Beware Women in the Garden

Superstitions surrounding the danger of women in the garden, especially menstruating women, can be traced back to Roman writers. Some superstitions may even have been older – the association with Eve, apples and the Garden of Eden leading to wariness when it came to women in orchards.

In the 16th century gardening manuals repeated these superstitions. William Turner, quoting Pliny wrote:

And let weomen nether touche the yonge gourds nor loke upon them, for the only touchinge and sighte of weomen kille the yonge gourds.

Similarly, Thomas Hyll, in The Gardener’s Labyrinth (1577), shares the risk relating to cucumbers:

that no woman, at that instant, having the reds or monthly course, approcheth nighe to the fruites, especially handeleth them, for through the handling, at the same tyme they feeble and wyther.

None of these superstitions, however, seem to have prevented women being used as cheap labour in gardens throughout history.

Back-breaking work

Women working in a garden were often tasked with weeding and sometimes referred to simply as ‘weeding women’ or ‘weeders’. They were also given other monotonous tasks such as pest control, looking for insects and caterpillars, and gathering fruit, or they could be employed as ‘bothy women’ – cooking and cleaning for the gardeners who lived on site in a garden building known as a bothy.

Garden work was irregular and women were employed seasonally and only when needed, usually earning half the pay of a male labourer and often less. They were sometimes even paid less than a garden boy for similar work.

This work, however, was one of the few ways ‘respectable’ working-class women could earn money, and could provide a lifeline for unmarried women and widows in the countryside where there might be a lack of other employment. Sometimes they were the wives of gardeners or estate workers, adding a small supplement to the household income.

Where are the Weeders?

Trying to trace the history of these women is almost as painstaking as the work they were employed to do. It involves trawling through estate accounts for very brief mentions. The reason behind this lack of recording is perhaps unsurprising; it is likely such women were so commonplace and undervalued that it was unnecessary to give any details on them or their role.

