The Road to Evesham

In the 1260s England was a kingdom divided. Henry III and Lord Edward were at war with Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, who was the leader of the baronial reforming group. In 1264 Simon inflicted a major defeat on the royal army at Lewes in Sussex, capturing both the king and Edward. But in May the following year, Edward managed to escape. Joining up with his allies, he began a campaign of harassment against the Earl of Leicester’s forces, which were then west of the river Severn.

In early summer 1265 the Earl of Leicester’s second son, Simon junior, marched with an army from London. In July they were camped, apparently undefended, outside Kenilworth Castle, the Montfortian stronghold. There Simon planned to join his father’s forces, who were being shadowed by Lord Edward’s supporters.

However, Edward was informed of Simon junior’s vulnerable position at Kenilworth and, marching through the night, launched a devastating surprise attack, forcing Simon junior to flee with part of his army. Edward went on to nearby Evesham, using banners captured from the Montfortians as cover. There he defeated the Earl of Leicester in battle, freeing the king and thereby fatally wounding the rebellion.

In 1266, after the famous siege of Kenilworth Castle, Henry III captured this major Montfortian stronghold, although the siege did little to restore peace.

Margoth the spy

In describing how Edward discovered the vulnerability of Simon junior’s army at Kenilworth, Walter of Guisborough – writing about 50 years later – records the following (translated from the Latin, shown below):

Edward the king’s son was informed of this by his spy Margoth, who while being a woman, went in men’s clothes as a man, and by Ralph of Ardern, who despite being on the opposing side, betrayed and deceived his comrades.

Apart from Walter, only one other chronicler, Henry of Knighton – who more or less copied Walter’s account – mentions Margoth and Ralph of Ardern when describing the events at Kenilworth.

Six other accounts relaying the events leading up to the Battle of Evesham all refer to either spies or some act of deception, while seven others refer to the act of surprising Simon junior’s forces, without mentioning any espionage or act of deception. All 13 accounts were written between 1265 and the early 15th century.

This absence of other mentions of Margoth might lead us to doubt Walter’s account. But we know he drew on eyewitness sources for some parts of his chronicle – for example, canons who fled to his priory at Gisborough (North Yorkshire) from Scotland in 1297 were his source for the unfolding story of violence there. And the fact that other accounts of the 1265 incident mention spies, but using different words to describe them, suggests that the information came from a number of sources, giving it greater credence. One of them, a chronicle written at Melrose Abbey, also mentions a ‘traitorous knight’ – which may well refer to Ralph of Ardern too – in its description of the surprise at Kenilworth.

Medieval spies

The Latin terminology used by Walter to describe Margoth is important. Initially he calls her explorator, a (male) spy, but then refers to her as exploratrix, a (female) spy. This discrepancy is open to interpretation, but might best be read as Walter’s rhetorical strategy to surprise his readers – first mentioning a spy, and then that the spy is a woman dressed in men’s clothes.

The words explorator and exploratrix have often been translated as ‘spy’ – the word adopted, for example, by the late 13th-century chronicler Robert of Gloucester (writing in Middle English) when describing the surprise at Kenilworth. Beyond these specific events, however, contemporary writers use explorator or exploratrix in a wider sense, to mean scouts or agents. For example, Walenses exploratores, ‘Welsh scouts’, were employed by Sir Roger de Leybourne during violence in Essex following the siege of Kenilworth in 1266.

By its very nature, medieval espionage is difficult to detect. But fragments of evidence of both men and women spying do survive. In 1066, for example, King Harold sent exploratores across the Channel to spy on Duke William’s preparations for invasion; and in the early 13th century, English royal accounts show payments to Ralph de Chovin, ‘spy’ (explorator). Around 1209 a French exploratrix, Alice of Saintes, travelled to England in the service of King John to report her findings. And we know that dozens of women worked as messengers or spies in late 15th-century Belgium.

Medieval cross-dressing

How unusual was it for people to cross-dress in the medieval period? The best-known example is Joan of Arc wearing knightly armour in about 1430. But there are many other examples, found in a range of sources, from texts describing the lives of saints to court records.

