The eagerly awaited second half of Sam Kinchin-Smith’s rundown of some of the most inspiring women from the histories of our places includes a philosopher, a royal mistress and the architect of the modern state of Iraq.

There are five stories here – if you missed part one you can read it here

Anne Clifford, 1589–1676

Hell hath no fury like a daughter denied her inheritance – so the saying doesn’t go. Which might be why Lady Anne Clifford’s father believed, after losing his two sons, that he could keep the family estates in male hands after his death by breaching long-established entail and giving them to his brother – while paying off Anne with £15,000 of hush money. But he was wrong.

Anne would spend the next four decades fighting to recover her lost lands. Supported by her mother – and for a while by her husband, before he lost his appetite for the struggle, exhausted by his wife’s commitment to her cause – she initially sought recourse in the courts. The Earl Marshal’s Court refused her claims in 1606; the Court of Wards agreed that properties in Skipton were rightfully hers; and the Court of Common Pleas tried to palm her off with a half-and-half split with her Uncle Francis. Anne refused all such settlements. James I himself intervened to discourage her, but she continued to pitch for the whole lot, ignoring increasingly generous compensation proposals.

It was only in 1643, when Uncle Francis died, that she recovered her properties. She spent the remainder of her life restoring her neglected castles, including Brough and Brougham – and it was at the latter that she died.

Anne, Countess of Pembroke, by William Larkin. © National Portrait Gallery, London, creative

commons license

Margaret Cavendish, 1623–73

Margaret Cavendish’s story intersects with those of several of the women on this list: she too was wrongly denied estates that were her due (although she gave them up after just the one appeal); her husband’s daughters from his first marriage engaged in acts of Royalist resistance at Welbeck Abbey almost as courageous as Blanche Arundell’s; and said husband, Bolsover Castle’s prince of pleasure William Cavendish, was none other than Bess of Hardwick’s grandson. His unconventional taste in women was no doubt influenced by his indomitable grandma.

For even her greatest fans have generally regarded ‘Mad Madge’ as a bit of a fruitloop. And it’s certainly tempting to focus on eccentricities such as her peculiar outfits and her tendency to swerve between bouts of extreme nervousness (she was regarded as a silent simpleton by Henrietta Maria’s court in exile) and breathtaking intellectual self-confidence: in the epilogue to her proto-science fiction masterpiece, The Blazing World, she writes that ‘concerning the Philosophical-world, I am Empress of it my self’. Actually, though, she had a point.

Probably the most published female author of the 17th century, and one of the most prolific woman philosophers of the early modern period, her published Opinions, Observations and Orations are widely considered to have anticipated some of the central arguments concerning natural and political philosophy, gender studies and religion, espoused by much more famous (male) thinkers from Thomas Hobbes to Baruch Spinoza.

Bolsover Castle, the ‘pleasure palace’ William and Margaret Cavendish enjoyed together

Delarivier Manley, c.1663–1724

Presumably because of her social status, the intellectual establishment of the past 400 years has been a hell of a lot kinder to Mad Madge than another pioneering authoress, Delarivier Manley. Cavendish had to deal with raised eyebrows and sniggers; Manley, meanwhile, has been subjected to some of most vicious abuse ever directed at a female intellectual. No less a figure than Winston Churchill regarded her as a peddler of ‘the lying inventions of a prurient and filthy-minded underworld’, and regretted that she ‘cannot be swept back into the cesspool from which she should never have crawled’.

Her appalling reputation largely stems from her scandalous private life, notable for her apparent sexual autonomy and disregard for the prejudices of her peers, and her savvy and pragmatic approach to literary careerism, prioritising survival over artistic integrity (and becoming one of the first English women to earn a living from writing in the process).

The daughter of the Governor of Landguard Fort, Manley fell madly in love with a young ensign stationed there, before being lured into a bigamous marriage with her father’s nephew. Three years and one son later, she left him and became a companion of an ex-mistress of Charles II who was addicted to gambling, and then embarked on a series of affairs with a married lawyer, her publisher and (possibly) various other patrons and colleagues. In parallel, she became a strikingly effective Tory propagandist, humiliating illustrious Whigs such as Churchill’s ancestor, the Duke of Marlborough, with an allegorical masterpiece titled The New Atlantis, before inheriting the editorship of The Examiner from Jonathan Swift.

Perhaps her greatest achievement was to weaponise her clear-eyed sexual authority, experience and frankness as the engine of much of her writing’s incisive and satirical power, and place her own story at the heart of her magnificently biased critiques of social and political hypocrisy in her autobiographical Adventures of Rivella – rather than simply accept her status as a fallen woman.

Henrietta Howard, c.1689–1767

Manley was sometimes characterised as one third of the so-called ‘fair triumvirate of wit’, alongside Aphra Behn and Eliza Haywood. One of Haywood’s most controversial literary interventions was to savage Henrietta Howard, mistress to the Prince of Wales (the future George II) and friend of Alexander Pope and Swift, who furiously denounced Haywood as a ‘stupid, infamous, scribbling woman’. Interestingly it was Pope and Swift, rather than her philosophical sisters, who recognised Howard for what she really was: a canny and courageous arch-pragmatist, perhaps even more skilled at playing a system with the odds stacked against her than these pioneering women writers.

