Prelude to invasion

During Julius Caesar’s military campaigns in Gaul between 58 and 50 BC, he mounted two expeditions to Britain. The first, in 55 BC, was simply an armed reconnaissance, but the second in 54 BC was a serious attack that subdued the major tribes in south-eastern Britain. The Romans didn’t stay, but several tribes may have become friendly ‘client states’, in some respects still independent but also subordinate to Rome.

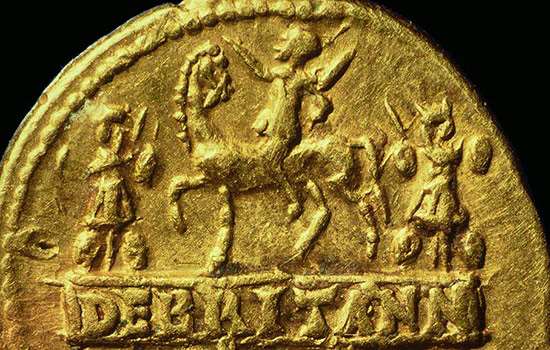

For almost a century afterwards, tribal rulers in southern Britain maintained diplomatic relations with Rome and traded across the English Channel with its provinces. However, during the first 40 years of the 1st century AD, the Catuvellauni tribe, based to the north and east of London, gradually gained power over neighbouring tribes, the Trinovantes and the Atrebates. This gave them control of territory further south, and also forced the expulsion from Britain in AD 42 of Verica, the pro-Roman king of the Atrebates.

The Catuvellauni’s growing anti-Roman stance coincided with the emperor Claudius’s desperate need to consolidate his fragile hold on power. The usual way for emperors to shore up support was by military victory. So, the invasion of Britain was planned, with the treatment of Verica and the Atrebates as the pretext. Claudius sent an army in AD 43.

Invasion and conquest

Landing at Richborough, the Roman army rapidly established control. By AD 47 it had a firm grip in the South and East, with a broad frontier zone heading north-east from Exeter to the Humber.

A rebellion in East Anglia by Boudica, queen of the Iceni, checked progress in AD 60. The Romans suppressed her attempt to reverse the subjugation of her tribe, but in the process the Iceni burned three Roman towns at Camulodunum (Colchester), Verulamium (St Albans) and Londinium (London) to the ground.

The Roman advance resumed around AD 70, when the conquest of Wales and northern England began. The Roman governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola advanced his army up into Scotland as far as Aberdeen on the east coast, and defeated Caledonian tribes in battle at Mons Graupius in AD 83.

Read more about the Roman invasionTwo great walls

The victory was short-lived, though. Troops were withdrawn to deal with trouble on the Danube frontier, and the army, struggling to hold the far north of Britannia, gradually fell back. By around AD 105 it had established a new border zone along an east–west road, the Stanegate, between the river Tyne in the east and the Solway Firth in the west. By this time there were permanent bases for three legions – heavily armed infantry units of 4,800 men, formed of Roman citizens – at Caerleon (in south Wales), Chester and York. Auxiliary troops – smaller regiments of infantry and cavalry, raised from non-citizens in the provinces – garrisoned a network of smaller forts, mostly across northern England.

It was just a little further north of the Stanegate that the emperor Hadrian, visiting Britain in AD 122, ordered the building of a wall to stretch from sea to sea, as a permanent frontier to Britannia. Hadrian’s Wall was mostly complete by AD 130. Within a short time, the emperor Antoninus Pius advanced north again, and from around AD 142 built another wall on the Forth–Clyde isthmus – the Antonine Wall. But this wall only had a short life, being gradually abandoned between AD 158 and AD 164.

There were later military campaigns in the far north, including a huge campaign by the emperor Septimius Severus in AD 208–11, penetrating beyond the Antonine Wall. But territory was not permanently conquered and Hadrian’s Wall remained the effective imperial frontier.

Romanisation

How much difference the Roman conquest made to everyday life varied from place to place. In the far West, Wales and most of the North, the army always remained at the forefront of daily life. Soldiers occupied a network of forts, connected by good roads, to police this huge area, in which Roman ways of life had far less impact than in the Midlands, South and East. In those areas, urban civilisation developed. Camulodunum was initially the province’s main town, though Londinium quickly replaced it.

There was never a massive influx of ‘Romans’. The people living in Britannia across the period of Roman rule were mostly the descendants of the pre-Roman tribes, and they lived and worked mainly in the countryside. There was a veneer of Roman officials, while the troops were originally recruited from provinces across the empire.

