At this time it was staffed by eight canons under the prior, together with the curate of the parish church and 40 lay staff.

The cloister and refectory were stripped of their roofs, and the monastic buildings were mostly left to ruin.

Conversion

After service at the Battle of Solway Moss in 1542, Thomas Dacre, an illegitimate son of Sir Thomas, was rewarded by Henry VIII with the priory and lands at Lanercost. He decided to convert the west cloister range into a private dwelling. On the first floor he built a 30-metre-long great hall with large windows and a magnificent fireplace, now known as Dacre Hall.

Around 1560 Thomas commissioned some fine wall paintings to decorate his new family home. A huge coat of arms dominated the north wall of the great hall, and in the room adjoining is an early 17th-century plaster frieze with heraldic shields painted with silver scallops, the arms of the Dacre family.

The east window of the church now contains some fragments of 16th-century glass which were removed from Dacre Hall. One of them carries a Latin inscription recording work there by Sir Thomas Dacre in 1559.

Dacre Hall is not generally open to the public, but is accessible during community events.

Family tombs

Like most monasteries, Lanercost served as a mausoleum for its founders and their successors – members of the Vaux, Multon, Dacre and Howard families. Many of their tombs still stand in the roofless eastern end of the church.

The oldest known tomb, with fragments of an effigy, belongs to Roland de Vaux, illegitimate son of the nephew of Robert, the priory’s founder, who died in 1199. In the south transept is the elaborate early 16th-century tomb of Sir Thomas Dacre and his wife, Elizabeth Greystoke. In the north transept chapel is the tomb of his parents, Humphrey Dacre and Mabel Parr, carved with heraldry displaying the arms of their respective families.

There were few family burials in the later 16th to 18th centuries but the Howard family, who purchased Lanercost from the Crown in 1869, revived the tradition. George Howard, 9th Earl of Carlisle, had his parents, Charles and Mary, buried here, as well as his son Christopher and infant daughter Elizabeth, who died in 1883. She is commemorated by a terracotta sculpture of a sleeping infant by Sir Edgar Boehm. The gravestones of George himself and his wife, Rosalind, are set in the floor.

Read more about the tombsRestoration and later

During the Civil War in the 1640s the Royalist Dacre family suffered financially. When James, the last of the family line, died in 1716, he had large debts and the property was returned to the Crown.

By this time the estates of the main branch of the Dacre family had descended to the Howards by marriage. Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle, encouraged the restoration of the church, which was completed by 1747. This work was done cheaply, however, and only 100 years later the church was again in a state of decay. After the roof collapsed, the architect Anthony Salvin, who was already working at Naworth Castle, was brought in to oversee restoration work, financed by the Crown, and the church reopened in 1849.

In 1869 George Howard, 9th Earl of Carlisle, bought the priory buildings from the Crown and carried out further works, installing the barrel-vaulted ceiling and a new organ in the church. George was a talented painter and had many artistic friends, who contributed to the restoration. Edward Burne-Jones made a bronze relief of the nativity, and William Morris designed the ‘dossal’ – an embroidered cloth panel to hang behind the altar. The two artists collaborated on stained glass windows.

By the early 20th century the cost of maintaining the priory ruins had become a burden to the Howard family, who entrusted them to the Office of Works in 1930, a precursor to English Heritage. An extended campaign of conservation and excavation followed, during which the remains of the first chapter house were revealed. In 1952 the family gave Dacre Hall to the local community, while the priory church of St Mary Magdalene remains in use as the parish church.

Further reading

H Maxwell (trans), The Chronicle of Lanercost, 1272–1346 (Glasgow, 1913; reprinted Burnham-on-Sea, 2001) (accessed 30 July 2020)

E Searle, ‘Housed in abbeys: the Dacres of Cumberland and Sussex, part I: the early Dacres and Lanercost Priory’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 57:2 (1994), 153–65 (subscription required; accessed 30 July 2020)

H Summerson and S Harrison, Lanercost Priory, Cumbria: A Survey and Documentary History, Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Research Series 10 (Kendal, 2000)

JM Todd (ed), The Lanercost Cartulary, Surtees Society 203 (Durham, 1997)

Find out more

-

Visit Lanercost Priory

An impressive and now-tranquil priory, once in the Anglo-Scottish firing line.

-

A Family Mausoleum

Like most monasteries, Lanercost served as a mausoleum for its founders, their successors and their families. Learn more about their tombs and explore some of them in 3D.

-

WHAT BECAME OF THE MONKS AND NUNS AT THE DISSOLUTION?

Discover what happened to the many thousands of monks and nuns whose lives were changed forever when, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England was closed.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan of Lanercost Priory to discover how its buildings have developed over time.

-

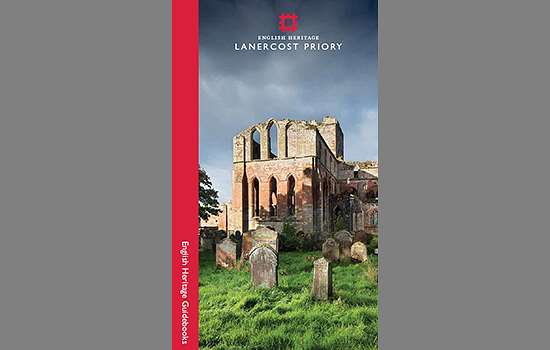

Buy the guidebook

This new guidebook includes a full tour of the priory buildings and the church and tells the story of the priory over 850 years.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.