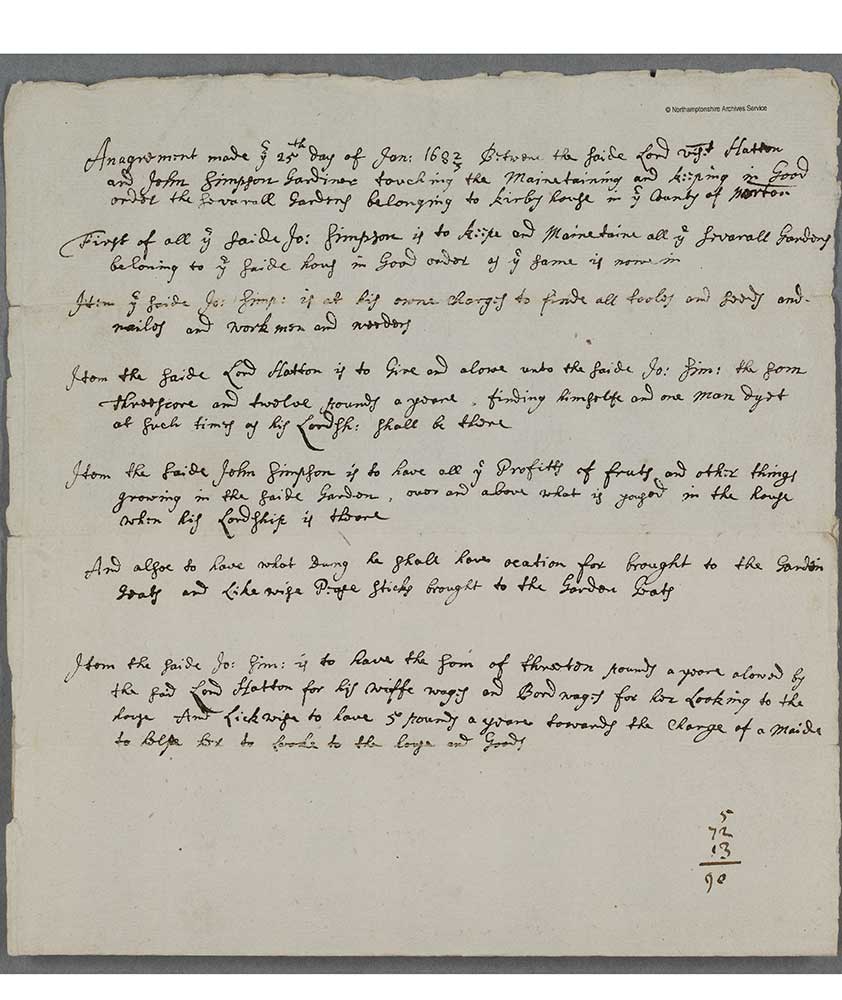

There are some clues as to the existence of women weeders in a contract drawn up at Kirby Hall, Northamptonshire, between Lord Hatton, the owner, and his new head gardener John Simpson. The contract, dated 25 January 1682, outlines that Simpson will be paid £72 a year from which he must pay all the labourers in the garden including ‘workmen and weeders’. While it is not certain that these ‘weeders’ were women, the fact that they are set alongside the ‘workmen’ perhaps implies that this is a different form of labour, probably women.

A few decades later at Wrest Park, Bedfordshire, the records are more detailed. In an ‘account of the expenses in keeping [W]Rest gardens weekly’ from December 1716 to December 1717 we learn that women were employed to work in the gardens only from April to the end of October. Most were employed in April and May when there were 7 women labourers, 4 garden boys and up to 30 men working in the garden.

Some 19th-century clues

In the 19th century more traces come to light as records survive that provide further detail on those who worked in the households and gardens of large estates.

At Brodsworth Hall, South Yorkshire, in 1829 the under gardener was paid £36 8s per year, and in comparison the wage for ‘two women or boys to work in the gardens’ was £20 18s each. In this case we can see the stark contrast in wages between the skilled garden labourer and the woman labourer or boy.

