Building the Wall

Three Roman legions, each consisting of some 5,000 soldiers, undertook the building work on Hadrian’s Wall, beginning in AD 122. These legions – the 20th Valeria Victrix, based at Chester, the 6th Victrix, based at York, and the 2nd Augusta, based at Caerleon – provided working parties, rotated periodically, leaving others to fulfil military needs in their bases and elsewhere in Britain.

Each legion was made up of smaller units called cohorts, which were subdivided into centuries of around 80 soldiers, each commanded by a centurion. From finds of inscribed ‘centurial’ stones along the Wall, we know that centuries worked as individual teams building specific sections of Wall. Nine such stones have been found in the Walltown section, recording several different centurions and their cohorts.

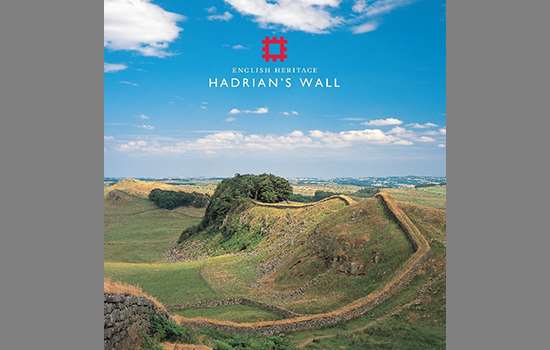

The Wall on Walltown Crags

At Walltown Crags a conserved section of Hadrian’s Wall runs along the edge of the uplifted rocky outcrop of hard dolerite known as the Great Whin Sill, which has created cliffs and steep slopes to the north.

The Wall survives exceptionally well here for almost 400 metres, standing up to 2.2 metres high and averaging 2.18 metres wide, forming one of the best sections along its entire length. Its course undulates to negotiate the frequent nicks or troughs in the surface of the crags.

At both ends, this length of Wall is truncated by the Greenhead Quarry, which gouged out huge sections of rock and destroyed large sections of the Wall in relatively modern times. The quarry was closed in 1976.

The turrets of Hadrian’s Wall

The original design for Hadrian’s Wall comprised a continuous high wall and a V-shaped ditch, stretching 80 Roman miles (117.5km) from Wallsend on the river Tyne in the east to Burgh-by-Sands on the Solway Firth in the west. The builders incorporated about 160 turrets along the Wall, providing vantage points to monitor movements of people, especially to the north.

Pairs of turrets were positioned equidistantly between larger fortlets, known as milecastles, where small garrisons of between 8 and 30 soldiers guarded gates that allowed access through the Wall. During construction of the frontier works, the Roman authorities decided to add large forts, such as Chesters, Housesteads and Birdoswald, to the line of the Wall to house larger forces of about 500 or 1,000 men in each.

The turrets may not all have been permanently occupied, and several were abandoned by the early 3rd century. However, discarded domestic items such as cooking and storage vessels and gaming counters have been found at many of them, showing that turrets provided shelter where small groups of soldiers could cook, sleep and relax during periods of watch and patrol.

Using a system introduced in 1930, turrets are numbered from east to west and given letters as pairs (e.g. 45a and 45b), taking the number of the nearest milecastle to their east.

Walltown Turret (45a)

Turret 45a is unusual in comparison with most others on Hadrian’s Wall. Like other turrets, it has a typical rectangular interior ground plan, about 4.1 by 3.9 metres, walls up to 0.95 metre wide and traces of a doorway towards the east end of the south-east wall. However, the Wall meets the turret walls at distinct angles, whereas turrets are usually perpendicular to it and partially incorporated into the Wall thickness. Most significantly, the joints where the Wall and turret meet are vertical and straight, implying that the turret existed before the Wall was built up to it.

How much time elapsed between the building of the turret and the Wall is unknown. It is possible either that turret 45a is an early design, or that it was a freestanding watch or signal tower built during initial works on Hadrian’s frontier.

Another suggestion is that it was a lookout and signal tower forming part of a frontier a few miles to the south, established over 30 years earlier. This ran along the line of an east–west road, the Stanegate, that crossed the country from the river Tyne to the Solway. Several signal towers were established on high ground north of the Stanegate, keeping watch there, including one with remains 7 miles to the west of turret 45a, at Pike Hill. It was later incorporated into Hadrian’s Wall. However, the absence of Hadrianic finds at turret 45a does not support its construction as part of the Stanegate frontier, even though it is earlier than Hadrian’s Wall itself.

The Military Way, a Roman service road running alongside Hadrian’s Wall, passed close by Walltown Turret and can be detected as a faint terrace in the hill slope, a few metres to the south and more or less parallel to the Wall.

A reconstruction showing Walltown Turret as it may have looked around AD 170

© Historic England/English Heritage Trust (illustration by Peter Lorimer)

Excavations at the turret

Discovered in 1883, the turret was partially exposed three years later and fully excavated in 1913. It was re-excavated in 1959 during the conservation of Hadrian’s Wall on Walltown Crags (see below).

Little was recorded from the earlier investigations, and the most recent excavation revealed that the occupation levels had been largely removed during the previous digs, leaving hardly any undisturbed Roman deposits. The Roman pottery sherds found in disturbed contexts suggested a Hadrianic date for construction of the turret, as there were no finds of an earlier date.

Similarly, the absence of later finds suggested that Roman use of the turret ceased around the end of the 2nd century AD.

Saving Hadrian’s Wall

Public pressure to preserve sections of Hadrian’s Wall, including some parts threatened by active stone quarrying, gained momentum in the 20th century and especially in the 1930s. At Walltown Crags, with quarrying encroaching from east and west, destruction was averted in 1943 when an area was defined for preservation. It was finally secured by the government paying compensation to the quarry owners.

The Ministry of Works began consolidation on Walltown Crags in 1959 and continued into the mid-1960s, supervised by Mr Charles Anderson. When the workmen removed topsoil and collapsed walling, Hadrian’s Wall was revealed to be in good condition here, with only the top two courses of stone requiring removal and re-setting. For the rest, raking and washing out old mortar and soil in the joints between stones was followed by extensive repointing.

In the course of this work, nine centurial stones were discovered, as were several chamfered stones (cut with sloping edges). These had probably formed a string course at the junction of the Wall top and its parapet.

The results of Mr Anderson’s painstaking work remain today.

By Paul Pattison

The Wall nearby

From Walltown Crags you can walk 3 miles eastwards along the Wall to milecastle 39 at Cawfields, or 3¼ miles westwards to the Wall and bridge at Willowford. From there another ½ mile walk takes you to Birdoswald Roman Fort.

-

Visit Birdoswald

Birdoswald has the best-preserved defences of any Wall fort, while just outside it is the longest continuous stretch of Hadrian’s Wall visible today.

-

Visit Cawfields Roman Wall

This fine stretch of Hadrian’s Wall on a steep slope includes turrets and an impressive milecastle, which was probably built by the Second Legion Augusta.

-

Visit Willowford Wall, Bridge and Turrets

A fine 914-metre stretch of Wall, linked by a bridge to Birdoswald Roman Fort and including two turrets and impressive bridge remains beside the river Irthing.

More about Hadrian’s Wall

-

Hadrian’s Wall: History and Stories

Discover the history and stories associated with Hadrian’s Wall, the north-western frontier of the Roman Empire.

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.

-

Buy the guidebook to Hadrian’s Wall

The English Heritage guidebook to the Wall provides maps, plans and tours of all the key sites, as well as a history of the Wall and its forts.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.