Building the gate

The building of the gate was the work of local company Town Carpentry, led by Matt Town. In this short film, Matt explains how they tried to use the same techniques as the Romans, and the challenges of undertaking a project in the middle of a historic site.

You can also watch a timelapse sequence of the gate being built.

The Roman invasion and Richborough

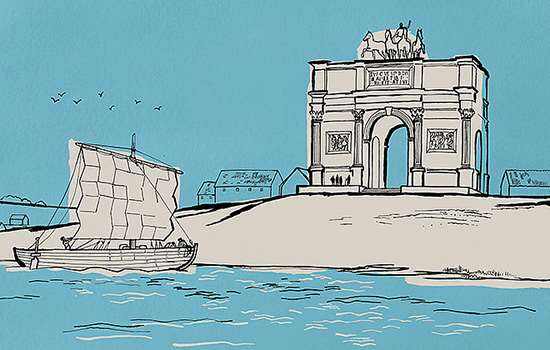

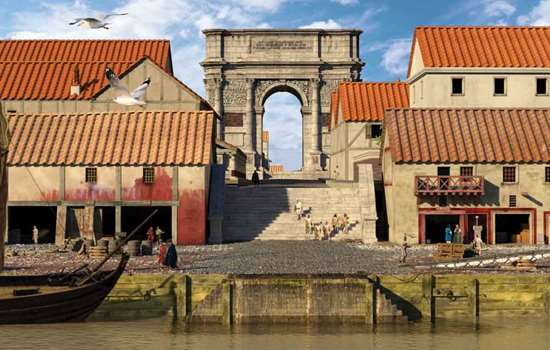

In AD 43, on the orders of the Emperor Claudius (reigned AD 41–54), a Roman army of about 40,000 soldiers crossed the English Channel to begin a war of conquest. The most likely place for the landing of this army is the east Kent coast, centred on Richborough. In the Roman period Richborough was a small island at the southern end of a channel between the mainland and Thanet, which was then an island.

Between 1923 and 1932, archaeologists excavating at Richborough pieced together evidence for a Roman fortification there, dating from the time of Claudius. The fortification was unusual. It had two closely set, parallel ditches that were later shown to extend in a straight line for about 650 metres, before bending eastward at the southern end. The northern end had been lost. There was only one gap in their lines – a causeway of undisturbed ground, forming an entrance.

These ditches probably protected a strip of land on the east side of the island, where ships could be beached, and troops and supplies landed.

The original gateway

The causeway carried a road surfaced with a thin layer of pebbles. Immediately behind the eastern ditch, the archaeologists found six post holes flanking the road. These suggest that the route through the entrance was flanked by six timber posts, three on each side. The posts, each about 0.3 metres square, would have been set in the packed turf and sand lining the deep holes.

These posts would have formed the principal structural uprights of a timber gatehouse, with an entrance passage 3.4 metres wide. The gatehouse would have been set within a defensive earthen bank or rampart, of which no trace remains. The fortification defended the shoreline behind it to the east.

Why recreate the gate?

The idea of building a Roman-style gatehouse began to take shape in the early stages of planning a re-presentation of Richborough. However, to build a new structure on a site in state guardianship, protected by law, required extensive consultation, Scheduled Monument Consent and planning permission. That complex and detailed process meant we needed a compelling case for making such a major change to an internationally important historic site.

We had two principal reasons for attempting it. The first was to highlight how important Richborough was, as the probable landing place of the Roman army in AD 43. For a site that witnessed the beginning of Roman Britain, the physical evidence of that period was underwhelming. It comprised the sections of the ditches left exposed after the 1920s excavations, and a small earth bank created at that time to represent the rampart. Apart from this not reflecting the historic arrangement, the surrounding features from later periods overshadowed it. Recreating the gateway would better reflect the Claudian period fort at Richborough.

The second reason related to Richborough’s archaeological complexity. This partly results from the fact that the site was occupied throughout and beyond the Roman period. But mostly the complexity reflects the way Richborough’s remains have been displayed since the 1920s excavations. Visitors are confronted with a bewildering array of walls, restored ditches, exposed footings of excavated buildings, and concrete markers representing lost buildings.

