Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence – mainly bodies with fatal injuries – is often subject to varying interpretations. Where earlier archaeologists identified massacres, revisionists have put forward less sensational explanations.

ARROWS AND ARCHERS

Evidence is now emerging that the early Neolithic period of great communal tombs (4000–3500 BC) was not always an era of peaceful co-operation. Those whose bodies have been found at Belas Knap Long Barrow in Gloucestershire, Wayland's Smithy in Oxfordshire, and elsewhere were killed by blows to the head or arrow wounds. Hundreds of flint-headed arrows have been found at the causewayed enclosures of Crickley Hill, Gloucestershire, and Hambledon Hill, Dorset, where the attackers also burned the defensive palisades.

Bows were certainly used in conflict as well as for hunting. The Stonehenge Archer, himself identified as a bowman by his protective wrist-guard, was shot in the back by three arrows, and finished off at close range by another.

Though probably not the victim of violence, the roughly contemporary (about 2300 BC) Amesbury Archer was also buried with wrist-guards and fine flint arrowheads. His other grave goods, however, presaged the new metal-working technology which revolutionised weaponry.

Arms Race

The development of bronze weapons set off a prehistoric arms race. Bronze daggers evolved into longer ‘rapiers’ for thrusting, which were succeeded by heavier bronze slashing swords. Bronze-headed spears were used as javelins, or for close combat.

There may even have been regional fighting traditions, with swords used in the north, swords and spears in the south-east, and mainly spears in the south-west and midlands. We have little evidence for violence, however, and many of these items may have been for display.

HILLFORTS

During the Iron Age (from about 800 BC) iron weapons gradually superseded bronze. Ditched and ramparted earthwork hillforts also proliferated in the south and west. They are most numerous in Devon and Cornwall, where 285 survive, many of them small.

Much more spectacular are the often multi-ramparted hillforts of Hampshire, Wiltshire and Dorset, including Bratton Camp, Uffington Castle and Maiden Castle – the biggest hillfort in Europe – and the Welsh border counties, including Old Oswestry.

FORTRESSES OR SYMBOLS?

Hillforts were traditionally viewed as fortresses: instruments and indicators of widespread tribal warfare. The renowned archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler even attributed the addition of multiple ramparts to some forts to developing sling-shot technology. Certainly hoards of sling-stones have been found at Blackbury Camp, Devon, and some 20,000 carefully chosen beach pebbles were discovered near the elaborately defended entrance of Maiden Castle.

Despite the defensive character of such entrances, more recent archaeologists view hillforts primarily as displays of power, with multiple subsidiary roles, including occasional refuges, centres of commerce and animal pounds. Most had been abandoned before the Roman invasion of AD 43, so highly coloured accounts of the ‘last stands’ of British hillforts have also been discredited.

CHARIOTS

Greek and Roman commentators provide the first written descriptions of British war chariots. Julius Caesar was struck by the skilful way they were used in Britain when he invaded in 55 BC:

In chariot fighting the Britons begin by driving all over the field hurling javelins … then … they jump down from their chariots and engage on foot.

Meanwhile their charioteers waited nearby to rescue them if they were too hard-pressed.

Remains of late Iron Age two-horse chariots have been found in east Yorkshire (at least two accompanying burials of women), while a hoard of showy chariot-horse trappings was discovered near Stanwick Iron Age Fortifications, also in Yorkshire.

These remains are too flimsy to have been used for ‘chariot-charges’, but typify an individually heroic, ‘hit and run’ style of warfare which proved no match for the Romans.

More about Prehistoric England

-

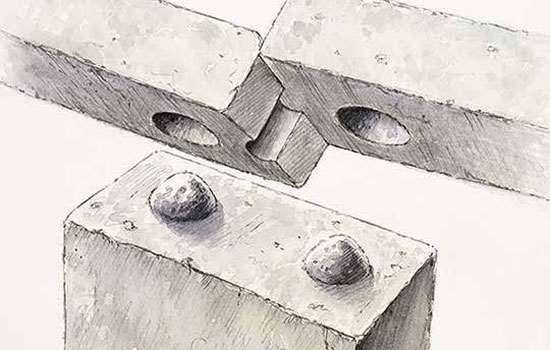

Prehistoric Architecture

The structures that survive from prehistory might not be what we’d normally think of as ‘architecture’. But these structures still inspire awe today

-

Prehistoric Art

People in prehistory were skilled at making tools and decorative objects from stone and metal, sometimes with astonishing decoration.

-

Prehistoric Commerce

Goods and skills must have been bartered or exchanged in prehistoric Britain from early times, but very little evidence has survived and commece as we think of it may not have existed.

-

Prehistoric Daily Life

The arrival of farming from about 4000 BC had a profound effect on every aspect of daily life for the people who lived in the British Isles.

-

Prehistory: Landscape

How Neolithic people linked complexes of person-made monuments into artificial landscapes.

-

Prehistory: Networks

The arrival of farming, the building of great communal monuments and the knowledge of metalworking all transformed prehistoric Britain.

-

Prehistory: Power and Politics

Power in prehistoric Britain was expressed symbolically, through the likes of mighty communal monuments, rich grave goods, and massive hillforts.

-

Prehistory: Religion

There was no single or continuously developed belief system in prehistoric Britain, but we can make informed guesses about what different prehistoric people believed.

-

Prehistory: Conflict

Violence and conflict undoubtedly occurred in prehistoric Britain, but the archaeological evidence is often subject to varying interpretations.

Prehistory Stories

-

Food and Feasting at Stonehenge

Find out what the people who built and used Stonehenge ate, how they cooked and served their food, and the cutting-edge science behind these discoveries.

-

Long Barrows and Broken Bones

What the atmospheric, evocative long barrows of the Cotswold Hills and Marlborough Downs reveal about burial practices and attitudes to death in the early Neolithic period.

-

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

-

Making Connections: Stonehenge in its Prehistoric World

At the time of Stonehenge, people connected with others and with the world around them by making and sharing objects. Explore the story of these connections.

-

Ritual Mysteries in a Prehistoric Flint Mine

What finds at Grime’s Graves in Norfolk reveal about the significance of mining, and the value of flint, to Neolithic communities.

-

Iron Age Kings and their Roman Connections

How burial goods from Essex provide tantalising glimpses of rich and powerful leaders in Iron Age Britain, and their strong links with the Roman world.

-

Roman Invasion at Maiden Castle

Britain’s largest Iron Age hillfort was once regarded as a monument to the brutality of Roman invasion, but its story may be rather more complicated.

-

Prehistoric Earthworks and Their Afterlife at Knowlton

How a unique group of Neolithic monuments in Dorset have remained a significant and atmospheric presence for 4,000 years.