The attitudes of religious authorities to cross-dressing were mixed. The Old Testament forbade it outright – ‘The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman’s garment; for all that do so are abomination unto the Lord thy God.’ However, the 13th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas took a more nuanced approach:

Hence it is itself sinful for a woman to wear man’s clothes, or vice versa; especially since this may be a cause of sensuous pleasure […]. Nevertheless this may be done sometimes without sin on account of some necessity, either in order to hide oneself from enemies, or through lack of other clothes, or for some similar motive.

On the whole, wider society’s attitudes to medieval women dressing as men seem to have been permissive if they had a religious or educational motive, or were doing so for their own safety. This was because, as Aquinas also argued, women were deemed inferior to men, so it was natural for them to aspire to a higher religious status – such as becoming a monk – or to protect themselves against ‘superior’ men.

In contrast, men who dressed as women were deemed to be violating a ‘natural’ law, by aspiring to a lower status. Some research suggests that male authors were perplexed by cross-dressing men, assuming that their sole motive was to gain sexual access to women.

There are many known examples of medieval women dressing as men for religious or practical reasons. Those dressing as men in order to enter monasteries include the 12th-century German monk Joseph of Schönau, who was revealed at death to have been born female. A number of instances have been found in London alone of women wearing men’s clothes for pragmatic reasons, such as Alice Street, who in 1495 dressed as a man to travel to Rochester. This was probably because a woman travelling alone on the road might have received unwelcome attention.

Despite the attitudes of religious authorities that cross-dressing was only permissible in certain circumstances, modern historians have been able to find several examples across Europe which confound these rules. For example, Wojciech of Poznan lived as a man and a woman in mid-16th-century Poland, maintaining romantic and sexual liaisons with both sexes. In 1493 a London resident, Thomasina, retained a female ‘concubine’ in men’s clothes in her room. A case of 1537 records that Agnes Hopton also dressed for an extended period as a man, in order to live with a married man.

One complex example from medieval England is the 1395 court case concerning Eleanor Rykener. Rykener was born John and, in the eyes of the authorities, was a man. Rykener appeared in court in women’s clothes, identified herself as Eleanor, and spoke of the support she had received in living as a woman from two other women. Though Rykener’s case is complicated – and its meanings much debated by historians – it provides a rare chance to hear the voice of a medieval cross-dressing individual.

The spectrum of experiences of cross-dressing may therefore range from the goal-specific and one-off episodes to what today might be described as ‘passing’ as the chosen gender. Whatever reasons people may have had, it’s likely that many other examples of medieval cross-dressing simply went unrecorded. Those records we do have – usually court proceedings – by their very nature provide only a filtered view.

Margoth’s cross-dressing

Bringing these examples together, how does Margoth’s cross-dressing fit into the spectrum of cross-dressing experiences in medieval Europe? Is it possible that Margoth dressed as a man, not for necessity or practical reasons, but as a matter of personal choice – or even both?

At first glance it might seem obvious that as a spy, Margoth would choose to dress as a man, both to pass unnoticed and for her own protection. However, some evidence suggests that an unknown man at or near a medieval army encampment might have been more likely to arouse suspicion than a woman. Many women unknown to the army are likely to have been present, whether selling food and drink, offering washing and basic healthcare, or as sex workers.

On the other hand are examples, like that of Alice Street, of women wearing male clothes to avoid suspicious eyes. Male clothing may simply have better suited Margoth’s task as Lord Edward’s spy, or to avoid her being confused with a sex worker – we know that sometimes women were chased out of camps or prevented from following the army.

Beyond this, it’s impossible to say whether Margoth’s cross-dressing went beyond a one-off episode. Historians today sometimes use the term ‘queer-like’ to give scope for reviewing and contextualising evidence that could suggest historical queer lives that may have been previously overlooked or sanitised. A ‘queer-like’ interpretation of Margoth might be that her cross-dressing experience – presumably accompanied by behaviour that echoed her masculine clothing, to help evade capture – may not have been confined to the functional or socially acceptable norms of the time.

