Early years

The place name is derived from the Cornish Ros tor moyl, meaning ‘bare hilltop spur’. There is no detailed evidence for Restormel Castle before the 13th century, but a castle was almost certainly founded on this site in the 12th, if not the 11th, century.

In the 1930s the archaeologist Ralegh Radford suggested that Baldwin fitz Turstan, son of the sheriff of Cornwall at the time of the Domesday survey (1086), may have established the first castle.[1] It overlooked a ford across the river Fowey and so would have been of some strategic importance.

If the castle did not already exist by the 1140s, it may have been established at that time, like others in Cornwall, during the ‘Anarchy’ (civil war) of King Stephen’s reign.

Later evidence shows that from the mid 12th century the land on which the castle stands belonged to the Cardinham family, who were powerful landowners in central Cornwall.[2] Penhallam Manor, some 30 miles north, is another residence developed by the family.

Fragments of the inner gate tower survive from this early phase of the castle. Three pits and the well, cut into the bedrock in the courtyard, may be of similar date.

Restormel and the earls of Cornwall

The castle’s history from the mid 13th century onwards is better known. The king’s brother-in-law Simon de Montfort briefly owned it from July 1265 during the unrest of Henry III’s reign, but it reverted to its former lordship on his death in battle later that year.

In 1268 the Cardinhams’ heiress, Isolda de Tracy, granted to Richard, Earl of Cornwall and King of the Romans, the town of Lostwithiel – a fishery on the river Fowey – and the castle of Restormel,[3] complementing his castles at Launceston and Tintagel. In 1270 he acquired a fourth castle at Trematon.

Earl Richard died in 1272, only four years after acquiring Restormel, so it seems more probable that it was his son Edmund who built the present castle. Edmund’s work at Trematon Castle is documented and provides a parallel.[4]

Restormel’s buildings cannot be dated more precisely. However, a grant issued there in 1293[5] and surviving accounts of 1296–7 suggest that the main construction was already finished by then. Other features established by this time included a spacious hunting park, a garden and at least two hermitages (where hermits lived).[6]

Significantly, Earl Edmund transferred his Cornish capital from Launceston to Lostwithiel, probably in the 1280s. This is the most context for the rebuilding of Restormel Castle, only a mile away.

Earl Edmund died without an heir in 1300.[7] The Earldom of Cornwall then became vacant until Edward II elevated Piers Gaveston, his favourite, to the title in 1307. Gaveston was executed by the king’s opponents in 1312, but slightly later documents suggest that he had allowed the castles of Cornwall to fall into disrepair.[8] Occasional documents of the 1320s and early 1330s refer to repairs being needed at Restormel and other castles.

The Black Prince

In March 1337 Edward III made his son Edward (later known as the Black Prince) Duke of Cornwall, and endowed him with a huge estate. This included the properties formerly belonging to the Earldom of Cornwall.[9]

A comprehensive survey of this estate, known as the ‘Caption of Seisin’, was made in summer 1337. This documents the prince’s acquisition of his new properties and provides the most detailed description of Restormel Castle in its history.[10]

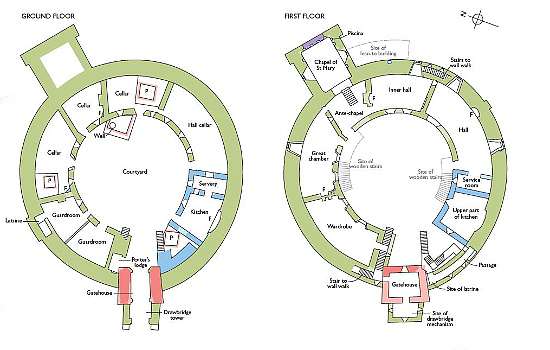

It records an inner ward or enclosure (which survives today) containing a hall and three chambers over cellars, a chapel, and a stable for six horses, the last perhaps in the courtyard. There is no mention of a kitchen.

The survey also describes a larger outer enclosure (now lost) with a great hall and a further three chambers, all above cellars, together with a chapel, service buildings, and stabling for 20 horses. A lead conduit supplied water to the castle. Many of the buildings were already decaying at this time.

The first years of the Duchy of Cornwall were a high point in the castle’s history. The Black Prince issued many writs for its repair and operation, and also for improvements to the park.[11] Medieval accounts show that more money was spent on maintaining the park boundary than on any other feature at Restormel – a reflection of the high value placed on hunting.

The castle’s closeness to Lostwithiel, a key site for the administration of the Stannaries – the regional organisations regulating the tin industry – gave it considerable economic importance. For example, in 1346 the Black Prince ordered that one of the only two licensed pewterers working in the Duchy was to be based at Restormel.[12]

The prince stayed at the castle in August–September 1354 and again in the winter of 1362–3, when he celebrated Christmas there.[13] These are the only known occasions on which a member of the royal family lived at the castle. Perhaps a beautiful medieval Venetian glass beaker, found in fragments in the castle ditch in 1880, was brought there during one of these visits.

