Whirlwinds and Dragons

The first few months of the year 793 were worrying times. Later Anglo-Saxon writers in northern England recalled how ‘immense whirlwinds, flashes of lightning and fiery dragons were seen flying in the air’. They thought these aerial phenomena were portents of imminent disaster.

Sure enough, a great famine followed. But worse was to come. On 8 June,

heathen men came and miserably destroyed God’s church on Lindisfarne, with plunder and slaughter.

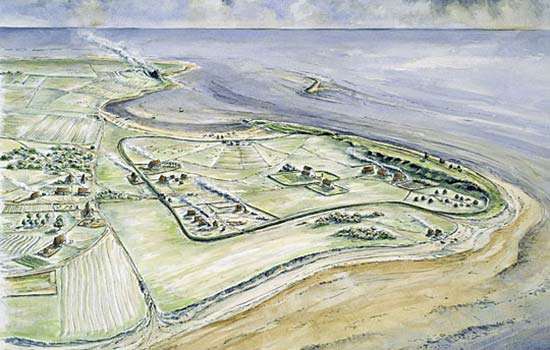

Holy Island

This Viking raid on the island of Lindisfarne, just off the Northumbrian coast, was not the first in England. A few years before, in 789, ‘three ships of northmen’ had landed on the coast of Wessex, and killed the king’s reeve who had been sent to bring the strangers to the West Saxon court.

But the assault on Lindisfarne was different because it attacked the sacred heart of the Northumbrian kingdom, desecrating ‘the very place where the Christian religion began in our nation’. It was where Cuthbert (d. 687) had been bishop, and where his body was now revered as that of a saint.

News of the raid quickly reached Alcuin, a Northumbrian scholar living far away in the Frankish kingdom, where he was tutor to the children of the renowned King Charlemagne. Alcuin was aghast at this unprecedented atrocity. As he wrote to Higbald, bishop of Lindisfarne, ‘a place more sacred than any in Britain’:

The church of St Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God, stripped of all its furnishing, exposed to the plundering of pagans.

A Vengeful God?

Alcuin was particularly worried about why God ‘and so great a company of saints’ had allowed this most holy of places to suffer.

He advised Higbald to examine his conscience to see if there was any reason why God might have allowed such a terrible disaster to happen. ‘Is this the outcome of the sins of those who live there?’ he asked. ‘It has not happened by chance, but is the sign of some great guilt.’ He wondered, too, whether the ransacking of a Christian church by non-believers world lead to ‘greater suffering’. Was Alcuin perhaps implying that he thought he knew why God’s wrath had been visited upon Northumbria?

The Anglo-Saxon chroniclers suggest that he did perhaps have recent sordid events in mind. On 23 September 788, the nobleman Sicga had led a group of conspirators who murdered King Ælfwald of Northumbria. Another chronicle records that in February 793 Sicga had ‘perished by his own hand’. But on 23 April his body was carried to the island of Lindisfarne for burial.

So a man who was both a regicide and had committed suicide had been buried there just six weeks before the Viking pirates struck. Was this the ‘great guilt’ Alcuin referred to? Clearly he thought that the pagan raids were an act of holy vengeance on a sinful people.

‘Greater Suffering’

Whatever it was that had brought about the raid on Lindisfarne, it was certainly only the beginning of ‘greater suffering’. Viking raids increased in frequency around the coast of Britain, Ireland and Francia. By 850 foreign armies were overwintering in England, and by 870 the Danish conquest of the northern, midland and eastern Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had begun.

But despite the ferocity of the attack at Lindisfarne, a Christian community survived there. The cult of St Cuthbert became the greatest in the North, moving first to Norham, then in 883 to Chester-le-Street, and thence to Durham in 995.

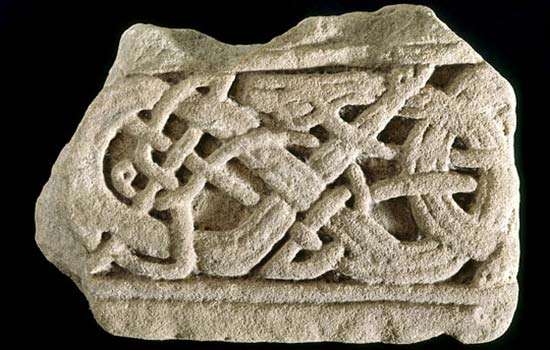

Christian continuity at Lindisfarne is shown by the religious sculpture made there in the 9th and 10th centuries. This includes the Domesday stone, which vividly depicts on one side a troop of seven uniformed warriors brandishing Viking-style battle-axes and swords. On the other side is a symbolic depiction of Domesday, when – so Christians believe – Christ comes again to sit in judgement on the sins of men.

By Joanna Story

Find out more

-

History of Lindisfarne Priory

Lindisfarne – also known as Holy Island – is one of the most important centres of early English Christianity. Read a full history of Lindisfarne Priory.

-

St Hild of Whitby

Hild is a significant figure in the history of English Christianity. As the abbess of Whitby, she led one of the most important religious centres in the Anglo-Saxon world.

-

Lindisfarne Priory Collection Highlights

Learn about the collection from Lindisfarne Priory, which includes internationally significant Anglo-Saxon stonework.

-

Description of Lindisfarne Priory

Find out more about the ruins of the 12th-century priory church and associated monastic buildings at Lindisfarne.

-

Significance of Lindisfarne Priory

Lindisfarne was one of the most important places in Anglo-Saxon England, while the post-Conquest church is a miniature version of Durham Cathedral.

-

Buy the Guidebook

The guidebook contains a beautifully illustrated tour and history, complete with full-colour maps, plans, eyewitness accounts and historic images.

-

Research on Lindisfarne Priory

Read a summary of research on Lindisfarne, which has focused on the Anglo-Saxon monastery’s history and on the surviving early sculpture and manuscripts.

-

Sources for Lindisfarne Priory

Read a summary of the main sources of information for our knowledge and understanding of Lindisfarne Priory.