Cast in the spotlight

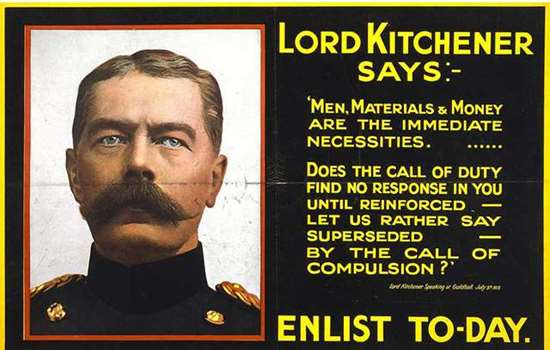

In January 1916, at the height of the First World War, the British government passed the Military Service Act, introducing conscription for the first time. It made military service compulsory for millions of men across Britain, but also included a ‘conscience clause’, allowing men to object on moral grounds. About 20,000 men registered as COs during the following two years.

As a result, these men were cast in the spotlight and were much discussed, particularly in the press.

Find out more about Conscription and exemption

Popular images of conscientious Objectors

Representations of COs in the media were overwhelmingly negative. The derogatory term ‘conchie’ became the typical name for a man who appealed against his conscription. In newspapers COs were branded as lazy men who ‘shirked’ their duties. Sometimes they were portrayed as the enemy and branded as traitors, or alternatively as cowards who were too afraid to fight. In an atmosphere of popular support for the war, and propaganda that celebrated those who had volunteered to fight as heroes, the CO was seen to have betrayed his country.

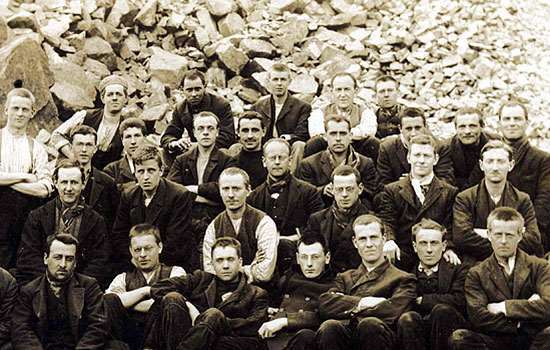

Furthermore, the men who refused to fight were shown in the press as unhealthy and physically weak. In contrast to the immaculately uniformed soldiers, COs were often portrayed as dressing shabbily, which suggested that they were incapable of looking after themselves. Rather than fulfilling the stereotype of the soldier hero, non-combatants could be depicted as blundering fools, incapable of being ‘real men’.