There would have been a gradual merging of people and culture in and around towns and forts, but in the countryside perhaps less so. The population was probably between 3 and 4 million, of which the army comprised up to 50,000.

Town and countryside

The Roman economy in Britain was focused on towns, where a new urban governing class was created, composed of the former tribal rulers and their descendants. The province was divided into large administrative areas, or civitates, based on the tribal territories. Each of these had a capital, for instance at Silchester, St Albans, Aldborough and Wroxeter.

These towns were planned and built along Roman lines. Their ruling councils promoted a Roman lifestyle, erected typical Roman buildings, and governed the towns as centres of trade, manufacture, distribution and taxation. Between around AD 70 and the later 2nd century, such towns generally grew and prospered.

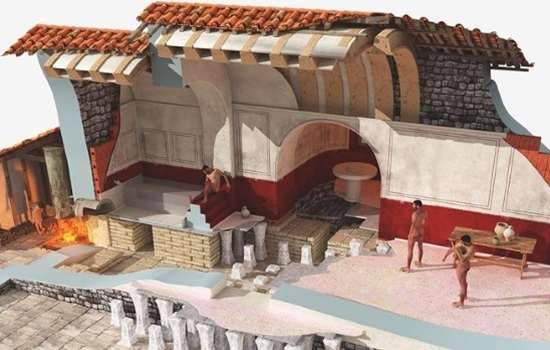

In between the civitas capitals, along the roads and at road junctions, were smaller towns, roadside settlements and industrial centres. Many of them grew more organically and lacked most of the typical Roman public buildings, though many – like Wall, Staffordshire – had a mansio, an official guesthouse that provided accommodation and fresh means of travel for the imperial postal network. In the North and West, where settlement remained military, settlements outside forts sometimes grew to the size of small towns, but generally lacked urban trappings and sophistication.

The countryside remained as it had been before, filled with farms, but now they were linked by tracks and lanes to the major roads, and their produce could be sold in the towns. Such farms were sometimes rebuilt and reorganised, while villas – Roman-style buildings of varying size – were a new feature of the countryside. The most elaborate had underfloor heating, bath-houses, mosaics and elaborately painted walls, and formed the centres of large rural estates. It was often members and descendants of the former tribal elites who lived in them.

In the far North, where few villas were built, traditional farmsteads remained numerous and fitted into the intense Roman system of supply and taxation.

Throughout the province, life outside the main settlements was slow to change; people simply had new and more demanding masters. Most of the population were the rural poor who, together with slaves, did the bulk of the work. The Roman economy depended on slaves, but we don’t know whether those in Britain had come from elsewhere in the empire or were from the province itself.

Trade and industry

The Romans needed both to recoup the costs of conquest and to generate income – most importantly to pay for the army, the engine that kept the empire functioning. Consequently, soon after the conquest, administrators began to exploit the agricultural and mineral wealth of the new province. In the North and West, it was the fort garrisons that facilitated tax collection and the marshalling of natural resources, including the extraction of precious metals.

British grain was an important export to feed Roman armies abroad, while animals – mainly cattle, pig, sheep and chickens – also formed an important element in the economy. Minerals, particularly lead, silver, tin, copper and iron, were mined to produce all manner of everyday tools, weapons, trinkets and personal items. Pottery production centres multiplied, while a new tradition of building in stone boosted large-scale quarrying and the production of brick and tile. Salt production boomed. Glass-making flourished, while other natural products such as jet were worked into jewellery and amulets.

All this and more formed part of a money-based economy, centred on the towns, which included the large-scale import of both everyday and luxury items from elsewhere in the empire.

Religious tolerance

Although the Romans brought their official gods and goddesses, they were not at all prescriptive in religion. Indeed, soldiers from all over the empire brought their own deities and eastern mystery cults to Britannia, such as Mithraism.

These imported religions went hand in hand with indigenous deities, and where characteristics were shared, hybrid gods emerged. The worship of Sulis Minerva at Bath – where the goddess Minerva was identified with the local god Sul – is a prime example. Worship took place in the towns and the countryside, at cult centres, small temples and open-air shrines.

In AD 313 the emperor Constantine I recognised Christianity, which had previously been outlawed, as a legitimate religion. Christianity then became more widely adopted across the empire, including in Britain.

A changing province

In AD 196–7 the governor of Britain, Clodius Albinus, led a serious but unsuccessful revolt against the emperor Septimius Severus. In the aftermath, Britannia was divided into two provinces, Britannia Superior and Britannia Inferior, each with its own administration and capital, with the clear intent of dispersing power.

