The Anglo-Saxon monastery

Merewalh, ‘subking’ of Magonsaete, a subkingdom of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, founded the first monastery at Wenlock between 670 and 680.

Called Wimnicas, it was a ‘dual house’ – a community of both monks and nuns. Double monasteries of this type originated in France, and were not uncommon between the 7th and 9th centuries. At their head was an abbess, almost always of royal birth. Wenlock’s second abbess was Milburga, the daughter of Merewalh and his queen Domne Eafe, who was also an important founder of monasteries.

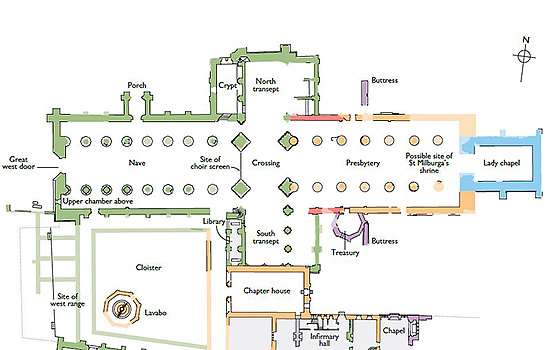

The monks and nuns at Wenlock and other double monasteries had separate buildings, worshipping in their own churches. The monks’ church was located under the crossing of the later medieval monastery and the parish church stands on the site of the nuns’ church. It was here that Milburga was buried after her death in 715.

Little else is known about the history of the Anglo-Saxon monastery. It is likely that it remained a dual house until the early 10th century: a charter of 901 says that Wenlock was a minister with a priest in charge. Its four female witnesses are likely to have been nuns. However, at some point in the 10th century, nuns ceased to be part of the community. Their church fell into ruins and the burial place of St Milburga was forgotten.

Despite this, the male community continued to thrive. Earl Leofric of Mercia (d.1057) presented their church with ‘precious ornaments’.

The post-Conquest monastery

William the Conqueror’s victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 had important consequences for the English church, an upheaval that extended to Wenlock. Between 1080 and 1082, Roger Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury and a rich and powerful Norman lord, refounded Wenlock as a priory for Cluniac monks.

The Cluniacs were one of the most important monastic reform movements of the Middle Ages. At the head of the order was Cluny Abbey in France, which founded a network of dependent daughter houses across Europe.

Wenlock was founded by monks from La Charité-sur-Loire in central France. Bonds between the monasteries endured until the end of the 15th century.

The monks set about building a stone monastery. They replaced the Anglo-Saxon church with a much larger structure, the plan and architecture of which owed much to Cluniac monasteries in France. Services were being held there by about 1100.

The priory prospers

It was around 1100 that relics of St Milburga were rediscovered in the ruins of the former nuns’ church. They were moved, or translated, to the monks’ church. A life of Milburga was written by Goscelin de Saint-Bertin, a Benedictine monk famous for his hagiographies (idealised lives) of saints. Miraculous cures were attributed to St Milburga, including the healing of lepers and the restoration of sight to the blind.

The monastery was dedicated to St Michael and St Milburga and two feast or holy days were observed in her honour: 25 June and 23 February, the latter a ‘translation’ feast commemorating the moving of her relics to the priory church. Her relics were carried in procession outside the priory at Whitsuntide (the seventh week after Easter).

Building works continued at the monastery. A new east end of the church was completed between 1180 and 1200, as was the magnificently sculpted ‘lavabo’ where the monks washed ceremonially before dining. Further gifts of land enhanced the priory’s wealth, and in 1167 it founded its own dependent priory at Church Preen, Shropshire.

Prior Humbert (r. 1221–61) served as an envoy to the Welsh on behalf of King Henry III, who stayed at Wenlock on several occasions in the 1230s. The king also favoured the priory with his patronage, making numerous gifts of timber from the royal forests for building work. This included a grant of oaks in 1233 for the ‘horologium’, probably a clock tower.

In 1262 the abbot of Cluny conducted a visitation, or inspection, of the priory. He reported that there were 44 monks, a very healthily sized community for this time, and that the spiritual state of the monastery was excellent.

Wenlock was a wealthy monastery. It derived an income not only from its large landed estates, many of them held from Anglo-Saxon times, but also from the ‘new town’ it developed at Madeley, 8 miles away. A weekly market and annual fair were held at the town. It was also a base for mining operations, including coal and ironstone. A coalmine at Madeley is mentioned in 1390 and in 1397 the priory employed a James Mynor of Derbyshire to mine copper and silver on its estates.

Nevertheless, the monks were living beyond their means. In 1262 the monastery was over £1,000 in debt, probably due to the extensive building works taking place around this time. From the early 14th century it was also burdened with the expense of providing food, lodging and fuel to former royal servants, sent to the monastery to live out their retirement as corrodians, or pensioners.

The severing of French ties

Wenlock’s close relationship with Cluniac monasteries in France meant that it was classified as an ‘alien priory’. The situation became especially severe after 1337 and the outbreak of what we now call the Hundred Years War. King Edward III ordered the seizure of all alien priories, and Wenlock only escaped after it agreed to pay an annual fine of £170 to the Crown. This was more than half the priory’s income, and although the amount was subsequently reduced to £133 it was still more than the monastery could afford.

The only way of escaping this crippling financial burden was for Wenlock to denounce its centuries’ long ties with La Charité and for the prior and monks to swear they were English, a process known as denization. A substantial fee of £400 was also demanded when the monks took the required oaths in February 1395.

However, La Charité continued to claim jurisdiction over Wenlock, and it was only in 1494 that Prior Richard Synger obtained papal approval for severing all the priory’s historic connections with its French mother house.