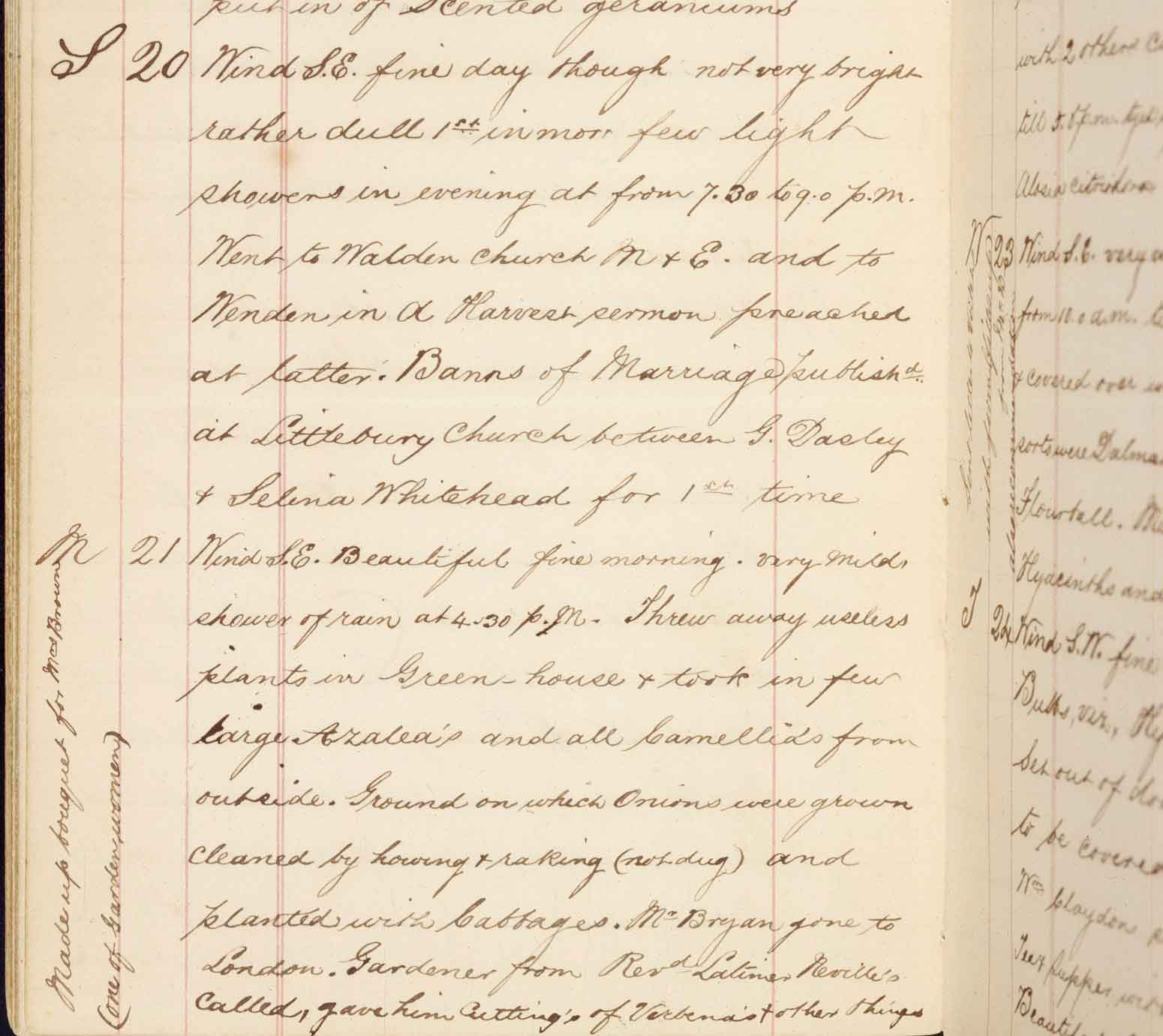

The women who worked in the garden at Audley End House in Essex in the late 19th century are individually named and therefore more depth can be added to their stories. A rare surviving diary from a gardener at Audley End in 1874 records how the ‘Garden woman forgot to bring clean linen’. In September he then ‘made up bouquet for Mrs Brown (one of Garden women)’ from some left over plants. If she was the one who had forgotten the linen, she was clearly forgiven!

Changing times at Eltham Palace

Careers as professional gardeners would soon become open to women; Kew Gardens started admitting women trainees in 1901. However, it wasn’t until the more traditional hierarches were overturned during the Second World War, when many of the able-bodied men had gone off to fight, that Christine Falwasser found herself promoted to deputy head gardener at Eltham Palace in south-east London.

In England the early 20th century saw the start of a shift for middle-class women to see horticulture as a career, as respectable as nursing or teaching. As a Cambridge history graduate Falwasser was fortunate to have a very different route into the garden compared to the working-class women weeders of previous centuries.

However, despite her more privileged upbringing, even Falwasser was aware of the unsung role of women in gardens during her time and in the past. In 1957, after she had left Eltham Palace, she wrote a piece for the Gardeners’ Chronicle about Majorca in which she reflected on the role of women as weeders:

Weeding? Women’s work naturally – even in sunny Majorca. When women are scarce, the weeds spread, even in the famous Moorish gardens of the past.

Later in the article she mentions it again, highlighting (perhaps with some sarcasm) that ‘as in most other parts of the world, weeding was women’s work’.

Written by Emily Parker

Further Reading

T Way, Virgins, Weeders and Queens (Stroud, 2006)

C Horwood, Gardening Women (Bath, 2011)

S Campbell, A History of Kitchen Gardening (London, 2016)

R Floud, An Economic History of the English Garden (London, 2019)

Top image: From The Bystander, July 1906. (courtesy of the Garden Museum)

Explore more

-

Women in History

Read more about the women that shaped the course of English history, from great queens, writers and scientists, to those that broke the mould or remain largely unnamed.

-

Visit our Gardens

Find beautiful gardens to visit and learn more about the history of gardens through the ages.

-

Gardens through time

Explore how garden and landscape design has evolved in England, from the Romans to the 20th century.

-

Caring for our Gardens

Learn more about the important work that our gardens team are doing to care for and protect our historic gardens and landscapes.