Henrietta had sailed to Hannover (selling her hair to buy her passage) in order to ingratiate herself with the future first family, driven mainly by her desire to escape an appalling, abusive husband. Thanks to an attractive combination of smarts, low-key charm and a rather un-Georgian willingness to listen (rather than constantly bray and quip) she became a Woman of the Bedchamber to George’s wife Caroline, and eventually the King’s mistress. Theirs was a pretty passionless affair, indulged by Caroline and largely the result of Henrietta’s infinite patience with George’s tedious tales.

He was financially kind to Henrietta, though, and eventually she was wealthy enough to build her own villa, Marble Hill House, and pay off her husband. Marble Hill became her happy place: initially, it was a refuge from the monotony of court, where she hosted a literary salon attended by the greatest minds of the age. Then it became the centre of her splendid second life, which saw the middle-aged Henrietta marrying for love, befriending Horace Walpole and outliving the King by seven years. She who laughs last.

Henrietta Howard, by Charles Jervas

Gertrude Bell, 1868–1926

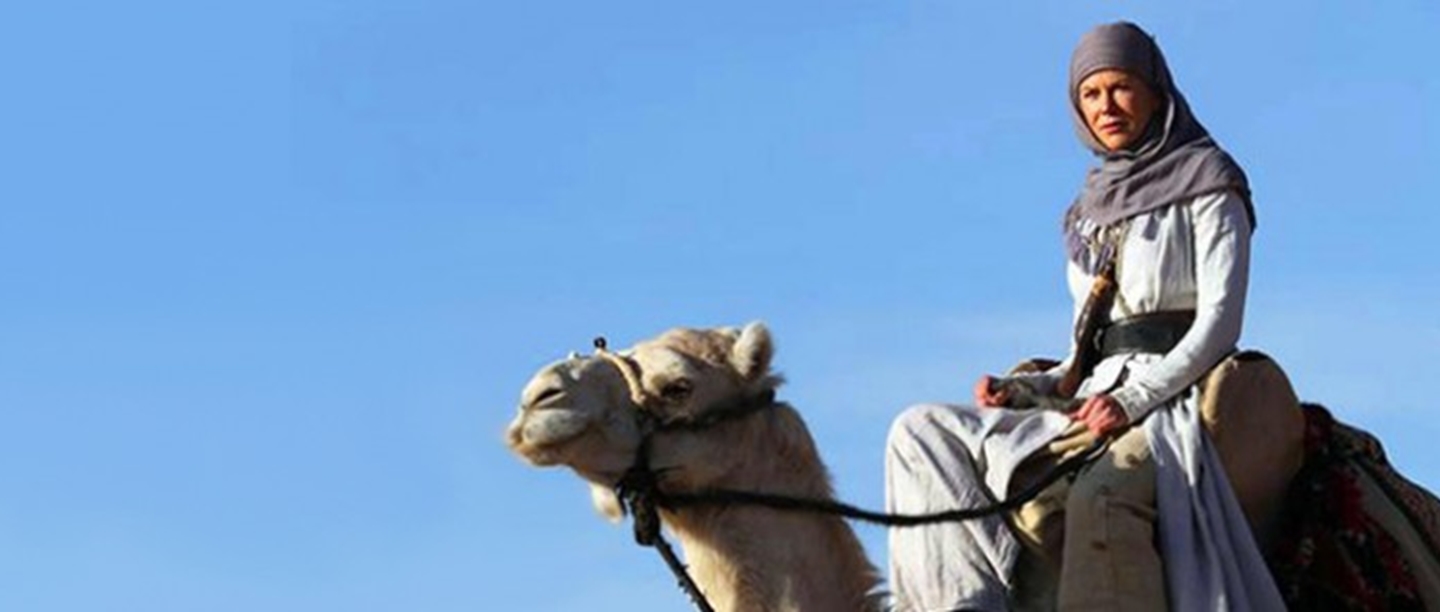

Our rundown ends with a woman who maybe ‘made it happen’ more than anybody else in the list, but will soon lose her claim to being ‘lesser-known’ thanks to two recent films, Queen of the Desert, starring Nicole Kidman (image courtesy of Ascot Elite Entertainment Group) and a documentary, Letters from Baghdad. After a fairly conventional upper class upbringing in County Durham, London, and then at Oxford University – with frequent country house weekends at her grandfather’s house, Mount Grace Priory – Gertrude Bell embarked on the travels that would occupy her extraordinary life.

After long periods in Bucharest and Tehran, two round-the-world trips, and a number of unprecedented mountaineering expeditions, Bell became obsessed with the Middle East. Years of cultural immersion, writing and archaeological study alongside figures including T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia) followed, before she was recruited by British Intelligence during the First World War. Her expertise, and Lawrence’s, exerted a huge influence on British policy in the region, and both were invited to help determine the boundaries of the British mandate and the fates of nascent states such as Iraq in the aftermath of the war.

In addition to being one of the architects of its eventual borders, Bell became a powerful force in Iraqi politics. She could even be described as its kingmaker when her preferred choice, Faisal, was crowned King of Iraq in August 1921. Her focus soon returned to archaeology, however, and she became Honorary Director of Antiquities in Iraq, establishing its National Museum. It opened shortly before her death, in 1926. She has been described as ‘one of the few representatives of His Majesty’s Government remembered by the Arabs with anything resembling affection’.

Mount Grace Priory, where Gertrude Bell spent her weekends

For more on Women in English History

Read part 1 of Sam’s look at women who have ‘got things done’ here

Visit our Women in History hub page

YOU ALSO MIGHT ENJOY:

- Women in 1066: the power behind the throne

- What was the role of women on Hadrian’s Wall?

- 19 inspirational things that women in English history have done

- Why was Queen Elizabeth I so important?