A Military Base

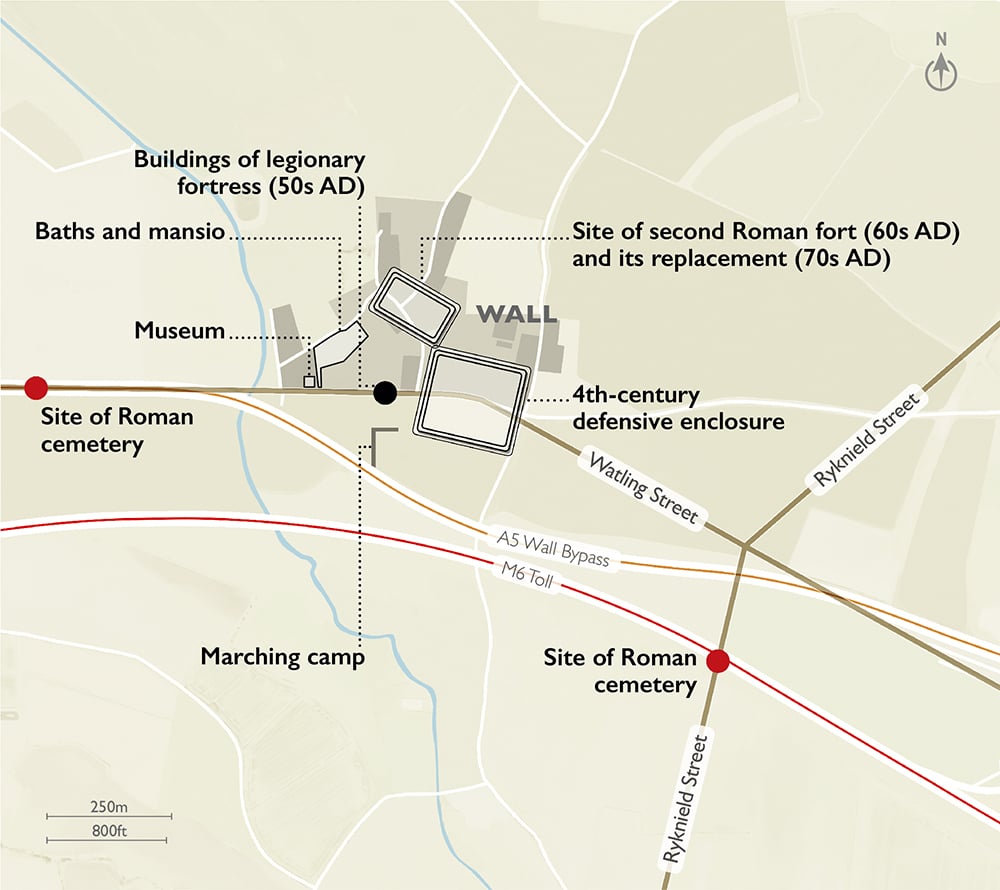

After their invasion of Britain in AD 43, the Roman army advanced north-west from ports in Kent and established marching camps along the way. There were at least two of these at Wall, situated on high ground to the east of the village, overlooking the line of Watling Street and the wider landscape. Watling Street, which runs from Richborough in Kent to north Wales, was the first major Roman road to be developed after the conquest. By the early 50s AD it linked the important towns of London, Wroxeter and Chester. The road provided quick and convenient access to the hot spots that the Roman army would turn its attention to as the conquest progressed.

A fortress was constructed at Wall in the early 50s AD across the line of Watling Street, on flatter ground to the west of the earlier marching camps. This was needed to accommodate part of the XIV Legion. About a decade later, the legion moved on from Wall to Wroxeter and the fort was flattened. Ryknield Street, the major north–south road which crosses Watling Street just east of Wall, was established at roughly the same time. The names of both these roads are Saxon in origin; their Roman names are unknown.

A second fort was constructed at Wall in response to the Boudiccan rebellion in the south-east (AD 60–61). This was on a new site, north of Watling Street, suggesting that the flattened site of the first fort was by then occupied by civilian buildings. Once the rebellion had been suppressed this fort was also levelled. A further fort was built in the same position, and subsequently demolished. This final fort was probably associated with the Roman army’s campaign against the Brigantes in the north, in the 70s AD.

Wall was well placed within the wider travel and communications network. It also lay at the boundary between two tribal areas, the Cornovii to the west and the Corieltauvi in the east. This position on the border between the two territories allowed the Roman army to maintain surveillance on both tribes, while also giving them two hinterlands from which to forcibly extract resources.

A Civilian Town

By around AD 80, Wall (Letocetum) had become an important place by the addition of a mansio, or official guesthouse. Establishments such as this existed to facilitate travel for officials of the Roman empire. They were spaced so that a day’s ride would take a traveller to the next one, where a meal, a bed for the night and a change of horse could be had, though probably not for the general public.

A bath house was added soon after, providing the full suite of services required for those travelling on Rome’s business. The flattened sites of the former forts were reused for civilian and industrial buildings as the town expanded.

