Defence against invasion

St Mawes Castle is a four-storey artillery fort, like its counterpart, Pendennis, across the bay, and was built in the 1540s as part of the largest national coastal defence programme since the Roman era. It stands solidly above the rocky coast, once a deterrent to hostile ships that might have sought to venture up the river.

Against the backdrop of Henry’s break with Rome, England found itself politically isolated. Following a French and Spanish alliance in 1538, and the possibility of an attack on England, the king looked to fortify the south and east coasts. The Fal estuary was one of several locations where the enemy might gain a foothold in England.

We know that in 1537 an important local dignitary, John Arundell, had already petitioned the king to protect the Fal with ‘blockhouses made upon our haven’. But he had to wait until 1539 and after, when St Mawes was begun as one of 30 new fortifications built by Henry VIII to defend important ports and anchorages around the coast. This flurry of building became pertinent half a century later when the Spanish Armada sailed close by. The area continued to be a vulnerable and therefore fortified until after the Second World War.

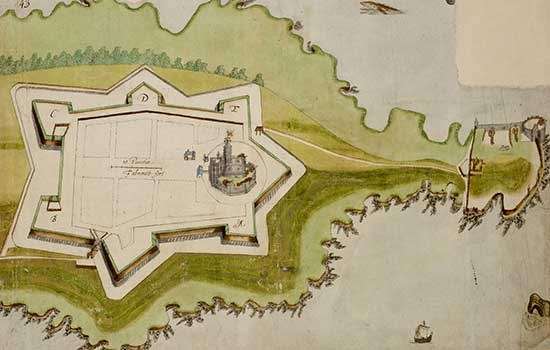

Two castles to guard

The building programme ensured that the Carrick Roads was guarded by the two main castles of Pendennis and St Mawes, developed to create crossfires across the anchorage. Two smaller blockhouses offered further protection, their guns positioned to fire from the shoreline.

Although visitors to the castles today will find them varying in scale, their size and armaments were comparable in their original incarnations. Both fortifications remained in military use from 1540 until 1956, and the size and complexity that we see at Pendennis Castle today dates from its expansion in 1597–1600 and thereafter.

Wars at St Mawes

The tensions between England and Spain continued in the 1560s and beyond. Periodically the castle’s small garrison increased, including during times of crisis such as 1574 when word came of the gathering of a hostile fleet at a Spanish port.

The Spanish threat was to continue, with war formally declared in 1585 and lasting until 1604. In 1588, the Spanish Armada caused high alert but ultimately sailed past. However, Cornwall was raided by a small Spanish force in 1595 (at Penzance, Newlyn, Mousehole and Paul). In 1596 and 1597 another Spanish Armada set sail for England, with its target Carrick Roads, but was foiled by bad weather.

In 1779 militia were called up during the American War, when another French invasion was expected, and remained on alert at the castle until 1783. St Mawes was again garrisoned between 1793 and 1815 during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, with ten heavy guns (24-pounders) placed outside the castle on a battery close to the shore in preparation for conflict.

St Mawes arms for new warfare

A period of relative peace followed 1815, with a lull in activity at the castle. Some 40 years later, though, a looming French naval threat was the impetus for dramatic change – a complete rebuild of the shore battery at St Mawes. The Grand Sea Battery for 8-inch guns, with an accompanying magazine (ammunition store), was completed and ready for action by the mid 1850s.

The significance of the thriving commercial port of Falmouth was acknowledged in the 1880s, and accordingly identified as vulnerable to enemy attack. The 8-inch guns of 30 years before were replaced by 64-pounder rifled guns, and these were supplemented in the 1890s by up-to-date quick-firing 6-pounder guns and machine guns to counter the threat of fast torpedo boats.

The Second World War

After a lapse in active use the castle was garrisoned again in the Second World War, which brought a flurry of preparations. This included the addition of twin 6-pounder guns built on the shoreline north-west of the castle. These fearsome weapons could launch a hail of shells at a very fast rate of fire against approaching torpedo boats and small warships.

The castle saw especially high alert throughout the spring and summer of 1944, when American troops and equipment arrived for training before D-Day and the invasion of the Normandy beaches. It is easy to imagine the thrum of activity these new arrivals would have brought, with the castle once again buzzing in preparation for conflict.

Castle life

What was it like to inhabit this fascinating structure? The castle garrison was normally small – no more than 15 people – and sometimes reduced to just a master gunner. It would have been fully manned by well-trained militia and volunteers in emergencies.

The area has seen remarkable change over the centuries. When St Mawes was built, Cornwall was remote from central government and used its own language. The government pursued its policies through local commissioners and gentlemen who were able to apply strong local influence. At St Mawes this was initially Thomas Treffry, a rich merchant from Fowey.

Those who lived and worked in the castle in its first 150 years were mainly local, and loyal to their captains. They probably served part-time, with soldiering and gunnery not their only occupations. This was likely to have changed during the Commonwealth period (1649–60) and for a while thereafter, when professional soldiers may have been in garrison.

During the 18th century a system of care-and-maintenance under a master gunner and a couple of assistants was adopted, while militia and volunteers trained to use the castle guns on a part-time basis were brought in during emergencies.

Henry’s vision preserved

In 1956, no longer needed because rockets had replaced coast artillery, St Mawes Castle passed to the care of the state in recognition of its exceptional historical importance. Few Henrician artillery forts are so complete and so able to tell the tale of Henry’s vision.

Visitors can still see carvings invoking the castle’s originator:

Semper vivet anima Regis Henrici Octavi qui anno 34 sui regni hoc fecit fieri (May the soul of King Henry VIII, who had this [castle] built in the 34th year of his reign, live forever).

Explore Further

-

History and Stories of Pendennis Castle

Explore the range of stories associated with the imposing, larger castle across the bay from St Mawes - Pendennis Castle.

-

Tudor Warfare

The Tudor period saw the gradual evolution of England’s medieval army into a larger, firearm-wielding force supported by powerful ships and formidable gun forts.

-

Buy The Guidebook

The guide covers both Pendennis and St Mawes castles and includes rich histories, detailed reconstruction drawings and maps.

Visit other Henrician Castles

-

Visit St Mawes Castle

St Mawes Castle, perched across the bay from Pendennis Castle, offers a stunning counterpoint to its larger sibling.

-

Visit Portland Castle

Portland Castle, in Dorset, features concrete D-Day fortifications as well as a 1540's Henrician fort.

-

Visit St Catherine's Castle

This beautiful Cornish castle is free to visit and small but perfectly formed, with a single two storey tower.