The Battle of the Solent

The immediate stimulus for building Yarmouth Castle was fighting in 1545 between England and France – part of the larger Italian War of 1542–6 in which Henry VIII was allied with the Holy Roman Emperor against the French. Henry VIII’s navy engaged a huge French fleet in the eastern Solent heading for Portsmouth – the occasion when the Mary Rose sank. At the same time, three forces of French soldiers landed on the eastern side of the Isle of Wight, where some bloody skirmishes occurred with English troops.

Though the fighting at sea and on land was brief and inconclusive, the need for better fortifications on the Isle of Wight was clear. Work resumed on an incomplete fort at Sandown immediately and began on another, at Yarmouth, in 1546.

Improvements to the island’s defences were entrusted to the Captain of the Isle of Wight, Richard Worsley, with building at Yarmouth overseen by George Mills. In 1548, Mills’s account was settled, but the castle was not completed. Nevertheless, by 1552 it was garrisoned by a captain, Richard Udall, a porter and 17 soldiers. It was equipped with 12 heavy guns, 19 handguns and a store of 140 longbows and 223 bills (a two-handed slashing and stabbing weapon) – enough to supply the local part-time soldiery when required.

On the other side of the Western Yar river, the Tudor builders constructed Sharpenode bulwark in 1545–7. An earthwork fortification equipped with 22 guns, it helped Hurst Castle to control the Needles Passage into the Solent, and also worked with Yarmouth Castle to defend the Western Yar.

The design of the castle

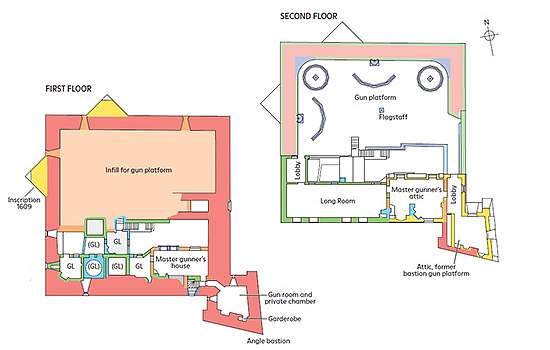

The builders of Yarmouth Castle chose to fortify a location next to the town quay, to dominate the landing point on the river. The castle was formed as a square enclosure with a high curtain wall, washed by the sea on two sides. On the landward sides it was defended by an angle bastion (an artillery platform) and a wet moat.

Behind the parapet of the curtain wall, a platform for heavy guns was open to the elements. In the original plan, two floors of buildings were intended underneath it, ranged around a central square courtyard, with openings for more guns in the curtain wall of the first-floor rooms. This arrangement was not completed when building ceased in 1548. However, within 20 years, building resumed and the castle was completed to a major new design.

The angle bastion

The castle at Yarmouth is the earliest surviving English experiment with a new style of fortification.

Most of Henry’s artillery forts, built from 1539 onwards, used a circular design with a central tower surrounded by rounded bastions. These forts – including for example Deal, Walmer and Calshot – supported a large number of guns to generate massive offensive firepower. However, defensively the circular design left blind spots at the base of the bastion walls, which an attacking force could exploit.

An Italian innovation, the angle bastion – which projected outwards from the walls of a fortification – addressed these weaknesses. The one at Yarmouth was placed at the south-eastern corner. Typically it is shaped like an arrowhead, with four straight sides joined at angular corners. Two longer sides, or faces, mounted guns to fire upon an approaching enemy, while two shorter ones, the flanks, contained guns to fire along the walls on the landward side of the castle.

With this arrangement, an enemy could not get close without being exposed to defensive fire.

Move the sliding bar to compare an illustration (left) of the intended design of Yarmouth Castle (c.1547) with how we think the castle was completed by 1565 (right). The buildings around a central courtyard shown in the design were either never built or remained unfinished. By 1565 the central courtyard had been filled in, with another created along the south side of the castle, while a large gun platform occupied over two-thirds of the castle area. © Historic England/English Heritage Trust (illustration by Bob Marshall and Carlos Lemos)

Late Tudor and early Stuart alterations

In the early years of the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603), radical alterations were made to Yarmouth Castle: in 1559–65, the castle was completed to a modified design by infilling the northern half of the courtyard to create a large gun platform, whose gunfire was concentrated towards the sea.