Whatever Margoth’s reasons were, Walter’s brief reference to her is special on two counts. First, it provides a rare glimpse of a cross-dressing individual outside the legal records; and second, it is focused on that individual’s accomplishments, rather than on cross-dressing itself.

The rediscovery of Margoth

Later generations have represented Margoth’s experiences in a variety of ways. William Dugdale, writing about Kenilworth in 1656, follows Walter of Guisborough’s account in describing ‘a woman called Margoth, that cunningly travailed in mans apparell’. In 1844, William Blaauw’s study of the Second Barons’ War also drew on sources like Walter, recording Margoth as ‘employed as a spy in male disguise’.

But others, despite relying on Walter (and Henry of Knighton, who copied him verbatim), mention Margoth but without referring to cross-dressing. So in 1795, William Tindal omitted that Margoth dressed in men’s clothes but asserted that she was Ralph of Ardern’s lover. Similarly 80 years later an Evesham cleric delivered a lecture on the history of the area, in which he called Margoth a spy, but without mentioning her cross-dressing.

In 1939 Margoth was also reinvented for a pageant at Kenilworth Castle. Pageants were large-scale drama festivals, popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that encouraged communities across towns and villages to connect with their local history and identity. The 1939 pageant marked the first theatricalisation of Margoth’s role in the events at Kenilworth. On 13 July 1939 the Banbury Guardian’s report of the scene re-enacting the episode at Kenilworth in 1265 described Margoth as a ‘treacherous girl’ who, while Simon junior and his comrades were bathing in the castle’s lake, went to inform Edward of their absence. Edward later rides off ‘romantically’ with Margoth.

These changing portrayals of Margoth to some extent echo the challenges of understanding her medieval experience today.

Remembering Margoth

Margoth is only attested fleetingly, and the fact that she ‘went in men’s clothes as a man’ was a noteworthy but secondary detail as far as Walter of Guisborough was concerned. The tantalising glimpse he provides of a cross-dressing individual 750 years ago raises more questions than answers. We can only speculate about Margoth’s reasons for cross-dressing, in the light of what we know of other people at the time. But the existence of cross-dressing individuals in the Middle Ages perhaps challenges our assumptions about medieval people and shows us that some were prepared to cross boundaries and defy conventions.

Without question, however, Margoth’s success as a spy working for the future King of England is a testament to her skill and bravery. She is a rare example of a cross-dressing individual from medieval England who is recorded outside condemnatory legal records, and whose professional skill is celebrated first and foremost.

Find out more

-

Plan your visit to Kenilworth Castle

Scale the heights of the tower built to impress Eliizabeth I, marvel at the mighty Norman keep, and explore the recreated Elizabethan garden.

-

The Siege of Kenilworth Castle

Find out how Henry III’s assault on Kenilworth Castle, which began on 25 June 1266, turned into one of the longest sieges in English medieval history.

-

WOMEN IN HISTORY

Read about the remarkable lives of some of the women who have left their mark on society and shaped our way of life – from Anglo-Saxon times to the 20th century.

-

LGBTQ+ History

LGBTQ+ history has often been hidden from view. Find out more about the lives of some LGBTQ+ individuals and their place in the stories of English Heritage sites.

Further reading

Jenny Benham, ‘“A little bird told me …”: spies and espionage in the Norman world’, in Anglo-Norman Studies, 46 (2023), ed SD Church, 185–202

Judith M Bennett and Shannon McSheffrey, ‘Early, erotic and alien: women dressed as men in late medieval London’, History Workshop Journal, 77 (2014), 1–25 (subscription required; accessed 11 June 2025)

Vern L Bullough, ‘Cross dressing and gender role change in the Middle Ages’, in Handbook of Medieval Sexuality, ed Vern L Bullough and James A Brundage (New York: Garland Publishing, 1996), 223–42 (accessed 18 June 2025)

Anne Curry, ‘Sex and the soldier in Lancastrian Normandy, 1415–1450’, Reading Medieval Studies, 14 (1988), 17–45 (accessed 11 June 2025)