Above: A fly-through reconstruction of the chapter house as it may have looked in about 1400. © Historic England/English Heritage Trust (illustration and animation by Martin Moss)

The priory’s final years

Richard Synger and his successor, Rowland Gosnell (r.1521–7), were responsible for the last major building works at Wenlock. Synger repaired the vault above the east end of the church, while Gosnell reglazed the nave, and both oversaw building works to other monastic buildings.

Gosnell was clearly a learned man, composing a chronicle of the priors of Wenlock and ordering the writing of a new set of miracles of St Milburga. Two of six surviving books from Wenlock have his ownership inscription. He also secured permission from the pope to wear the mitre and other ornaments normally reserved for bishops, a much sought-after privilege at this time.

Gosnell also tried to improve the quality of monastic observance at Wenlock, and forbade the monks to leave the monastery without permission, to hunt and to play dice. However, a faction of monks would not accept his authority. By 1527 he had been forced to resign, and was succeeded as prior by John Bayly.

Chapter house reconstruction by Martin Moss

Move the sliding bar to compare a reconstruction of Wenlock Priory as it may have looked at the time of its dissolution in 1540 with a present-day view. (Illustration by Peter Urmston © Historic England)

Dissolution

The monastery was soon caught up in the religious changes instigated by Henry VIII. In 1535 its income was assessed at over £400, thus sparing it inclusion in the round of monastic closures of ‘lesser’ monasteries the following year. However, almost 900 years of unbroken monastic life at Wenlock finally came to an end on 26 January 1540 when Prior Bayly and his 12 monks gathered in the chapter house to surrender their monastery to the king’s commissioners.

Bayly received a generous pension of £80 a year, the monks between £5 and £6. One of them, Thomas Butler, became the parish priest at Much Wenlock and kept a book recording the subsequent careers and deaths of his former brethren.

The monastery was stripped of its valuables, and the lead was removed from the roofs of most of the buildings, including the magnificent church, which fell into ruins. However, the former prior’s lodging and infirmary were preserved as a high-status private dwelling for the new owners of the site.

Decay and rediscovery

The house gradually fell in status, and by the 17th century it was being used as a farmhouse, the ruinous buildings around the cloister put to agricultural uses.

Starting in the 19th century, the site began to attract the interest of artists and antiquarians. It was bought in 1856 by James Milnes Gaskell, who turned the former prior’s lodging into a comfortable gentleman’s house. The restoration of the house and the laying out of formal gardens within the monastic ruins were continued by his son, Charles, and wife, Lady Catherine, a notable socialite and author. Their guests at Wenlock included Henry James and Thomas Hardy, both among the greats of English literature.

The first modern excavations at the site were conducted in 1901 by David Cranage, curate of the parish church, who found evidence of an Anglo-Saxon church beneath the crossing of the later medieval church. In 1962 the priory ruins were transferred to the care of the Ministry of Works, which led to more excavations.

Further digs were conducted in the early 1980s, adding to understanding of the development of the site and the lives of the nuns and monks who lived and prayed there between the 7th and 16th centuries. English Heritage now cares for the ruins.

Further reading

MJ Angold et al, ‘The abbey, later priory, of Wenlock’, Victoria County History of Shropshire, Volume 2, ed AT Gaydon and RB Pugh (London, 1973), 38–47 (accessed 6 Nov 2020)

V Bellamy, A History of Much Wenlock (Much Wenlock, 2018)

M Biddle and B Kyølbe-Biddle, ‘The churches of Much Wenlock’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 141 (1988), 178–83 (subscription required; accessed 6 Nov 2020)

D Cranage, ‘The monastery of St Milburge at Much Wenlock, Shropshire’, Archaeologia, 72 (1922), 105–32 (subscription required; accessed 6 Nov 2020)

C Gamble, Wenlock Abbey 1857–1919: A Shropshire Country House and the Milnes Gaskell Family (Much Wenlock, 2015)

R Graham, ‘The history of the alien priory at Wenlock’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 3rd series, 4 (1939), 117–40 (subscription required; accessed 6 Nov 2020)

D Jackson and E Fletcher, ‘The pre-Conquest churches at Much Wenlock’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 3rd series, 28 (1965), 16–38 (subscription required; accessed 6 Nov 2020)

J McNeill, Wenlock Priory (English Heritage guidebook, London, 2019)

WF Mumford, Wenlock in the Middle Ages (Shrewsbury, 1977)

H Woods, ‘Excavations at Wenlock Priory, 1981–6’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 140 (1987), 36–75 (subscription required; accessed 6 Nov 2020)

S Yarrow, ‘The invention of St Mildburg of Wenlock: community and cult in an Anglo-Norman Shropshire town’, Midland History, 38:1 (2013), 1–15 (subscription required; accessed 6 Nov 2020)

Find out more

-

Visit Wenlock Priory

The impressive remains of the priory stand in a tranquil and picturesque setting on the fringe of beautiful Much Wenlock.

-

St Milburga

Read more about St Milburga, Anglo-Saxon princess, abbess and miracle worker, who ruled over a community of both monks and nuns.

-

WHAT BECAME OF THE MONKS AND NUNS AT THE DISSOLUTION?

Discover what happened to the many thousands of monks and nuns whose lives were changed forever when, on the orders of Henry VIII, every abbey and priory in England was closed.

-

Buy the guidebook

This fully illustrated guidebook contains a comprehensive history of the priory as well as a complete tour of the impressive remains.

-

Download a plan

Download this detailed ground plan of the priory to see how its buildings developed over time.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.