Find out more

-

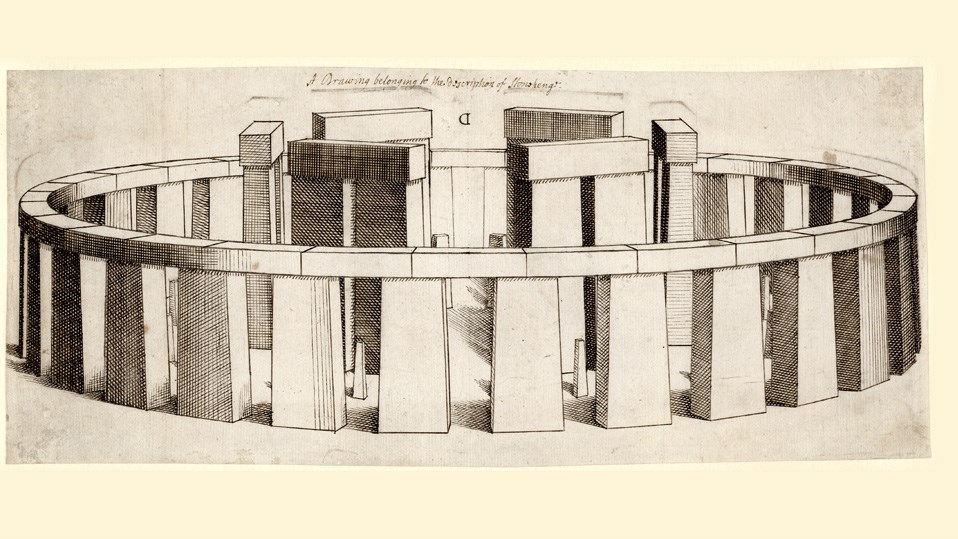

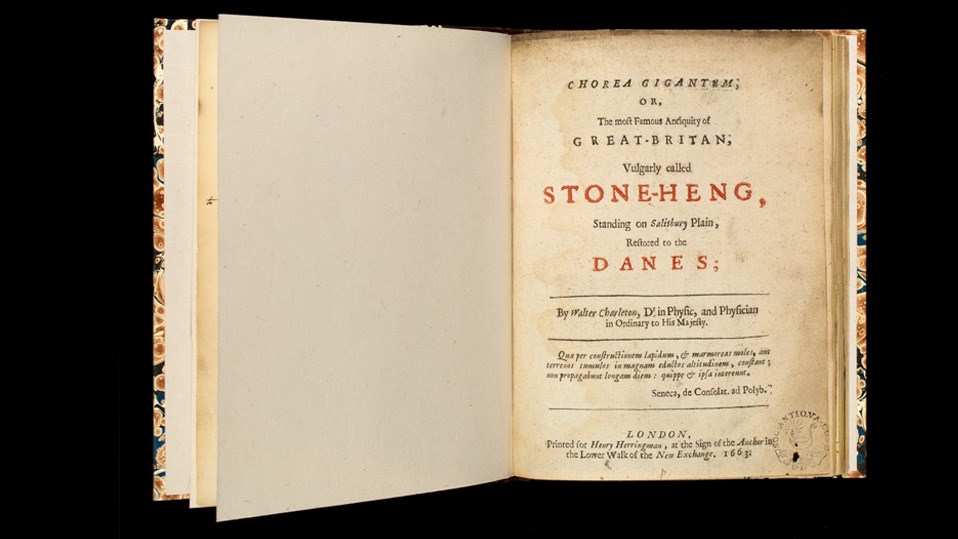

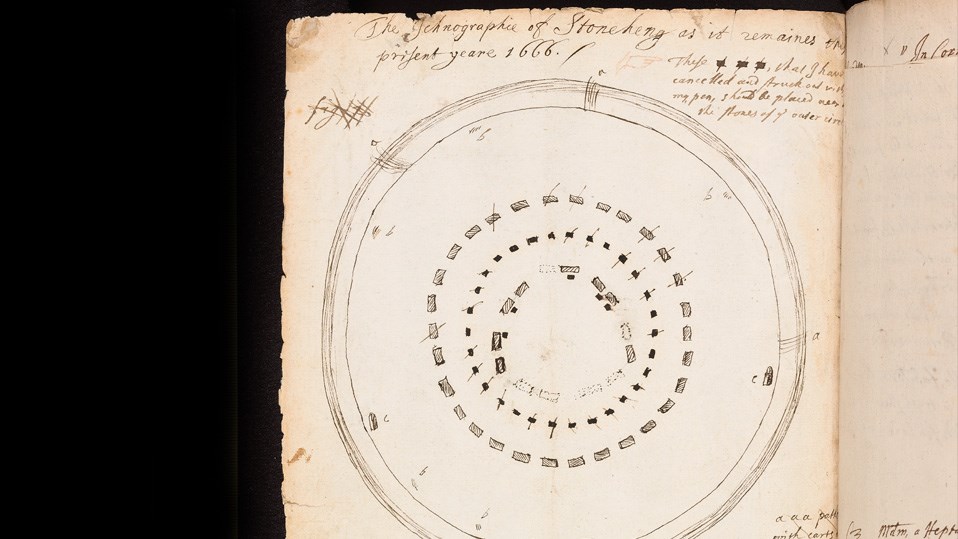

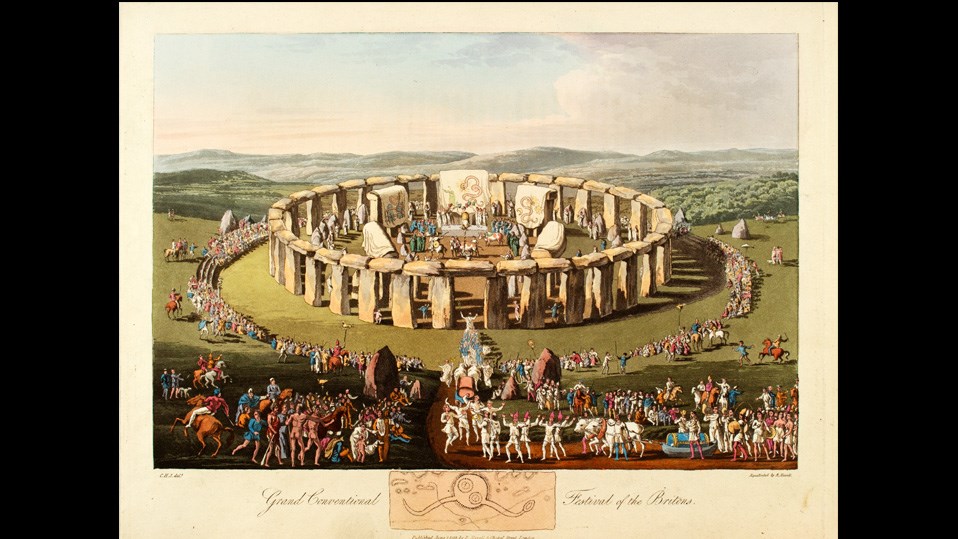

History of Stonehenge

Read a full history of one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments, from its origins about 5,000 years ago to the 21st century.

-

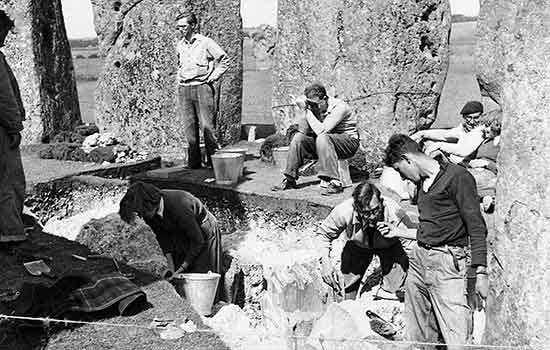

Research on Stonehenge

Our understanding of Stonehenge is constantly changing as excavations and modern scientific techniques yield more information. Read a summary of both past and recent research.

