A circular castle

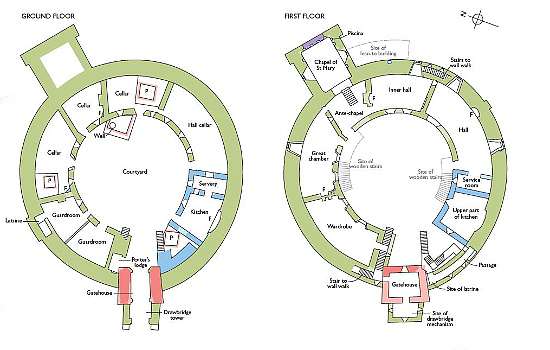

The standing ruin of Restormel Castle, formerly the castle’s inner ward or enclosure, is highly distinctive. It takes the form of a low curtain wall enclosing buildings ranged around a central courtyard. Its plan is almost perfectly circular – only one other circular castle is known in England in the Middle Ages.[1]

Its design is a variant of the type called a ‘shell keep’. However, Restormel is unusual for its spacious size (33.3 metres in diameter), its situation – not on a high motte (mound) but partly buried by an earth bank within a deep ring-ditch – and its late date. This building type is generally associated with the 12th century rather than the late 13th.

Interior

The stonework of the inner ward is mostly courses of slate-stone rubble with plentiful evidence of putlog holes (for the scaffolding poles used during building). Many dressed stone features have been lost, but surviving elements include fragments of three cross-shaped arrowloops in the curtain wall, traces of window seats and doors, and numerous corbels (supports for the roof timbers). A shallow pointed arch in the inner gatehouse is in fine stone from Pentewan, about 10 miles away.

The courtyard was surrounded by a range of buildings. They were two-storeyed, except for the kitchen. This lay to the south of the gatehouse and was open through two storeys with a wide fireplace in its outer wall.

The levels of first floors can be reconstructed from sockets and ledges in the outer and inner walls and in the radial walls dividing the rooms from one another. The range’s inner wall is fragmentary at first-floor level and some parts are entirely missing, but the positions of most windows and doors remain visible.

Moving anticlockwise from the kitchen, the main first-floor rooms were a hall; an inner hall or solar; the ante-chapel; and then two further rooms, thought to be the great chamber and a wardrobe, or storeroom. The hall, ante-chapel and great chamber could be entered directly from wooden stairs rising from the courtyard.

All the first-floor rooms communicated directly with adjoining spaces apart from the wardrobe at the north-west corner. This was accessible only by a stone stair against its gable wall.

The ground-floor spaces were all unheated and most were probably storerooms.

The outer wall is especially well preserved, with surviving window openings under shallow pointed arches, fireplace positions and a battlemented wall-walk. Some of the radial walls are built against it, such as those of the kitchen, but several are bonded with it. This shows that the outer wall and most of the buildings within it were constructed during a single operation.

Exterior

Viewed from outside, the curtain wall runs round the circuit with two projecting structures – the gatehouse to the west and the chapel to the east.

A stone plinth, visible just above the top of the earth bank, probably marks the original line of the ground. This lies close to the first-floor level inside the castle, so that the external bank conceals the ground floor inside.

Three large windows provide views southwards down the valley towards Lostwithiel, but there is only one window facing north. A shallow projection on the north side covers a latrine chamber. On the south side, a rough area indicates where the stack of the great hall chimney was removed.

No traces of the outer ward (enclosure) can now be seen. The area is planted with trees, a vestige of a designed landscape created by the owners of Restormel Manor in the 18th century.

Gatehouse and chapel

The gatehouse was built in two phases. The inner part, pre-dating the rest of the present buildings, mostly survives as low walls flanking the carriageway, but it evidently once had three storeys.

More survives of a two-storeyed outer tower, with an upper window and battlements. The stone bridge replaces a medieval drawbridge.

The chapel is entered through a wide arch from the ante-chapel. It probably sits above a solid masonry base, although there are tales of a hidden crypt in which two skeletons were found.[2]

As well as the piscina (a basin for washing holy vessels) and blocked niches to north and south, the chapel retains evidence for a large window in its east wall. At some point in or before the 17th century the window’s openings were blocked and its tracery replaced by a heavy wooden structure, giving support to cannon mounted on the chapel roof.

Earlier features

Inside the castle are four square stone-lined pits, which all probably pre-date the present buildings. One, on the eastern side, gives access to the well, and the south wall of the ante-chapel runs at an odd angle to avoid it. The other three are mysterious, but may mark the positions of three towers of an early castle. If so, there are parallels at nearby Launceston Castle.[3]

Find out more

-

History of Restormel Castle

Read a history of this 13th-century castle, from its foundation as a luxurious residence and hunting place to the present day.

-

Earl Richard of Cornwall, King Arthur and Tintagel Castle

Discover why the legend of King Arthur led Earl Richard, owner of Restormel Castle, to build a castle on an inhospitable rock at Tintagel.

-

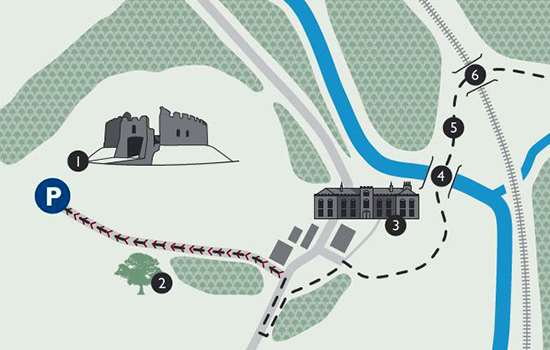

Restormel walking trail

Download this trail before your visit to guide you on a meander through the beautiful Fowey valley linking the castle with the Duchy of Cornwall Nursery.

-

Download a plan

Download this PDF plan to discover how the castle buildings developed over time.

-

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

-

Visit Restormel Castle

At Restormel today you can explore the castle buildings, enjoy panoramic views from the wall-walk and take a stroll through the tranquil grounds.

-

Visit Launceston Castle

Like Restormel, Launceston was one of the four Cornish castles of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and was begun soon after the Norman Conquest.

-

Visit Tintagel Castle

Built half on the mainland and half on a jagged headland, Tintagel Castle is one of the most spectacular historic sites in Britain.