In the century that followed, the Roman Empire endured a long period of turmoil, beset by raids and incursions of tribes from beyond the frontiers, and endemic civil warfare. Britain was part of two breakaway mini-empires, each of which lasted for a decade or more – the Gallic Empire (AD 260–74) and the empire of Carausius and Allectus (AD 286–96). The emperor Constantius restored the British provinces to the Roman Empire in AD 296, and when he died in AD 306 after a campaign against the Picts in Scotland, his son Constantine the Great was proclaimed emperor in York.

The turbulent years of the 3rd century were reflected in Britain in a slowdown in civic building and the enclosing of civitas capitals and smaller towns with defensive walls. The first regular raids on the province by Saxons from north-west Europe may have begun in the early 3rd century, when new forts were built on important estuaries on the east coast, for example at Brancaster, Caister-on-Sea and Reculver, though Roman writers do not record raiding at this time.

By the early 4th century, the administration of the empire had become even more systematic in raising taxes to support the army in order to defend the frontiers and overcome civil wars. Under the emperor Diocletian (AD 284–305), Britain was divided into four provinces, each with its coterie of officials to ensure efficient tax collection.

The army in Britain was also reformed in the face of growing threats. The Picts had emerged as a formidable enemy north of Hadrian’s Wall, and raiders from Ireland plagued the western coasts, while seaborne Saxon raiders were an increasing menace in the South. The army of Britain was dispersed as smaller units in both forts and towns for defence in depth: these became centres for tax gathering as well as places of military storage and supply.

The so-called Saxon Shore probably emerged as a discrete military command around the south-east coast, probably sometime in the early 4th century. It used forts most likely to have been built during the breakaway reigns of Carausius and Allectus, at Richborough, Dover, Burgh Castle, Lympne, Pevensey and Portchester.

The end of Roman rule

The early 4th century saw a return to some peace and prosperity. Parts of the West and South West witnessed a flurry of palatial villas built, while others, such as Lullingstone and North Leigh, were extended.

But towns were not what they had been at their height in the 2nd century. Persistent trouble on Rome’s other frontiers, and relentless taxation in Britain, ensured that towns operated on a more practical basis, and began slowly to decline. With only a few exceptions, civic buildings were neglected, reused for other purposes or abandoned. Resources were now squarely directed into state needs – the army – and there was little left over to express civic pride. War in the AD 350s in Persia and Germany resulted in the withdrawal of troops from Britain, while vast quantities of grain were exported to feed the army abroad.

There was also trouble on the Hadrian’s Wall frontier from around AD 360. It culminated in widespread raiding by Saxons, Picts and other groups – sometimes referred to as the Great Conspiracy of AD 367 – when much of the province was in turmoil.

Under the emperor Valentinian (r.AD 364–75), Hadrian’s Wall and other garrisons were strengthened. But despite this, confident new building had ceased in Britain by the AD 370s. Subject to neglect by Roman emperors, generals based in Britain repeatedly attempted to usurp power – including Magnus Maximus in AD 383–8, and Constantine III in AD 407–11 – and Britain was drained of its best troops.

By AD 411, formally separated from Roman imperial administration, without an army and lacking organised taxation, the provinces of Britain could not sustain themselves, and town life totally collapsed. Thereafter, the inhabitants of Britain were no longer part of Rome, and had to find ways of fending for themselves.

By Paul Pattison

More about Roman Britain

-

The Roman invasion of Britain

In AD 43 Emperor Claudius launched his invasion of Britain. Why did the Romans invade, where did they land, and how did their campaign progress?

-

Roman Bathing

Read about Roman bathing – an essential part of Roman life – and discover what Roman bath-houses reveal about the culture and people of the time.

-

Emperor Hadrian

Learn about the man behind Hadrian’s Wall, the most impressive statement of his policy of securing the empire’s existing borders.

-

Roman Coastal Defences and the Saxon Shore

Discover what we know about the Roman forts built along the coast of east and south-east England in the 3rd century AD.

-

Roads in Roman Britain

Discover how, where and why a vast network of roads was built over the length and breadth of Roman Britain.

-

The Romans in the Lake District

Find out about the network of forts and roads the Romans built in the Lake District to control this area on the empire’s frontier.

-

Country Estates in Roman Britain

An introduction to the design, development and purpose of Roman country villas, and the lifestyles of their owners.

-

From across the Empire

Explore a map of the Roman Empire to find out where some of the objects found at Richborough Roman Fort in Kent came from.