Jelle Haemers, ‘Women and war: female spies and messengers in the late-medieval Low Countries’, Journal of Women’s History, 36:2 (2024), 10–29 (subscription required; accessed 11 June 2025)

Valerie R Hotchkiss, Clothes Make the Man: Female Cross Dressing in Medieval Europe (London, 1996)

Megan Khoury, ‘Where do we go from here: transitivity and journey narratives in Eleanor Rykener’, in Medieval Mobilities: Gendered Bodies, Spaces, and Movements, ed BA Price et al (Basingstoke, 2022), 27–47

Tess Wingard, ‘The trans Middle Ages: incorporating transgender and intersex studies into the history of medieval sexuality’, English Historical Review, 138: 593 (2023), 933–51 (subscription required; accessed 11 June 2025)

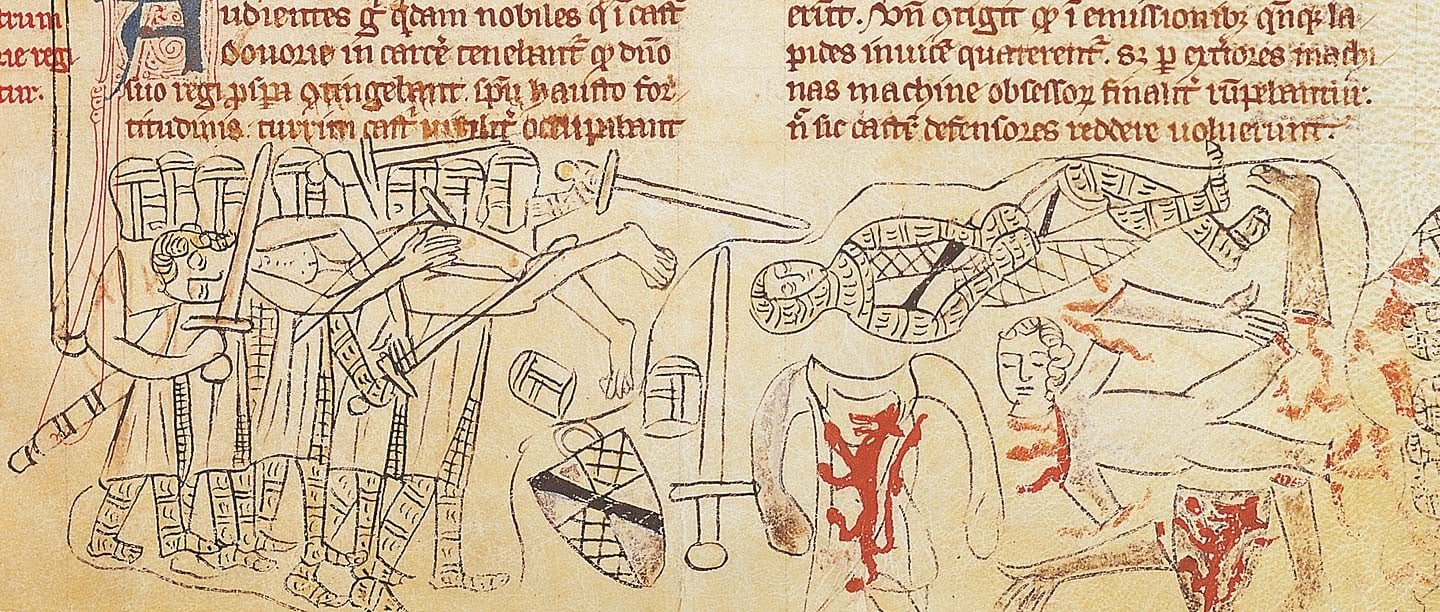

Top image: The Battle of Evesham and the death of Simon de Montfort, depicted in an early 14th-century manuscript. Courtesy British Library (Cotton Nero D.II fol 177)

The extract from Walter of Guisborough’s Chronicle is from an early 16th-century copy (image courtesy of The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, under a Creative Commons Licence)