The Later Middle Ages

Restormel Castle was sporadically repaired under Richard II in the later 14th century,[14] and in the mid 15th century under Henry VI[15] and Edward IV.[16] The accounts of repairs made under Edward IV also give details of works to other buildings in the park. Among them was the hermitage chapel of the Trinity, almost certainly on the site of either the later Restormel Manor or Restormel Farm, below the castle.[17]

In the mid 1460s repairs were carried out to ‘The Lodge’, a complex of timber and stone buildings including a hall and two chambers. This may have been the same as the outer ward of the castle, or it may have stood in another part of the park.[18]

Lostwithiel’s fortunes were uncertain, however, partly because of the silting up of the river Fowey with waste from tin-streaming on Bodmin Moor. As the town became difficult for seagoing ships to reach, Restormel Castle likewise declined.

Decline and Civil War

There were Cornish uprisings against English royal government in 1497, 1548 and 1549, but there is no evidence that Restormel Castle saw action at the time. By the 1540s, only its inner ward was habitable, the outer enclosure being ‘sore defaced’.[19] At some point before 1542 Henry VIII converted the royal park at Restormel to open countryside, reportedly transferring the property to Sir Richard Pollard, one of his officials.[20]

After this no repairs were made to the castle. In 1584 the cartographer John Norden described a scene of desolation. In the outer ward, only the remains of a huge oven could be detected, while plundering of the inner ward’s buildings for lead, stone and timber had begun.[21] Richard Carew’s description of 1603 suggests that some materials had been sold rather than stolen.[22]

During the Civil War the castle was briefly garrisoned for the last time. In summer 1644 a Parliamentarian army under Lord Essex took it over. It seems likely that only part of the derelict castle was pressed into service as a gun emplacement – probably the chapel which overlooks the valley, and perhaps the gatehouse.

Much of Cornwall strongly supported the royalist cause, however. On 21 August the royalist Sir Richard Grenville captured Restormel for Charles I, finding a garrison of 30 men there. Days later, Essex’s army surrendered, leaving Cornwall under royalist control.[23] After the eventual victory of the Parliamentarians, the castle was so ruinous that surveyors considered it ‘not worth the taking down’.[24]

Abandonment and decay

This was the last time Restormel functioned as a castle. Afterwards it was to become known as a historical curiosity and a feature in the landscape. From the 1620s onwards 16th-century Restormel Manor (known until 1774 as Trinity House, on the site of the medieval hermitage of the Trinity) was leased and remodelled.[25]

The manor’s 18th-century occupants added a plantation of trees across the castle’s former outer enclosure, framing the ivy-clad ruins in a ‘picturesque’ fashion. The castle itself became something of a tourist attraction, visited by, among others, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, in 1846.[26]

By 1920, however, the condition of its stonework was giving cause for concern, after years of apparent neglect and uncontrolled vegetation. The Office of Works negotiated with the Duchy of Cornwall over repairs, and finally agreed to take the ruins and the site of the outer ward into state guardianship. The transfer took place on 6 March 1925.[27]

The ruins were cleared of vegetation and rubble, and the masonry conserved or, in parts, reconstructed. The castle was prepared for public viewing by the addition of timber stairs and balustrades, and by the felling of an avenue of conifers in 1941.[28] Since 1984, the site has been managed by English Heritage.

About the author

Jeremy Ashbee is the Head Historic Properties Curator at English Heritage. He specialises in the study of medieval palaces and castles.

Find out more

-

Visit Restormel Castle

At Restormel today you can explore the castle buildings, enjoy panoramic views from the wall-walk and take a stroll through the tranquil grounds.

-

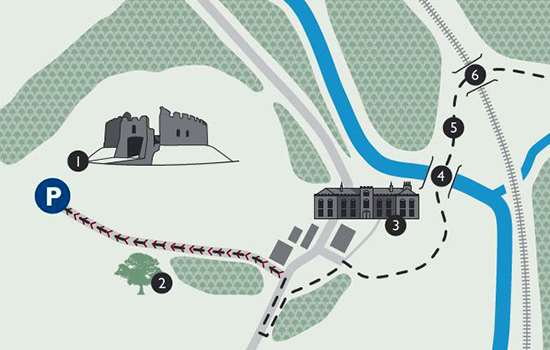

Restormel walking trail

Download this trail before your visit to guide you on a meander through the beautiful Fowey valley linking the castle with the Duchy of Cornwall Nursery.

-

Description of Restormel Castle

Read a description of the castle, where the main rooms are ingeniously fitted within an almost perfectly circular plan.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan to discover how the castle buildings developed over time.

-

Earl Richard of Cornwall, King Arthur and Tintagel Castle

Discover why the legend of King Arthur led Earl Richard, owner of Restormel Castle, to build a castle on an inhospitable rock at Tintagel.

-

Visit Tintagel Castle

Built half on the mainland and half on a jagged headland, Tintagel Castle is one of the most spectacular historic sites in Britain.

-

Visit Launceston Castle

Like Restormel, Launceston was one of the four Cornish castles of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and was begun soon after the Norman Conquest.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.