This left a narrow courtyard in the southern half, with access from the original entrance, in the castle’s eastern wall, to a single range of buildings. This south range provided some accommodation – probably for the captain, porter and master gunner, with the soldiers and gunners perhaps billeted in the town – and storage. The castle survives in this redesigned form today, though altered in some details.

In 1597–8 an earth bulwark, containing more heavy guns, was made outside the castle on the east side, and workmen made further repairs in the castle between 1599 and 1603. In 1609 two large triangular buttresses were added to the exterior wall, and the gun platform and parapet were raised to their present heights, blocking the original Tudor gun openings. A third storey was added to the south range.

Further works in 1632 included new vaulted rooms on the ground floor, to allow for the garrison gunners to live in. The Long Room was built over them as a large store room (and later a barracks) and there were new structures over the courtyard, supported by large arches.

The garrison’s fortunes

Henry VIII’s castles were intended to house small garrisons that would be reinforced in times of war. But the intended 20-man complement at Yarmouth was not maintained and later garrisons were usually smaller. Exceptions occurred during the Civil Wars (1642–51), when 30 men garrisoned the castle for Parliament, and during the First Dutch War (1652–4), when numbers rose to 70.

All of them were withdrawn in 1661 during a programme of reduction in military spending following the Restoration of Charles II (r.1660–85), when the king’s government suggested that the Yarmouth town authorities should pay for their own garrison.

No action was taken until 1668, when the veteran admiral Sir Robert Holmes bought the governorship of the Isle of Wight. He re-established a garrison of four gunners at Yarmouth Castle and brought guns from Cowes. In 1679 he acquired land adjacent to the castle, where he demolished the eastern external bulwark and filled in the moat. He then built a fine private house and garden, and had a new entrance made in the south wall of the castle, as the original one now intruded onto the garden.

A new battery for heavy guns was established on the quay, looking along the west wall of the castle directly out to sea.

Yarmouth in later years

In the last years of the 17th century and for much of the 18th, the castle fulfilled its roles in coast defence and securing the passage to and from the mainland. The garrison was always small: in 1725 a master gunner and two gunners looked after 18 heavy guns in the castle and on the quay battery (twelve 18-pounders and six 6-pounders). The house in the south range became known as the Master Gunner’s House.

By 1741 the guns had been replaced by five 9-pounders and eight 5¼-pounders, and by 1805 there were four 9-pounders and eight 6-pounders. The main guns stood on the castle platform. Probably in the early 1850s, the number of guns was reduced to four, placed on traversing carriages that allowed easy movement. The steel rails on which the carriage wheels turned can still be seen today, along with a 24-pounder gun (c.1805–20) with a replica traversing carriage of mid-19th-century type.

For most of the 18th century, a master gunner and five gunners formed the garrison. All of them were resident. Even after the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, when the castle was of little use, a master gunner maintained the guns, probably into the 1850s.

A review of the castle in 1859 revealed that it had been assigned as barrack accommodation for one officer and 21 infantrymen, probably for local militia or volunteers, though it was not used at the time. The quay battery had been removed and a coastguard station had been established next to the castle.

In the 1880s, the army allowed civilian use of the castle, as the eastern Solent was comprehensively protected by huge forts at Hurst Castle, Fort Albert, Fort Victoria and the Needles Battery. The castle was taken back for military use in both world wars of the 20th century, but since 1984 it has been in the care of English Heritage.

By Paul Pattison

Find out more

-

Visit Yarmouth Castle

Henry VIII’s last and most advanced coastal fort

-

Download a plan

Download this pdf plan of Yarmouth Castle to see how the castle buildings developed over time.

-

Isle of Wight Travel Guide

Discover why Queen Victoria described the Isle of Wight as her ‘paradise’ – and perhaps even make it your own.

-

MORE HISTORIES

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.