Gender Bending

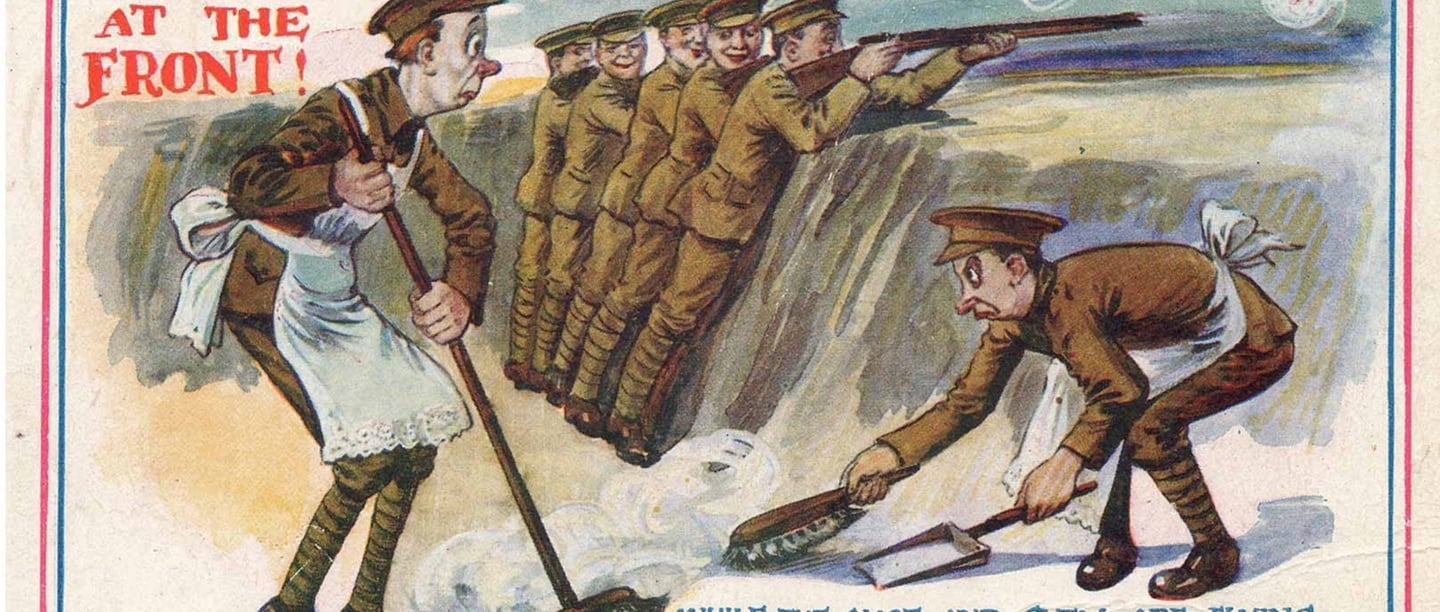

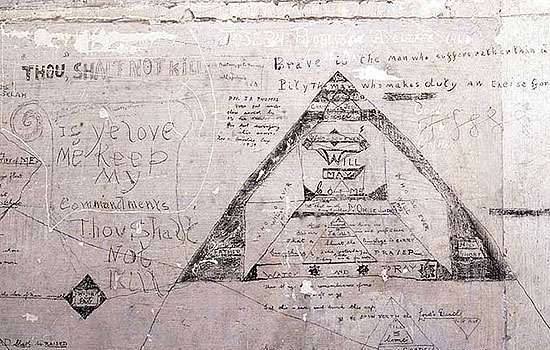

COs were therefore also seen to be bending gender norms. The press often called them ‘sissies’ or ‘pansies’. Cartoons and postcards pictured them wearing dresses or performing traditional female chores. In one postcard (above) COs are shown wearing women’s aprons and sweeping trenches while other soldiers sneer at them. Some men were accused of homosexuality (then illegal) and depicted acting in camp fashion.

Such depictions aimed to undermine and humiliate the non-combatants. The ridicule extended to propaganda posters, literature and popular song, such as Alfred Lester’s famous ‘The Conscientious Objector’s Lament’.

While individual COs’ experiences differed, popular culture was overwhelming hostile. When Bert Brocklesby, one of the Richmond Sixteen in prison for refusing to take part in the war effort, was released in April 1919, he noted the annoyance of those who were still waiting for their boys in the army to be demobbed: ‘Why should skunks and skirkers get free before men who have been fighting for their country?’

Read individual COs’ storiesAfter the war

After the war, however, perceptions of COs did slowly begin to change. By the time of the Second World War, conscientious objection had become much more acceptable. During that conflict over 60,000 men across Britain applied to be COs, almost four times more than in 1916. On the whole, the COs of the Second World War came under less scrutiny in the media than they had previously. Attacks on the ‘Home Front’ demanded the creation of a strong Civil Defence in Britain throughout the conflict, which in turn created the opportunity for many thousands of COs to serve in non-combatant roles that were highly respected.

The decision to become a CO was still not easy, however. Three thousand COs were still sent to prison during the conflict, and accusations that COs were cowards, shirkers, or Nazis were not uncommon. Despite this, throughout the rest of the 20th century resistance to war became an increasingly accepted stance.

Conscientious Objection Today

Since 1945 the stories of COs and other war resisters have become an integral part of our wider narratives of the First World War. Particularly during the centenary of that conflict, many projects have been launched that explore this element of the war.

It has become increasingly clear that while First World War COs were strongly criticised and ridiculed in the media, attitudes towards them in local communities were much more ambiguous, and in places supportive. While representations of attitudes to COs in the press were overwhelmingly negative, the reality of attitudes was actually more complex.

Charlotte Tomlinson, University of Leeds