Tiny cakes and sandwiches, freshly baked scones, buttered toast and a pot of tea – what could be more English? But how, when and why did the ritual of afternoon tea evolve – and how can we recreate it today? Food blogger Sam Bilton explores the institution that is afternoon tea.

Time for tea

“There are few hours in life more agreeable than the hour dedicated to the ceremony known as afternoon tea.”

Henry James, The Portrait Of A Lady, (1880)

Tea became the nation’s beverage during Queen Victoria’s reign. Lower taxes on tea and the expansion of plantations in India (the plant had originated in China) meant there was more affordable tea than ever before, making it accessible to more levels of society.The working classes bought hot sweet tea from street vendors and tea drinking crops up in many of Charles Dickens’ stories. In Pickwick Papers Mrs Gamp is thrilled to have been asked to prepare the tea as a side table for a party:

“The privileges of the side table included the small prerogative of sitting next to the toast, and taking two cups of tea to the other peoples one.”

The Queen herself was very fond of tea and mentions it 7,000 times in her journals.

A Little Something To Tide You Over

The custom of afternoon tea came about as a necessity to fill a hunger gap. In previous centuries dinner had been served early to mid afternoon but towards the end of the Georgian era it had slipped back to 5 or 6 o’clock. By Victoria’s reign it was not uncommon for dinner to be served at 7pm or even later on important occasions.

Some sustenance was needed to bridge the gap between breakfast and dinner

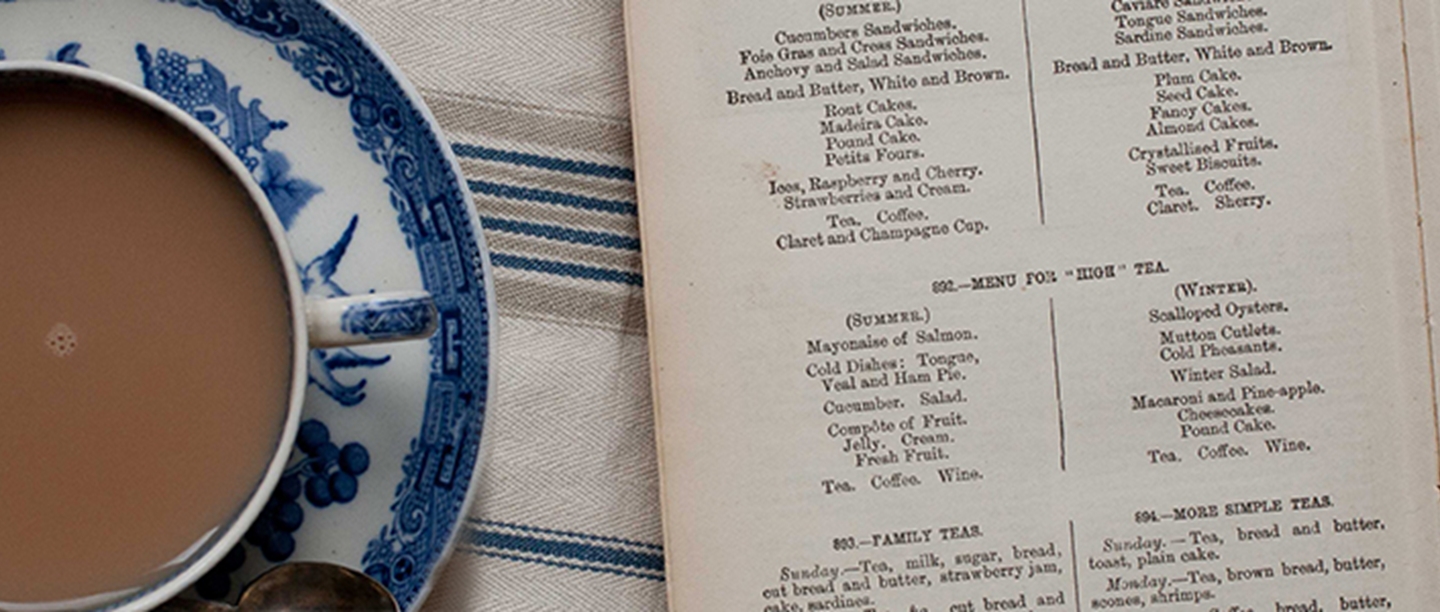

Some sustenance was needed to bridge the gap between breakfast and dinner and so the habit of taking tea in the afternoon was born, often served around 5pm. According to Mrs Beeton afternoon tea “seems to the feminine mind almost a necessity where dinner is late.”

