Stonehenge and its European Connections

How archaeology has revealed Stonehenge’s place at the centre of wide-reaching prehistoric networks of trade, exchange and ritual – both national and international.

WELL-CONNECTED

Stonehenge lies at the heart of a stretch of quintessentially English chalk downland. But at several periods in prehistory it was also at the centre of a wide range of networks that stretched across north-west Europe and beyond.

Even as early as the Mesolithic period (8000–4000 BC) the hunter-gatherers occupying the Avon valley and the surrounding downs were using tools of a type found at a number of sites in Sussex. One of these was made of stone from Wales – presaging the famous use of Welsh megaliths at the great monument itself.

BURIED TREASURE

The first construction at Stonehenge – of its surrounding ditch and banks, and a ring of large pits known as the Aubrey Holes – occurred in about 3000 BC. The stones that stood in these holes were soon removed and cremations were inserted instead, in the enclosure ditch and in shallow scoops within the site.

One of these burials was accompanied by a fine, highly polished macehead carved from banded gneiss (a common striped stone), probably of Breton origin. Elsewhere on the site stone axes from Cumbria and Cornwall have been found, as well as a piece of Niedermendig lava from northern Germany, over 400 miles east of Stonehenge – extraordinarily far away, considering the slowness and difficulty of long-distance travel at the time.

CONTINENTAL DESIGN

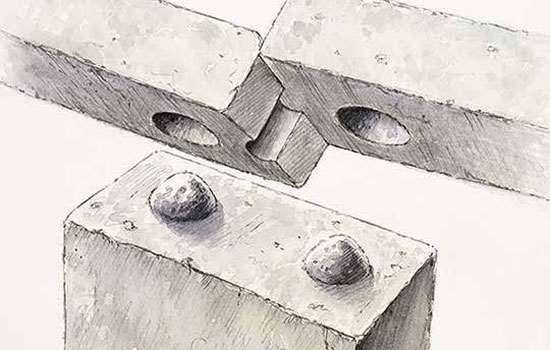

Five hundred years later the stone monument that we see today was constructed, using huge sarsen stones brought from neighbouring downs and smaller bluestones from the Preseli Hills of south-west Wales.

The stones were arranged on a plan that is unparalleled but has its closest relatives in Brittany. The people who erected them used a distinctive style of pottery that was developed in northern Scotland, but was also used at nearby Woodhenge, Marden (Hatfield Earthworks) and Avebury.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that these people, who also gathered at Durrington Walls for midwinter feasting, were consuming cattle that may have been grazed in the Scottish highlands.

FROM THE ALPS TO ASIA MINOR

From isotope analysis we now also know that a man buried close to Stonehenge, just across the river Avon, in about 2400 BC – the famous ‘Amesbury Archer’ – came from the Alps, most probably from what is now Switzerland. So although we no longer believe that Stonehenge was designed by an architect from the Mediterranean, as was once thought, people were unquestionably drawn to it from far away.

Another glory of the Stonehenge landscape is the dense cluster of early Bronze Age burial monuments (2200–1700 BC), such as the Cursus barrow group. Now grass-covered mounds, they conceal constructions that were built, altered, rebuilt and reused over many generations. The artefacts accompanying the burials within them reflect even more wide-ranging contacts: bronze daggers from northern France, pots from Brittany and a curious pronged bronze object that may have parallels in central Europe or as far away as Turkey.

Today, Stonehenge attracts visitors from all over the world. It seems that in its heyday it had almost as many impressive international connections.

By Mark Bowden

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.

More about Prehistoric England

-

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.