-

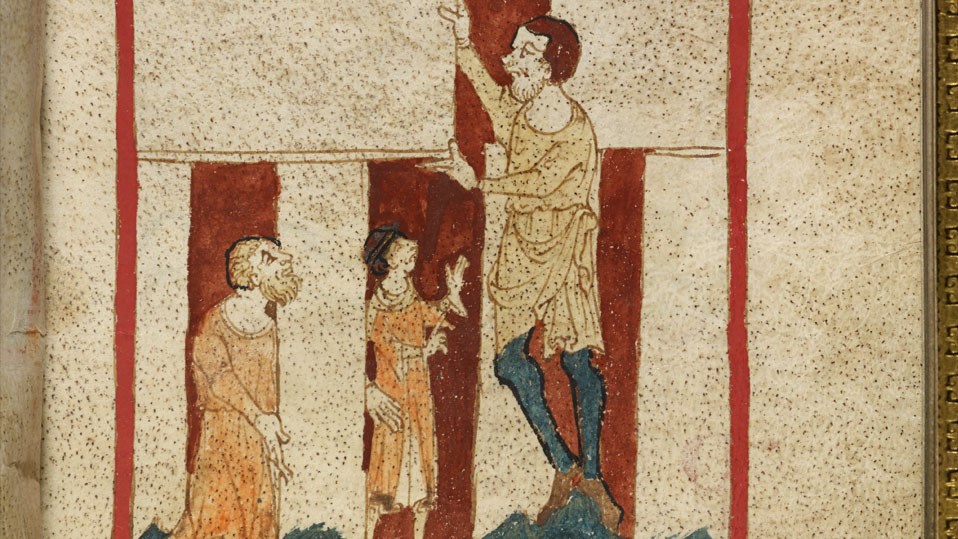

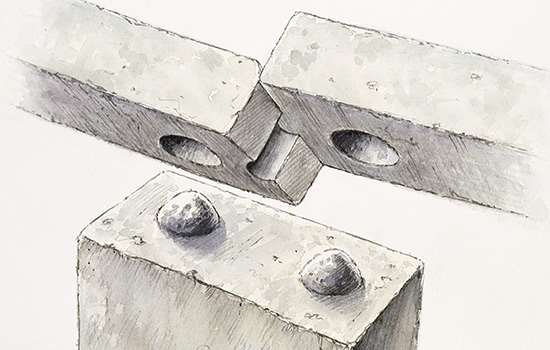

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Why Does Stonehenge Matter?

Stonehenge is a unique prehistoric monument, lying at the centre of an outstandingly rich archaeological landscape. It is an extraordinary source for the study of prehistory.

-

Stonehenge Collection Highlights

Hundreds of prehistoric objects from the Stonehenge World Heritage Site are on display at the visitor centre. You can explore ten of them here in detail.

-

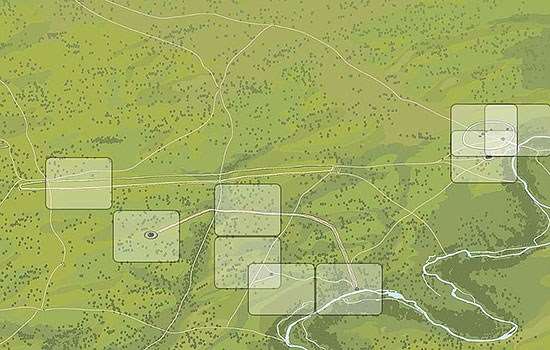

Explore the Stonehenge Landscape

Use these interactive images to discover what the landscape around Stonehenge has looked like from before the monument was built to the present day.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

-

England’s prehistoric monuments

England’s prehistoric monuments span almost four millennia. Discover what they were used for, how and when they were built, and where to find them.