Tea alone would not have satisfied this peckishness so it was customary to serve something along side the drink. Mrs Beeton notes that wealthier families could afford “a great variety of dainty eatables and drinkables” whereas the less fashionable (i.e. poorer) folk may just serve bread or toast and butter.

The Perfect Cuppa

Although in other cultures there are distinct rituals associated with tea making in Victorian England there appears to be no real art behind the process.

Most contemporary authors agree the pot should be warmed first. In his 1849 publication Ménagère or The Modern Housewife, Alexis Soyer advocates warming both pot and leaves before adding boiling water by placing the pot in a warm oven; leaving it in front of the fire or placing it over a small spirit lamp. Other authors simply instructed their readers to warm the pot with boiling water prior to making the tea.

Always warm your teapot before making tea.

Two factors which did affect the outcome of the final beverage were the quality and quantity of leaves used. Although the price of tea had come down considerably there was still a market for counterfeit tea leading Mrs Beeton to warn:

“In the purchase of tea, therefore, it is well to see that it possesses an agreeable odour and that the leaves be as a whole as possible.”

At best, adulterated tea would be recycled leaves dried and sold on to vendors by unscrupulous maids. At worst it could be elder, ash or sloe leaves which had been dried and coloured with logwood or verdigris in the case of green tea. The former ingredient was known to cause gastroenteritis if consumed in large quantities.

In the 18th century tea had been incredibly expensive and was therefore use sparingly. It was stored in lockable tea caddies which remained under the mistress’s watchful eye. As the price of the leaves reduced, the quantity used increased. A teaspoon of tea leaves per person was the accepted norm, although if providing tea for a large number of guests more than one pot was recommended. The average brewing time was around five minutes.

Milk And Sugar?

The habit of adding sugar to tea had to be a common practice since it had been introduced in the 17th century. This was to counteract its slightly bitter nature. As with tea, the price of sugar would also have come down during Victoria’s reign, and consequently consumption increased.

When tea was first introduced to England it was drunk black. This is possibly because it was used in such small quantities that adding milk would have diluted the delicate flavour. In some quarters it was believed that too much tea could be injurious to health and that adding milk could counter its potential ill effects.

Minding Your Manners

What set afternoon tea in middle and upper-class households apart from the working classes was the etiquette that needed to be observed.

Afternoon tea was seen as a social event. It was an opportunity to assess others – whether that be as an acquaintance or potential marriage material. Woe betide anyone who broke the unspoken rules.

Afternoon tea treats, made by Sam. Delicate cakes showed how refined a hostess was, and were a mark of social status.

Fortunately they were books available to help hostesses and their guests navigate this minefield of manners. Publications like The Ladies Book Of Etiquette And Manual Of Politeness by Florence Hartley (1860) provided advice on everything from how to dress to table etiquette. Blowing on your tea to cool it down or drinking it from a saucer were definite no-no’s!

How to make Victoria Sandwich sponge cakes

The Servants’ Wing at Audley End House in Essex is the perfect place to experience Victorian life. Mrs Crocombe, the Victorian cook, is making a Victoria Sandwiches for Lord and Lady Braybrooke in the kitchens of Audley End.

Follow her authentic Victorian recipe and try making this classic treat at home:

INGREDIENTS:

- 675g Sugar

- 6 Eggs

- 450g Flour

- 2 tsp Orange Flower Water

- 1 tsb Baking Powder

- 90g Almonds

TO MAKE VICTORIA SANDWICHES:

Preheat your oven to 180 degrees. First, whisk your eggs until they are frothy. Add the sugar and mix together gently. Now sift in the flour. Next add your almonds. Add the baking powder and orange flower water and mix well. Line your baking tin with butter and the dust it with sugar. Pour in your mix and bake in the oven for around 25 minutes until the sponge is pale and golden. Once cooled, cut the cake into manageable pieces and spread with jam to serve.

Find more Victorian recipes here on the English Heritage website and watch more from Mrs Crocombe at Audley End on our YouTube channel.