Viewed from ground level, this jumble of features from different periods can be hard to untangle. But if visitors could look down on them from a height, their understanding would be considerably enhanced. Recreating the Claudian gateway would achieve this.

Doing no harm

We also needed to be sure that our proposal would not damage Richborough’s buried archaeology or spoil its character. The site of the gateway and rampart had been fully excavated in the 1920s, and all that survived from the Roman period were features cut into the underlying geology. Our guiding principle was to confirm where such features survived and to design foundations which did not affect them. In other words, whatever we built could in theory be removed and allow archaeologists to re-examine the surviving evidence beneath it.

So far as character was concerned, the site bounded by the walls of the later fort is large and open. We developed detailed visualisations to test the effect recreating the gateway would have on the setting of the wider monument. Although the gateway would be impressively large, standing 8 metres tall, it would sit comfortably in the north-west corner of the later fort without being an overwhelming presence. And because the site is already presented as a mixture of exposed and restored features of different periods, a newly recreated element would sit far more harmoniously than it would have in a well-preserved historic setting.

But was there enough evidence to recreate the gateway? And how could we be sure that visitors would encounter something which reflected its original form and appearance? What follows shows how we answered those questions.

Appearance

Early in 2020 we asked Historic England archaeologists to re-excavate the site to test the details revealed during the earlier excavations. In a small trench, the team located five of the six post holes (the position of the sixth was just beyond the trench area) in the positions recorded in the 1920s. They also found the remains of the road surface. This confirmed the ground plan of the gatehouse.

Roman earth and timber fortifications have been much studied. In Britain, the army built most of them between AD 43 and about AD 150. The many fort gatehouses that have been excavated follow varied but repeating ground plans.

For the three-dimensional appearance of such gates, however, we need other source material. The spectacular Trajan’s Column in Rome is a mine of evidence for the Roman army. Its sculptured frieze depicts scenes from the Emperor Trajan’s military campaigns in Dacia (modern Romania) in AD 101–2 and 105–6. These include many ramparts and gatehouses, in enough detail for us to recreate their appearance.

The column shows gateways with open, box-like timber towers, often rising to two storeys over a gate passage. The first storey links the rampart walks on either side, while the second, immediately above it, provides an elevated open platform for observation and defence.

Using these sources, together with knowledge gained in previous Roman-style gatehouse constructions – notably the Lunt fort, near Coventry, and at Fagl Ln, near Wrexham – we created a design for the Richborough gatehouse with the help of architects Donald Insall Associates.

Wood and carpentry

Roman carpenters used similar hand tools to those in use today – adze and axe, saws, chisels, planes and files, as well as drill bits in a bow drill. So the finish on woodwork could be very accomplished. Evidence from Roman buildings in Britain where wood survives has revealed a well-developed and widespread wood-framed building tradition. Timber joints were made with care to fit tightly, using many types including lap, scarf, mortice and tenon, lap dovetail and dovetail. At The Lunt fort, all of these joint types were used in the construction.

The gate passage at Richborough was wide enough to have needed two gates, hinged at their outer edges and opening inwards. Most Roman gates pivoted on the vertical timber forming the outer edge of the gate frame. These timbers had strong tenons at top and bottom – often with iron collars – that fitted into mortices in the timber lintel and sill of the gate opening. The mortices were sometimes also lined with iron and lubricated, along with the tenons, so that the gates turned easily.

Each gate needed a strong, jointed timber frame, braced on the rear face, with a single layer of vertical boards nailed to the outer face. One such gate, found at Vindolanda, just south of Hadrian’s Wall, measured 3.66 metres tall and 1.37 metres wide. Horizontal wooden locking beams that extended across the width of both gates were probably used to make the gates stronger and more secure when closed. These would have fitted into U-shaped iron brackets on the inside face of the gate leaves.