Later and Post-Roman Period

Official travel was much reduced in the 3rd century, due to political instability on the Continent, and the mansio was demolished around AD 250. The bath house, which had been enlarged a number of times, survived much longer, until around AD 300. In the 4th century a square defensive enclosure was built across the line of Watling Street, blocking the road, possibly in order to extract tolls from travellers. This smaller but well-defended settlement is likely to have retained key functions such as holding a market and the collection of taxes, but by the end of the 4th century there are clear signs that the settlement at Wall was much reduced in size.

After the end of Roman rule, the 4th-century defensive enclosure may have carried on being used. A poem of the 7th century describes a place thought to be Wall as the subject of cattle raiding by the Welsh. Further evidence of post-Roman activity in the area comes from the unparalleled 7th-century Staffordshire Hoard – the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon treasures ever found. This was discovered a few miles west of Wall on a hilltop overlooking Watling Street. By this date the town of Lichfield to the east of Wall was the centre of power in the region, under the kings of Mercia, but Watling Street remained in use as the principal thoroughfare in the region.

Archaeology at Wall

The archaeological remains of the Roman site extend over a large area and have been routinely encountered by local people working the land. Many excavations have taken place, both on the site of the baths and mansio and on sites of the wider settlement – the forts, domestic buildings and industrial sites, as well as cemeteries.

Today, Wall Roman Site is made up of the excavated remains of the bath house and mansio. The earliest documented excavations of these buildings took place in 1912–14 when local antiquarians investigated the site in the hope of opening it as a visitor attraction.

Unfortunately, the exposed hypocaust of the bath house deteriorated rapidly after 1914 and the underfloor hypocaust was reburied until the mid 20th century, when the bath house and mansio complex were placed in the care of the state. At this time, the archaeologist Graham Webster was brought in to undertake a series of small excavations to clarify the construction history of the bath house, before the consolidation and display of the complex.

Between the 1960s and the 1980s, investigation of the many archaeological sites in and around Wall intensified. There was further excavation of the English Heritage site as well as the forts, farmsteads and industrial sites on its periphery.

An Extraordinary Discovery

During the 1912–14 excavations, nine building stones were found. They were carved with pre-Roman cult images including depictions of horned warriors, Celtic heads and local gods. They had been reused in the construction of the final phase of the mansio, dating to the 170s AD. Some had been laid with their potent images facing downwards or into the core of the wall, and the intent may have been to contain their power and possibly redeploy it for the protection of the new structure.

These carved stones have been interpreted as having come from a Celtic shrine built at Wall in the later 1st century AD, and demolished in the mid 2nd century. The majority of the stones are held by Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, but one stone, depicting a pair of horned warriors facing each other with a shield to their right, is on display in the museum at Wall. This exceptional group of carved stones has much to tell us about pre-Roman belief systems in the wider region.

The Museum and Collections

During the 1912–14 excavations a temporary museum was established on the site. Soon after, that display was made permanent when the finds were moved into a small 19th-century agricultural building nearby, which is still the site museum today.

The current display is predominantly what was on display by the 1930s – mainly objects from the baths and mansio complex and the cemetery west of Wall that was investigated in the 1920s. In addition to the collections on display at the site, English Heritage holds a large and important reserve collection for a small number of the excavations that took place at Wall in the later 20th century.

On display in the site museum are many items of jewellery and ceramics. Highlights of the exhibition include part of a Roman milestone, a lead figurine depicting an African warrior, the carved stone with Celtic horned heads described above, painted wall plaster from the baths and a large group of querns (stone tools used for grinding grain).

By Cameron Moffett

Further Reading

B Burnham and J Wacher, The Small Towns of Roman Britain (Berkeley, CA, 1990)

P Ellis, Wall Roman Site, Staffordshire (London, 1999)

J Gould, ‘The Watling Street “burgi”’, Britannia, 30 (1999), 185–98

J Gould, ‘Letocetum: an early vexillation fortress?’, Britannia, 28 (1997), 350–52

A Ross, ‘A pagan Celtic shrine’, Transactions of the South Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society, 21 (1980), 3–11

AA Round, ‘The bath-house at Wall, Staffordshire: excavations in 1971’ (Wall Excavation Report no. 10), Transactions of the South Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society, 15 (1974), 13–28

AA Round, ‘The mansio: an interim note’ (Wall Excavation Report no. 11), Transactions of the South Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society, 21 (1980)

AA Round, ‘Excavations on the mansio site at Wall (Staffordshire), 1972–78’ (Wall Excavation Report no. 14), Transactions of the South Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society, 32 (1992), 1–78

G Webster, ‘The Roman military advance under Ostorius Scapula’, Archaeological Journal, 49 (1958), 98

G Webster, ‘The bath-house at Wall, Staffordshire; excavations in 1956’, Transactions of the Birmingham and Warwickshire Archaeological Society, 54 (1958), 12–25

Find out more

-

Visit Wall Roman Site

Wall was an important staging post on Watling Street, the Roman military road to North Wales. It provided overnight accommodation for travelling Roman officials and imperial messengers.

-

Lead Figurine of an African Warrior

Find out how recent research into a Roman figurine of an African found at Wall Roman Site in Staffordshire has resulted in a reinterpretation of its identity.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

Explore Roman Britain

Learn more about Roman daily life, politics, religion, art and commerce from our articles about Roman Britain.