Recreating the rampart

A Roman-style gatehouse would look very strange without a rampart, especially when short lengths of the twin ditches are visible. So we have created a short length of rampart on either side of the gatehouse.

Although the 1920s excavations found no trace of a rampart, it was probably used to infill the ditches when the fort was no longer needed. However, archaeology and descriptions by Roman authors give us an idea of their general form. Methods of construction varied. In a rampart built of stacked turves, earth and timber, the front face needed to slope between 65 and 75 degrees from the horizontal to form an effective barrier, while the rear face could be a gentler 45 degrees. That is the basis of our rampart. It has been built to today’s standards using modern materials to ensure the rampart is extremely stable because of the steep slope to its west face. But it has been made to look like its Roman ancestors.

The timber parapet on top of the rampart is formed as a frame of uprights connected to rails, to which vertical planks are nailed edge-to-edge. Wattle hurdles would be a reasonable alternative, but planks should last longer. The boards forming the parapet face and the floors of the gate tower are between 0.2 and 0.45 metres wide, the range found on preserved Roman wooden structures excavated in London. They are fixed using hand-made iron nails of Roman types, with large flat heads, square sections and shanks tapering to a point.

The build

Sourcing and preparing the timber, cutting it to size, jointing and assembling were the responsibility of Town Carpentry, led by Matt Town. The tower is mainly of oak, seasoned for at least 15 years to reduce moisture content, so that cracking and splitting, through drying out, can be kept to a minimum.

Matt had been involved in building the Fagl Ln gatehouse, so had carried out his own research on the historical and practical aspects of building a Roman gatehouse. That experience enabled him to offer many positive suggestions that contributed to the design of the gatehouse, including the strongest and most appropriate joint types for different parts of the structure.

Working off site, Matt’s team cut each timber element to size, made the joints and tested them. They then transported the timbers to Richborough and assembled them in framed sections, which were lifted into place by a crane.

With hardly a hitch, it all fitted together perfectly – a testament to the care in preparation and craftsmanship.

Find out more

-

VISIT RICHBOROUGH ROMAN FORT AND AMPHITHEATRE

Richborough is perhaps the most symbolically important of all Roman sites in Britain, witnessing both the beginning and end of Roman rule.

-

HISTORY OF RICHBOROUGH ROMAN FORT AND AMPHITHEATRE

Read a full history of this key site, which witnessed over 360 years of Roman rule – the entire length of the Roman occupation of Britain.

-

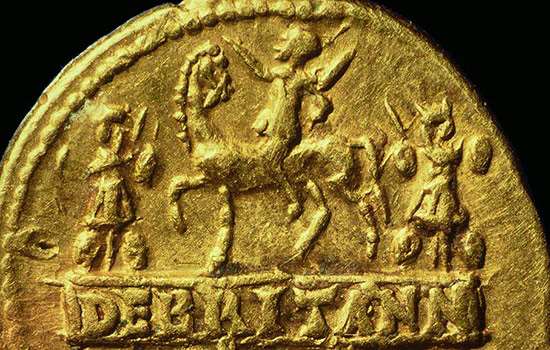

GATEWAY TO BRITANNIA: RICHBOROUGH’S ARCH

The story of Richborough’s monumental arch reveals the great importance of Richborough to the Romans as the gateway to Britannia.

-

THE RICHBOROUGH AMPHITHEATRE: DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION

Excavations of Richborough’s Roman amphitheatre in 2021 produced some revolutionary results. Find out what the archaeologists discovered.

-

THE MANY FACES OF RICHBOROUGH

See some of the remarkable faces – of gods, monsters, men, women and animals – from the objects on display in Richborough’s museum.

-

Richborough and the Roman World

Explore a map of the Roman Empire to find out where some of the objects found at Richborough came from, and how they got to Richborough.

-

ROMAN BRITAIN

Read an overview of the 400-year period when Britain was part of the Roman Empire, from AD 43 to the early 5th century.

-

THE ROMAN INVASION OF BRITAIN

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched an invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?